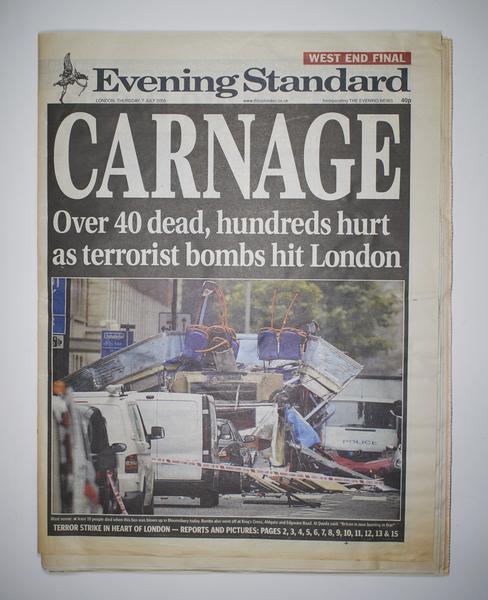

The 7/7 London bombings, 2005

On the morning of 7 July 2005, four suicide bombers detonated their devices on London Underground trains and a double-decker bus, killing 52 people and injuring hundreds more.

Inner London

7 July 2005

The London bus destroyed at Tavistock Square.

21st-century terror

On 7 July 2005, the peace of a summer’s day in London was shattered by the first suicide bombings on English soil.

The attack targeted innocent commuters in the morning rush hour. Some still glowed with the news of the day before – the announcement that London would host the 2012 Olympic Games.

Two weeks later, five men tried, but failed, to repeat the attacks on London’s transport network. In the hunt that followed, an innocent man was killed by armed police officers.

Motivated by extreme Islamist ideas, the attacks spread fear and anxiety. Muslims suffered increased Islamophobia. But there was also resilience – a determination not to let the attacks divide this diverse city.

While Londoners continued with their lives, they didn’t forget the victims of the attacks and created lasting memorials in their honour.

“Bloodied and dazed commuters emerged from the tunnels”

Where were the 7/7 London bombings?

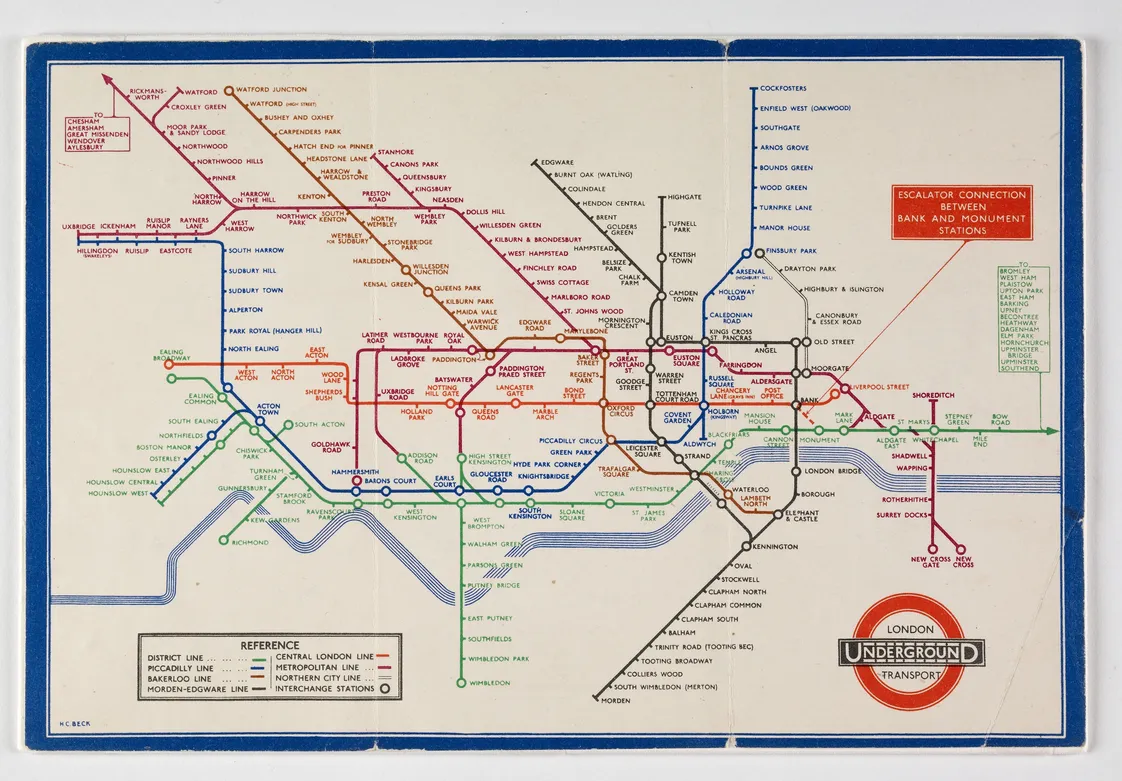

Just before 9am, three suicide bombers carrying explosives in rucksacks detonated their devices independently on London Underground trains travelling through inner London.

