A Little Italy in London

London’s Little Italy emerged around Clerkenwell in the mid-19th century when Italian people found work there as musicians and ice cream sellers. Later, Soho became the new centre, drawing young Londoners to its restaurants and bars.

Clerkenwell & Soho

Since 1830s

London’s big links to Italy

London’s Italian connection goes far beyond the Romans. In the 1830s, the city’s own ‘Little Italy’ developed as thousands of Italian people gravitated to Clerkenwell, Saffron Hill and Hatton Garden. Today, this area overlaps the southern sections of two boroughs – Camden and Islington.

Soho, in the West End, emerged as a second Italian hub soon afterwards. By the 1950s, its Italian restaurants and espresso bars were popular hangouts for young Londoners.

Today, neither area is so uniquely or obviously Italian. But rather than disappearing, Italian people and their culture have spread across London. Instead of a Little Italy, practically all of London now bears the influence of Italian people who’ve called this city home.

Italian people in London before the 19th century

Many Italians passed through London before a true community took hold in the 19th century. These were mostly from the elite of Italian society – merchants, artists, musicians, scholars and skilled craftspeople.

In the medieval period, Italian banking firms established themselves in the City of London. Lombard Street takes its name from the Lombardi firm.

In the 18th century, the artist known as Canaletto lived on the fringes of Soho, and another artist, Giovanni Battisti Cipriani, painted his designs onto the lord mayor’s coach. The coach is now part of our collection.

Where is London’s Little Italy?

London’s first Little Italy developed in the 19th century around Clerkenwell, Saffron Hill and Hatton Garden.

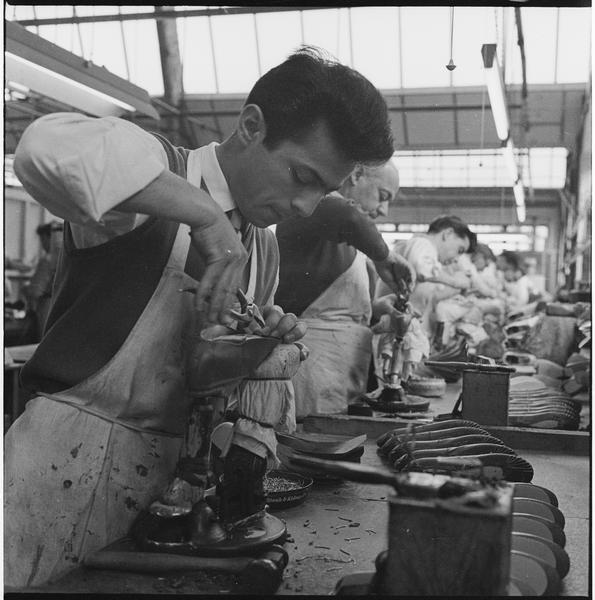

Italian people came to London for different reasons, from different parts of the country. There were nationalist refugees, artists’ models and makers of scientific instruments and small statues. Italian knife grinders also came to dominate the London trade in the 20th century.

The largest group were from the mountains of Tosco-Emiliano, compelled to seek work abroad by poverty at home.

They arrived from the 1830s, following family, friends and employers. Most settled in cheap accommodation in Hatton Garden, Saffron Hill and Leather Lane, where slums had grown as London’s population boomed.

Organ grinders and exploitation

Many worked as street entertainers. ‘Organ grinders’ playing their barrel organs became a common sight and sound, sometimes appearing with monkeys.

Often these were boys exploited by men known as padroni, who’d recruited them from Italy. In 1875, a newspaper described how the boys “live in parties of from forty to fifty in one house”.

Some commentators highlighted the exploitation. Others saw the music as a noisy nuisance. In 1820, The Times reported “The public have of late been exceedingly annoyed by the appearance of a number of Italian boys with monkeys and mice wandering about the streets, exciting the compassion of the benevolent.”

The author Charles Dickens mentions organ grinders and their white mice in his novel Little Dorrit, published between 1855 and 1857. He also used Saffron Hill and its gangs as inspiration for Fagin’s pickpockets in Oliver Twist.

The Italian school and church

As the community developed, local institutions appeared. In 1841, the exiled Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini opened a free school on Greville Street, offering free education to local Italian children.

Clerkenwell’s St Peter’s Italian Church followed in 1864. Its annual festival of the Madonna del Carmine began in 1883, becoming the first Catholic procession in London since the 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

The Madonna del Carmine procession in progress.

