The Rhinebeck Panorama: A game-changing view

The Rhinebeck Panorama is a pencil and watercolour drawing that provides an extraordinary bird's-eye view of London in 1806.

1806

One eye-widening, mind-expanding view

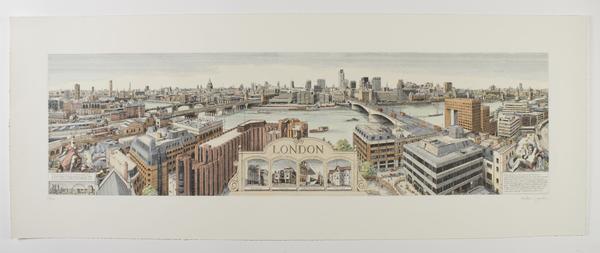

In an age of planes, drones and skyscrapers, it’s easy to make expansive aerial views of London. Of course, it wasn’t always like this. The desire to capture the whole city in one image has a long history, dating back to at least the 17th century.

The Rhinebeck Panorama, made around 1806, is an awesome, revolutionary example of that tradition – jaw-dropping in scale, but full of charming detail. For anyone seeing it then, it would have been an astounding new perspective on London, like taking a hot-air balloon flight over the city.

The image lay hidden for over a hundred years. Finally discovered in a barrel in the United States in 1941, it’s now part of our collection at London Museum.

Why the Rhinebeck Panorama is special

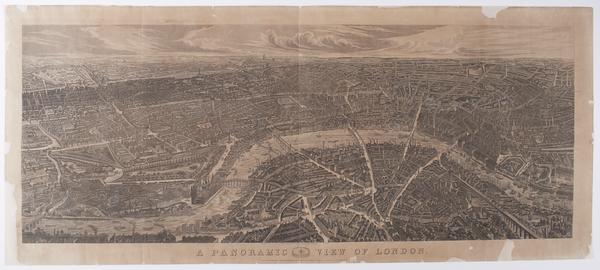

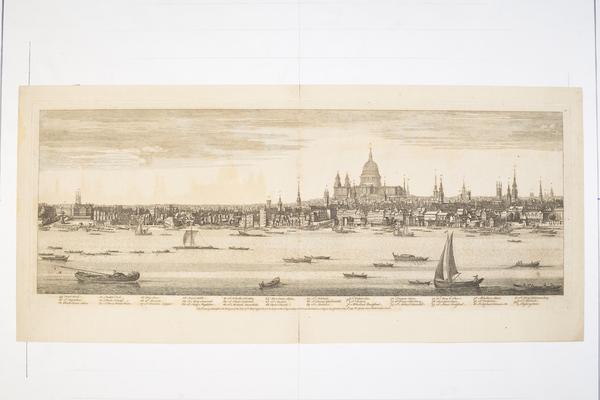

The earliest panorama of London in our collection is a view from Southwark in the 1630s. Many interesting panoramas followed in the next two centuries. But most used the same viewpoint, showing a flattened riverbank with Westminster and the City at either end.

The Rhinebeck Panorama changes all of this. A pencil and watercolour drawing on four sheets of paper, it provides an extraordinary bird's-eye view of London around 1806, from a point roughly where Tower Bridge now stands.

In this 180-degree view, we no longer look north but west. And we see London in its entirety.

“The effect is very astonishing. I actually put on my hat imagining myself to be in the open air”

Panoramas were all the rage

Towards the end of the 18th century, all-encompassing views became fashionable. Huge 360-degree paintings began to be exhibited in purpose-built rotundas.

In fact, the word ‘panorama’ (Greek for ‘all-embracing view’) was coined in 1791 to describe these paintings. An immersive precursor to cinema and virtual reality, they became a massive hit with the public. As one 19th-century visitor put it: “The effect is very astonishing. I actually put on my hat imagining myself to be in the open air.”

Very few panoramas survive

Because they were too big to preserve, few of these canvases survive. What remain are the initial drawings and paintings.

