A panoramic history of London

Since at least the 17th century, artists have created panoramic views of London, often with what appears to be amazing accuracy. The panoramas in our collection were made between 1630 and 2000, starting long before aerial photography was possible, and giving us a precious sense of how the city has evolved.

Across London

1620–2000

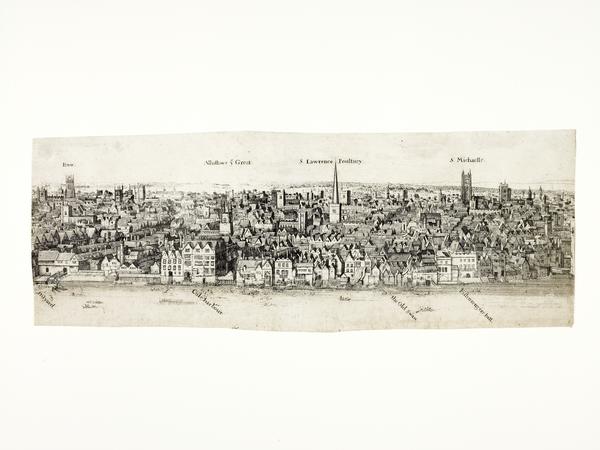

London from Southwark, around 1630

This painting by an unknown artist is one of only three surviving paintings of the city from before the 1666 Great Fire. You can see Old St Paul’s Cathedral and the old London Bridge, which was topped by houses and shops. The heads of executed rebels are also visible on the bridge’s gatehouse.

London and the Thames from Greenwich, 1620–1630

This is the earliest painted view of London from a distance. The view is from Blackheath, with St Paul’s and Southwark Cathedral just visible on the horizon. Closer to us, there’s the Isle of Dogs and the villages of lower Deptford and Greenwich. Again, the artist is unknown.

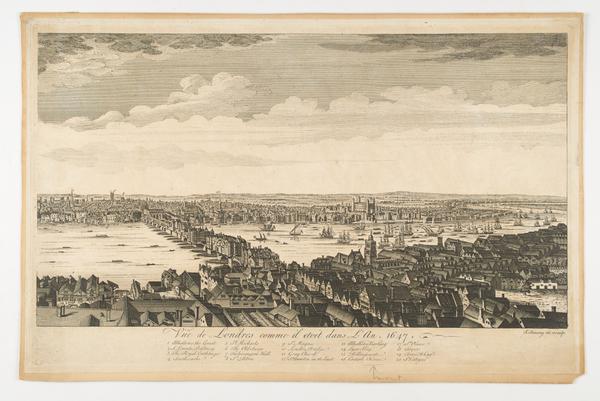

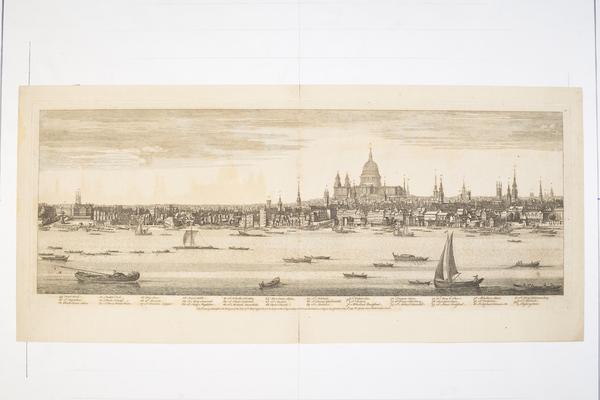

Wenceslaus Hollar, 1647

As with other early views of London, Hollar's looks north from the south side of the River Thames. We don’t know exactly how these detailed works were made. Artists may have climbed Southwark Cathedral or Sydenham Hill for the views, or drawn from various points along the river. They may have used glass lenses and mirrors to see from a distance or to nail the perspective, possibly even projecting and tracing the image. But everything had to be combined in the studio to compose an artificial, flattened view showing the whole city.

Buck brothers, 1749

This is one sheet of five making up a panorama by brothers Samuel and Nathaniel Buck. Again, it’s a view from Southwark Cathedral which distorts the perspective to squeeze in both Westminster and the City of London. Nevertheless, it’s impressively accurate. On this section, you can see how the skyline was still dominated by church steeples and towers – and the new St Paul’s dome.

