London’s Blitz: A city at war

Starting on 7 September 1940, London faced 57 straight nights of bombing by Nazi Germany, part of a concentrated eight-month campaign known as the Blitz.

Across London

September 1940 – May 1941

Death, destruction and perseverance

When the Second World War erupted in Europe in 1939, the battlefields seemed a long way from London. But between 1940 and 1941, Britain’s towns and cities were bombed persistently by German planes in an attempt to force Britain out of the war.

London was one of the main targets. Thousands died. Many more were injured or left homeless. Areas of the city were left unrecognisable. But Britain didn’t surrender.

The “Blitz spirit” shown by people in the face of the bombing – bravely pushing through and pulling together – is still celebrated as part of our national identity.

But it’s not the full story. The Blitz terrified and traumatised people, exposing them to the horrors of war. And among London’s rubble there was looting and a thriving black market.

Preparation and the “phoney war”

Before the war began, the government feared that bombing could kill hundreds of thousands of civilians, or spark mass panic and social unrest.

Gas masks were handed out. Children were evacuated. Men and women not already working with the military took on extra voluntary roles as firefighters, medical workers and air-raid wardens.

Blackouts were enforced – reducing street light to prevent German bombers navigating by the city’s glow. Local authorities constructed communal shelters in public spaces. Those lucky enough to have gardens were given materials to build their own shelters.

Despite all the preparation, there was no bombing between the outbreak of war in 1939 and the summer of 1940. Many Londoners relaxed. Some labelled this the “phoney war”.

When did the Blitz begin?

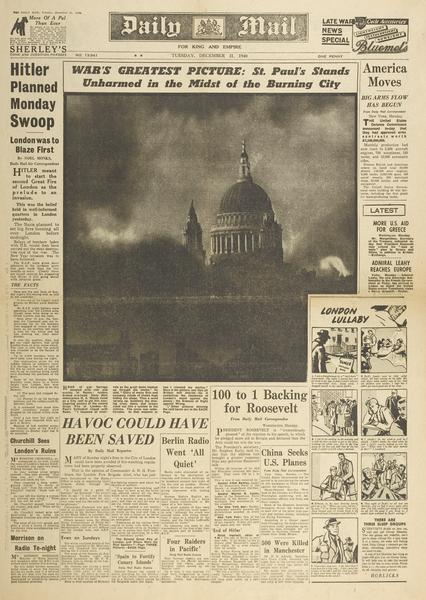

Peace in London ended on 7 September 1940, a day which became known as Black Saturday.

Starting around 4pm, hundreds of German planes dropped bombs on warehouses and homes in east London’s docks. Incendiary bombs started huge fires.

The bombing killed 430 people and injured 1,600. But it was just the start. London was attacked for 57 nights in a row, and the bombing continued regularly for months afterwards, spreading to other cities around Britain.

The most intense raid began on the night of 10 May 1941 – setting off an enormous blaze which covered an area larger than the 1666 Great Fire of London. 1,500 people died and 11,000 homes were destroyed.

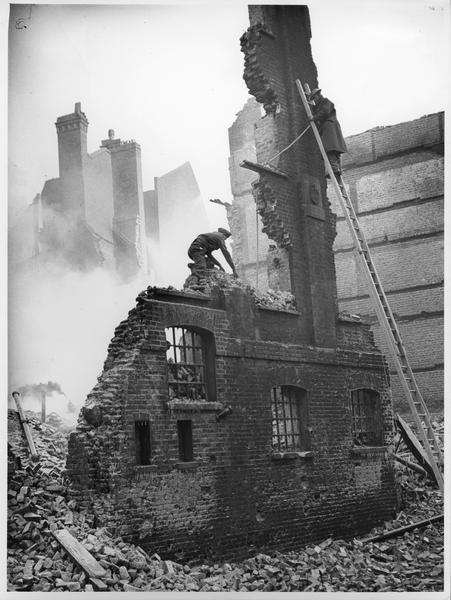

Which parts of London were affected?

The densely populated East End and its docks were frequent targets. The aim was to disrupt the supply of vital food and goods entering the port of London.

But bombs fell in almost every part of the city. As well as tens of thousands of houses, bombing damaged the Houses of Parliament, Buckingham Palace and Tower of London. Amid a raid on the City of London, the iconic dome of St Paul’s cathedral remained standing, becoming a symbol of London’s survival.

How did the Blitz end?

After the attack on 10 May 1941, there wasn’t another major bombing raid for three years. Germany changed focus, turning east to Russia.

