A thousand years of Billingsgate Market

Billingsgate Market is London's premier fish hub. It’s evolved from riverside sheds to modern facilities, moved from the City of London to West India Docks, and the UK's largest inland fish market faces yet more change.

West India Docks

Since 1016

Scales, sales and fishy tales

For over 1,000 years, Billingsgate has been the beating heart of London's fish trade. The market began beside the River Thames, on a site between London Bridge and the Tower of London. It grew to new heights there in the 1800s, gaining a trading hall designed by architect Horace Jones in the 1870s.

Billingsgate has been an integral part of London’s economy. But it’s also home to a rich working culture, be it porters and their ‘bobbin hats’, or the distinctly sweary way of speaking.

The market moved to its current spot near Canary Wharf in east London in 1982. As of 2025, it was still the UK’s largest inland fish market, responsible for the sale of about 25,000 tonnes of fish and fish products each year. Plans are now in motion for yet another move.

How did Billingsgate begin?

Early records refer to the market as ‘Blynesgate’ or ‘Byllynsgate’. The name could refer to a watergate at the south side of the City where goods were landed. One theory is that the land was owned by a man named 'Biling'. Or the name may come from Belin, a king who ruled around 400 BCE.

A major excavation in 1982 revealed evidence of waterfront buildings and wharves in the area dating back to Roman times.

The first toll regulations – which charged boats arriving at Billingsgate based on their size and goods – date back to 1016, and mention traders from France and Belgium.

With Billingsgate being one of the main places for ships to unload their fish, a market grew at the foot of Lower Thames Street. The market dealt with the sale of corn, salt and fruit, but fish was always the primary trade.

In 1698, an act of Parliament made Billingsgate “a free and open market for all sorts of fish whatsoever”. The sale of eels was initially restricted to Dutch fishermen – their reward for helping to feed Londoners during the Great Fire of 1666.

By the 17th century, it had overtaken the dock at Queenhithe to become London's ‘larder door’ for fish.

The Victorians levelled up Billingsgate

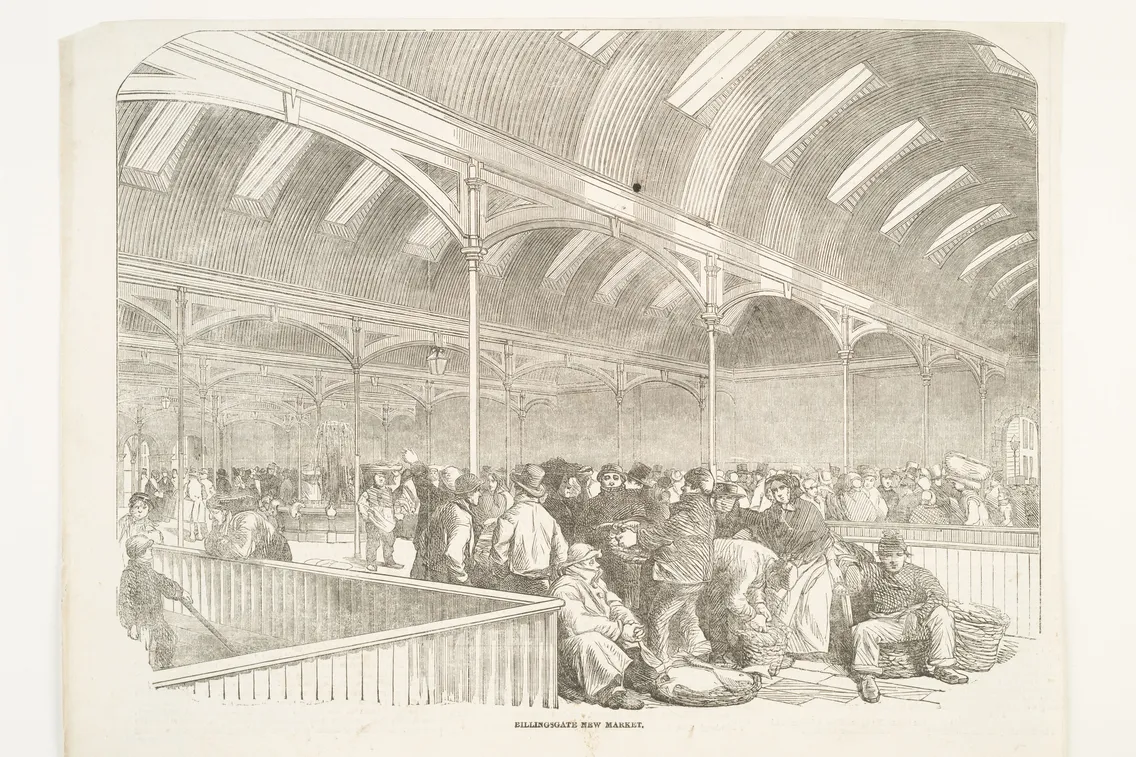

Surprisingly, for a market central to London's fish trade, there was no trading hall until the 1850s. Fish was sold in the open air, from stalls and basic wooden sheds.