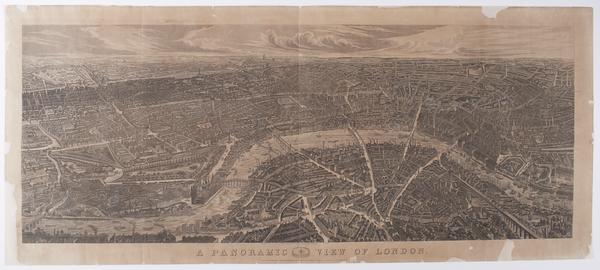

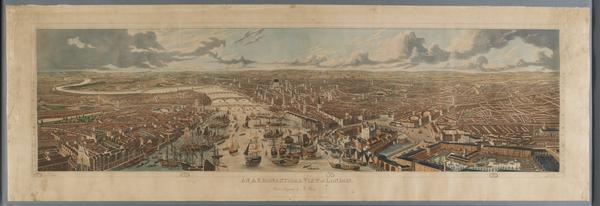

Robert and Henry Barker, 1791

Robert and Henry Barker’s panorama of Edinburgh from Calton Hill, first shown in London in 1789, helped start a craze for displaying enormous panoramas in specially designed round buildings. A visit might have been a similar experience to a modern immersive art exhibition. Few of these full-scale panoramas survive, but our collection includes reproductions and early designs. The print pictured here is the father-and-son duo’s view of London from Albion Mills, a steam-powered flour mill in Southwark.

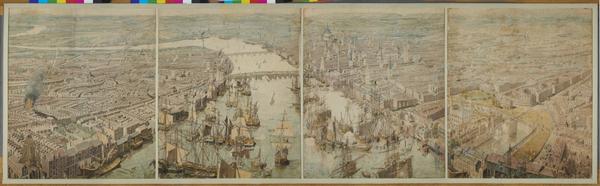

The Rhinebeck Panorama, 1806

This stunning pencil and watercolour drawing shows the city from a very different perspective – high in the air, roughly where Tower Bridge stands today. The novel 180-degree view of the city and the river shows ships waiting in the Pool of London. Countless small details – a funeral, a fire, a kite – reward a closer look. The three artists who made it are unknown, and it’s likely to have been a study for a much larger panoramic work. Amazingly, the artwork was discovered in a barrel in the US in 1941.

The Prevost Panorama, 1815

This six-metre long panorama is the largest in our collection. But, again, it’s not even the finished work. The artist Pierre Prévost’s finished panorama, displayed in a rotunda in Paris, was an enormous 32 metres long. This panorama took St Margaret’s Church in Westminster as its viewpoint. In this section, we look north. We’ve added our own labels to the image to help you get your bearings.

Maclure, MacDonald & MacGregor, 1850–1855

This is one of 10 panels making up a 19th-century panorama of the Thames’ north bank. Here, traffic crosses the old Blackfriars Bridge.

Lawrence Wright, 1948–1952

Lawrence Wright’s watercolour panorama shows London as it recovers from the Blitz, viewed from the city’s icon of survival, St Paul’s Cathedral. This view looks roughly east, toward Cannon Street Station, Greenwich, the Tower of London, the Monument and Tower Bridge.