It may be that the Rhinebeck Panorama is a study for a much larger panoramic canvas, meant to give the illusion that the viewer really was hovering over the city. However, most publicly displayed panoramas were fully circular. Rhinebeck is a semi-circular view.

It might, on the other hand, have been one of a group of watercolours of European cities shown in London in 1809.

The Rhinebeck Panorama focuses on the Thames

The Pool of London is shown busy with ships loading and unloading goods at the wharves of Bermondsey. Despite the sense of peace and prosperity, England was still fighting the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) at this time.

The decisive Battle of Trafalgar had taken place in 1805, shortly before the drawing was made. The Royal Navy's command of the seas was bringing riches to London and Britain. The drawing reminds us of this.

Amid the shipping clogging the foreground is a warship with two masts removed. Unfortunate men forcibly recruited into the Royal Navy – a process known as the press-gang – would have been brought to ships like these.

Which areas of the city are shown?

The streets of Southwark and Lambeth spread out to the left, and somewhere within them, the fire brigade battles a huge blaze.

Over to the right, on the City side, a man flies a kite as fashionable women stroll in the shadow of the Tower of London.

The remodelled London Bridge, free of the houses that once lined it, connects the north and south banks. Carts and carriages rattle across it. In the middle-distance lies Westminster. Beyond are the suburbs of Battersea and Chelsea, and the villages of Fulham, Hammersmith and Kew.

Farther off, the panorama embraces the hills of Highgate and Hampstead and the surrounding countryside. On the horizon, over 20 miles away, we can just see Windsor Castle, a subtle reminder that London is the capital city of the wider nation.

The best way to explore it in detail is by zooming in on our collections page.

William Wordsworth’s view

The Rhinebeck Panorama essentially shows the London conjured a few years earlier by the poet William Wordsworth. In his poem Lines Composed upon Westminster Bridge, 3 September 1802, he wrote:

Earth has nothing to shew more fair […]

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

As coal was burned to heat homes and fuel industry, it’s unlikely London was “smokeless” regularly. When Wordsworth’s sister, Dorothy, crossed Westminster Bridge on a clear day, she found the sight remarkable enough to write in her diary that “the houses were not overhung by their cloud of smoke.” In 1819 Parliament set up a select committee to consider the “problem of smoke from steam engines and furnaces”.

“convincing, but not entirely accurate”

Who made it?

The drawing is the work of three artists. Taken together, their work is convincing, but not entirely accurate.

One artist painted the shipping. Not all match the historical record.

A second painted the cityscape itself. Although generally correct, this has some inconsistencies.

A third painted the distant church spires, but did so out of proportion with the surrounding buildings.

We don’t know who the artists were. However, by the 1830s, the artist-engraver Robert Havell Jr must have had the drawings.

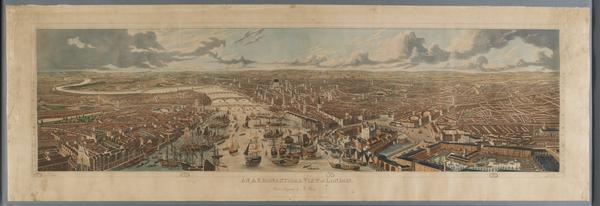

In 1832, he produced the engraving An Aeronautical View of London. It’s closely modelled on the Rhinebeck Panorama, though on a smaller scale and with details – like the new London Bridge – brought up to date.

How did the Rhinebeck Panorama come to London Museum?

Havell later emigrated to the US, settling at Tarrytown on the Hudson River, in New York state.

Apparently, Havell took the panorama with him to America, because this remarkable drawing was discovered lining a barrel of pistols in Rhinebeck, some miles north of Tarrytown, in 1941.

Fortunately, its significance was recognised. In 1998, we acquired the artwork, bringing it back to London after almost 200 years.

The panorama was purchased with the assistance of the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Art Fund and the V&A Purchase Grant Fund.