One exploded between Liverpool Street and Aldgate. Another detonated between Edgware Road and Paddington. The most deadly explosion came between King’s Cross St Pancras and Russell Square, killing 26 people.

Roughly an hour after the first explosions, a fourth bomb was detonated on a London bus at Tavistock Square, killing a further 13 people.

The photos of the red London bus with its upper deck split violently open became the defining image of 7/7.

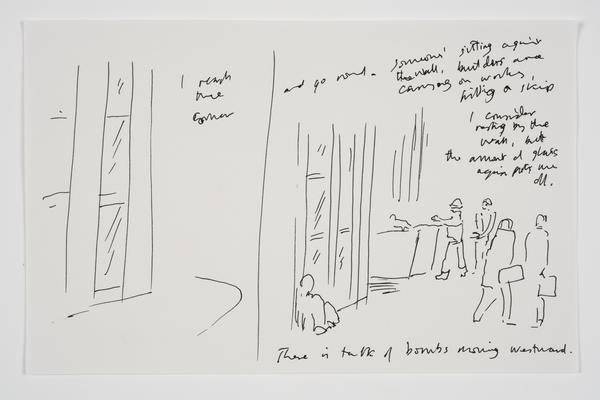

Bloodied and dazed commuters emerged from the tunnels, helped by emergency workers. The London Underground network was closed, and almost all buses were suspended.

Surreal scenes followed as tens of thousands of Londoners spilled onto the street, confused by the lack of information and struggling to make their way home.

Mobile networks went down, unable to cope with the surge in calls as people tried to contact loved ones. Meanwhile, authorities desperately tried to piece together what had happened.

How many people died on 7/7?

A total of 52 people were killed. More than 700 were injured, some losing limbs. The mental scars run further, still affecting passengers and the members of the emergency services who reacted.

The victims were typical of those who crowd onto buses and the Tube every day. The majority were born in the UK, but there were also many people from other countries, including Poland, Vietnam, Ghana, Mauritius and Turkey.

There was Arthur Frederick, 60, a museum security guard. Ihab Slimane, 24, spending a summer in London to improve his English. Samantha Badham, 35, and Lee Harris, 30, partners taking the Tube together before work. Marie Hartley, 34, an artist and mother of two children. And 47 more, each with their own reason for being where they were that day. Each with a plan for their morning, their evening, their week.

There were also inspiring stories of heroism and survival. Martine Wright lost both her legs, but went on to compete in the London 2012 Paralympic Games.

The 7/7 memorial in Hyde Park.

Honouring the dead

In our collection, there’s a book of tributes by the families and friends of the 52 people who were killed. Inside, they share their intimate memories of those they lost, hoping to preserve some part of their spirit.

The book was previously held at St Ethelburga’s Centre for Peace and Reconciliation in Bishopsgate, where it was a focal point for visitors paying their respects.

Those who died are also commemorated at a permanent memorial in Hyde Park, where 52 steel pillars are arranged in clusters representing the four locations of the attacks.

Who were the suicide bombers?

The bombers were British men who began their journeys on 7 July from their homes in West Yorkshire and Luton. Their British nationality meant they were labelled as ‘home-grown’ terrorists.

All four were killed by their homemade explosives, just as they’d planned. The bombers were inspired by the militant Islamist group al-Qaeda, who were linked to the Madrid train bombings in 2004, the 9/11 attacks in New York in 2001 and the 1998 bombings in Kenya and Tanzania.

Al-Qaeda’s ideology pitted it against the US and its allies – including the UK – for their presence in the Middle East and the wars they’d fought in Iraq and Afghanistan.

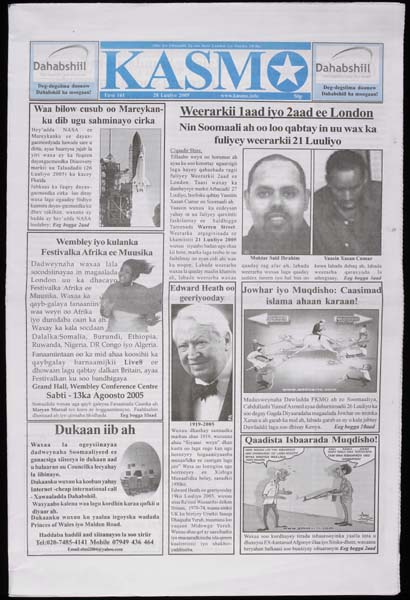

21 July 2005: A second attack

Just two weeks after 7/7, a group of five men acting independently of the first quartet attempted a similar attack.