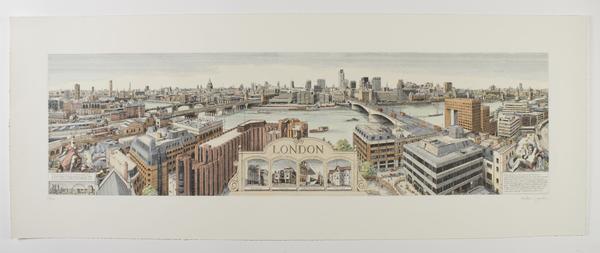

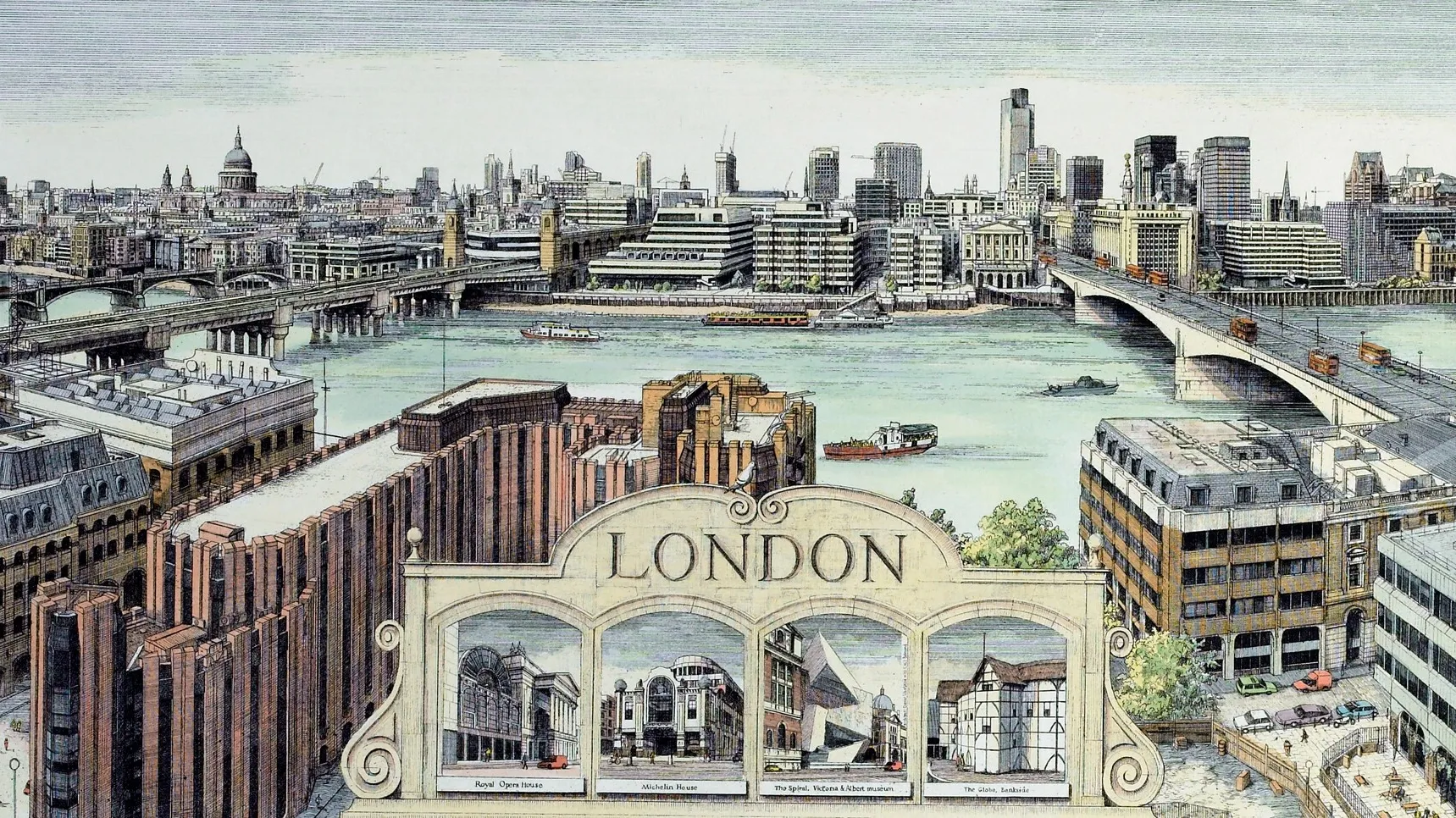

Andrew Ingamells, 2000

Ingamells’ New Panorama of London is inspired by Hollar’s panorama from 400 years earlier, which used the same viewpoint. For a 17th-century observer, the modern city would be barely recognisable. In the 21st century, technology has made it infinitely easier to capture panoramic aerial views of the city. But whether painted or photographed, seeing the sheer scale and density of our city still retains some wonder.