However, the Blitz wasn’t the last threat Londoners faced. In 1944, German V1 and V2 rockets were launched at the city. On 25 November 1944 a rocket killed 160 people in New Cross, south-east London.

How many people were killed during the Blitz?

Across Britain, around 43,000 civilians were killed during the Blitz.

In London, almost 30,000 Londoners were killed during the Blitz and the V1 and V2 rocket attacks of 1944.

Londoners took shelter underground

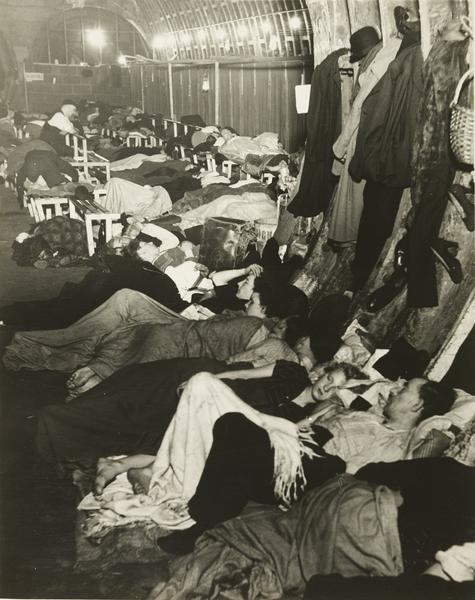

At the beginning of the war, officials banned people from using Tube stations as shelter. They wanted to keep trains running, and feared Londoners would become scared to leave the shelters.

But east Londoners in particular protested that they were bearing the worst of the bombing without enough shelter. People soon started heading underground when they heard the sirens.

Officials gave in and started managing the stations and providing facilities. Just weeks into the Blitz, around 120,000 people a night were using Tube stations for shelter.

However, a far larger number of Londoners took shelter elsewhere. Some used official shelters. Some stayed at home. Many used informal communal shelters, like shop basements, church crypts or the huge Tilbury shelter, underneath a warehouse in Whitechapel.

Shelters were often dark, damp and crowded. People from different backgrounds shared the same space, and this sometimes led to conflict. But there was often a sense of community, with people singing, drinking and celebrating Christmas together.

“London Can Take It!”

UK government propaganda film, 1940

The Blitz led to an increase in crime

The Blitz did encourage people to rally together, but desperation, along with the more selfish side of human nature, turned some Londoners to crime.

The disruption of the bombing, the darkness of the blackout and the rationing of food and clothing provided an excellent opportunity for anyone wanting to exploit the situation. Many police officers had left to become soldiers, while some prisoners were released early.

People stole safes, pulled rings from the fingers of bomb victims and falsely claimed compensation for bombed houses they’d never lived in.

Crime also rose because, for the first time, the government controlled every aspect of day-to-day life. Not covering a window during the blackout could result in a fine. Compulsory work orders meant you could be punished for taking time off without permission. Many struggled to follow all of the rules – something we can recognise from our experiences of the Covid-19 lockdowns.

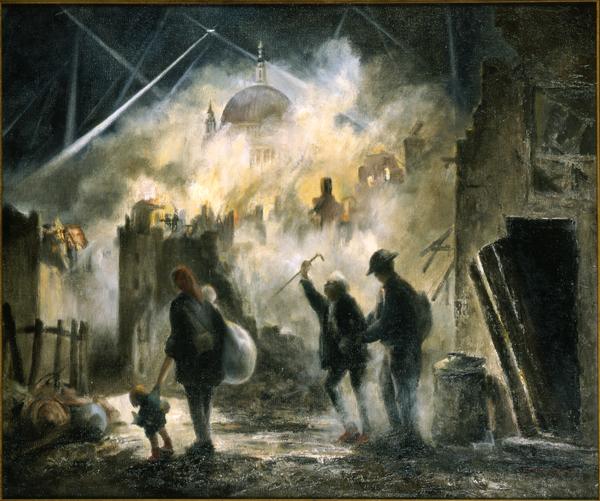

The Blitz spirit

Ordinary people showed incredible bravery to continue with their lives during the Blitz. Many did more than that – taking on extra duties to treat or rescue people, to put out fires or to give out food and clothes to the homeless and hungry.

But the idea of the “Blitz spirit” was also pushed by the government to boost morale. They feared what might happen if Londoners turned against them and the war. London Can Take It! declared the title of a 1940 propaganda film.