After leaving an address in north London, four of them split up to detonate their bombs aboard trains leaving Oval, Warren Street and Shepherd’s Bush, and on a bus on Hackney Road, Haggerston. None of their homemade bombs exploded correctly. The fifth man didn’t carry out the plan. He dumped his bomb at Little Wormwood Scrubs park in west London instead.

The men fled, sparking an intense manhunt. They were all later arrested and convicted.

The killing of Jean Charles de Menezes

Amid the search, two armed police officers mistakenly killed an innocent man, Jean Charles de Menezes. He was shot multiple times in the head on board an Underground train at Stockwell station.

A tribute to de Menezes outside Stockwell station.

The Metropolitan Police claimed the killing was lawful. However, an inquest jury rejected the police’s account of the shooting. The force was later found guilty of health and safety failures, fined £175,000 and ordered to pay £385,000 in legal costs. De Menezes’ family were paid compensation in a private settlement.

No police officers have been prosecuted. The officer in charge of the botched operation, Cressida Dick, was later promoted to commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, the force’s most senior role.

7/7’s impact on Muslims

Despite Muslim community leaders immediately and publicly condemning the bombers’ actions, the aftermath saw an increase in faith-related hate crimes. Islamophobia festered in some sections of British society, affecting both Muslims and anyone wrongly identified as one.

In the 2006 local elections, the far-right, anti-immigration British National Party more than doubled its number of councillors in England, winning 46 seats.

London’s Muslim communities have also been affected by the government’s controversial Prevent scheme. Prevent aims to challenge ‘home-grown’ terrorism by engaging and supporting people who are at risk of radicalisation.

Critics have questioned its effectiveness, its bias in targeting Islamist ideology over far-right extremism, and the damaging impact of placing increased suspicion on already marginalised communities.

“The majority of the transport network was running the next day”

Did London change after the attacks?

In some ways, London returned to normality very quickly after 7/7. The majority of the transport network was running the next day. Our collection includes the boarding pass of an Irish visitor who landed in London on 7 July. They recalled visiting the Hampton Court Palace Flower Show, which ran as planned the day after 7/7.

Spurred on by inquiries, the various services – police, ambulance, fire, Transport for London (TfL) and the Security Service (MI5) – re-evaluated their approach to preventing and handling future incidents. The communications technology used in the Underground was upgraded. And changes were made to coordinate between services more effectively.

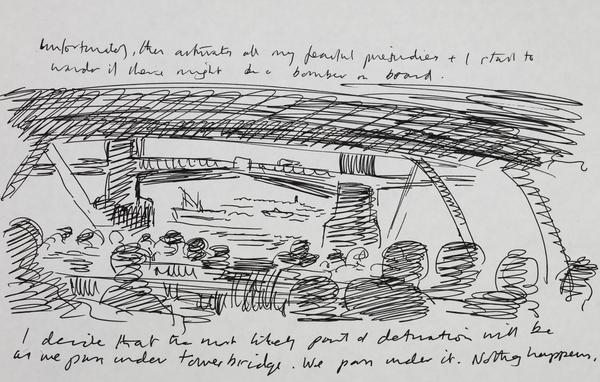

People felt scared and anxious in the aftermath of the attacks, especially before the police established that the 7/7 bombers had died in the blasts, and during the search for the 21 July bombers.

But terrorism in London was not new. Many Londoners had lived through the IRA’s deadly attacks on the city between the 1970s and 1990s.

We’re Not Afraid

Within hours of the 7/7 attacks, London web designer Alfie Dennen created the We’re Not Afraid website, a platform for people to post images echoing his message of resistance to terrorism.

At a time before social media was widely used, tens of thousands of people from around the world uploaded images in an outpouring of support. Some of these posts are now part of our collection.

Exactly a week after the attack, a Londoner printed stickers with the same message – “We Are Not Afraid” – overlaid on the London Underground logo. They handed out hundreds to commuters and TfL staff, who were happy to wear them.

Over a decade later, the same image from the sticker went viral on social media after the London Bridge terror attacks in 2017. It was a sign that the spirit of defiance in the face of terrorism had endured.