“Towards evening, about seven o'clock, the ice-men begin to return. From all points of the compass they approach Saffron Hill”

Adolphe Smith, Street Life, 1877

Italian ice cream and a boom in business

From around 1880, the number of Italian street musicians gradually decreased, while food businesses grew.

Ice cream was a winning product and became a craze in Victorian London. Before cones came into use around 1905, customers ate ice creams from small glasses known as penny licks, handing them back to the vendor once they were finished.

Writing in 1877, journalist Adolphe Smith described the end of a day of trading across the city: “Towards evening, about seven o'clock, the ice-men begin to return. From all points of the compass they approach Saffron Hill.”

Ice came to the capital from Norway and was transported to ice wells in Clerkenwell via the Regent's Canal. By 1901, London's natural ice trade – for both ice cream and preserving food – was entirely run by Italian business people living in Little Italy.

A major player was Carlo Gatti, a Swiss Italian who’d arrived in 1847. Gatti started selling roast chestnuts and ice cream on the street, before making a fortune as an ice importer. He soon owned restaurants, ice cream shops and a music hall.

Slum clearances and Soho

In the late 19th century, overcrowding around Saffron Hill led authorities to begin ‘slum clearances’. Two new roads, Clerkenwell Road and Rosebery Avenue, cut through the area.

The unpleasant task of asphalting the roads provided many Italian Londoners with work, but the local community gradually dispersed.

The largest portion went to Soho, where a second Little Italy had formed around northern Italian communities from Piemonte and Lombardia. Many worked as cooks or waiters in West End hotels and restaurants.

By the 1920s, Italian food businesses were flourishing. There were Italian restaurants in Soho and Mayfair, like Quo Vadis and Quaglino’s. Michele Manze, born in southern Italy, opened his first pie and mash shop in Bermondsey in 1902.

In Clerkenwell, some Italian businesses continued into the 21st century, including L Terroni & Sons deli, which opened in 1878.

Hostility to Italian communities in London

Italian people who arrived in Britain faced prejudice and hostility – sometimes for being Catholic, or simply because they were ‘foreign’.

During the Second World War (1939–1945), when fascist Italy fought alongside Nazi Germany, shops in Soho had their windows smashed. The British government sent thousands of Italian men to the Isle of Man for being ‘enemy aliens’.

The Italian influence on post-war Soho

The end of the war in 1945 saw another boom in migration. British recruiters looked abroad for workers, while Italian catering businesses recruited more friends and relatives.

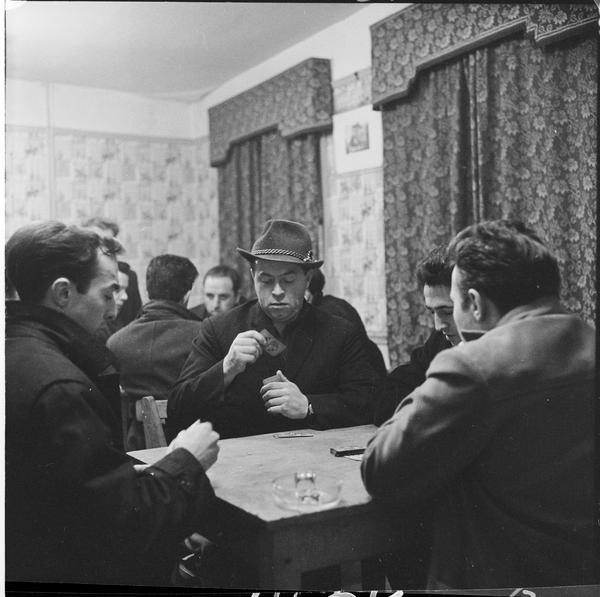

In the 1950s, Italian espresso bars in Soho became popular with young Londoners. The first was Moka, which opened on Frith Street in 1953.

The area was a hub for the emerging youth cultures of the 1950s and 1960s. Mods in particular were heavily influenced by Italian style.

In the decades afterwards, Italian bars, cafes, delis and restaurants became integral to the area’s appeal.

Bianchi’s restaurant on Frith Street was popular with politicians and celebrities. We have some of its bookings diaries and a menu in our collection. The head waiter there, Elena Salvoni, became famous in her own right as the ‘Queen of Soho’.

Nearby Bar Italia remains an institution, while the Lina Stores deli expanded from its Brewer Street shop to a chain of restaurants.