The first purpose-built market was constructed in 1850 on Lower Thames Street. But these buildings couldn't handle the growing trade, leading to a complete rebuild in 1874–1877.

Horace Jones, architect and surveyor to the Corporation of London, designed the new French Renaissance-style building. He also designed Smithfield Market and Tower Bridge.

Jones' design served the market for over a century. His elegant creation became Grade-II listed and survived even after the market moved in 1982.

Life inside the Victorian market

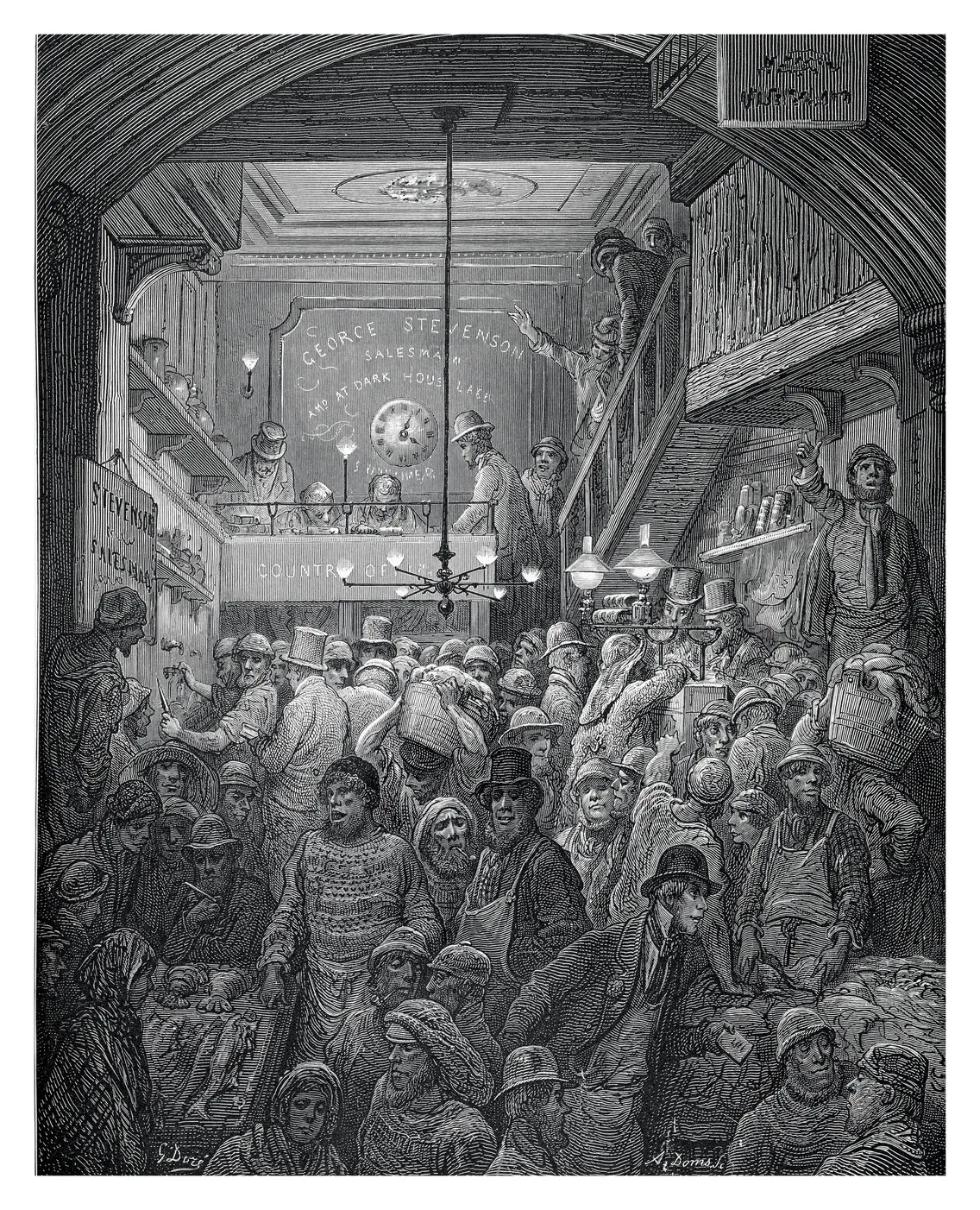

The Victorian-era Billingsgate was a sensory spectacle. Beginning at 5am every day, the market floor was a cacophony of competing cries as traders stood on tables shouting their prices through the thick odour of fish.

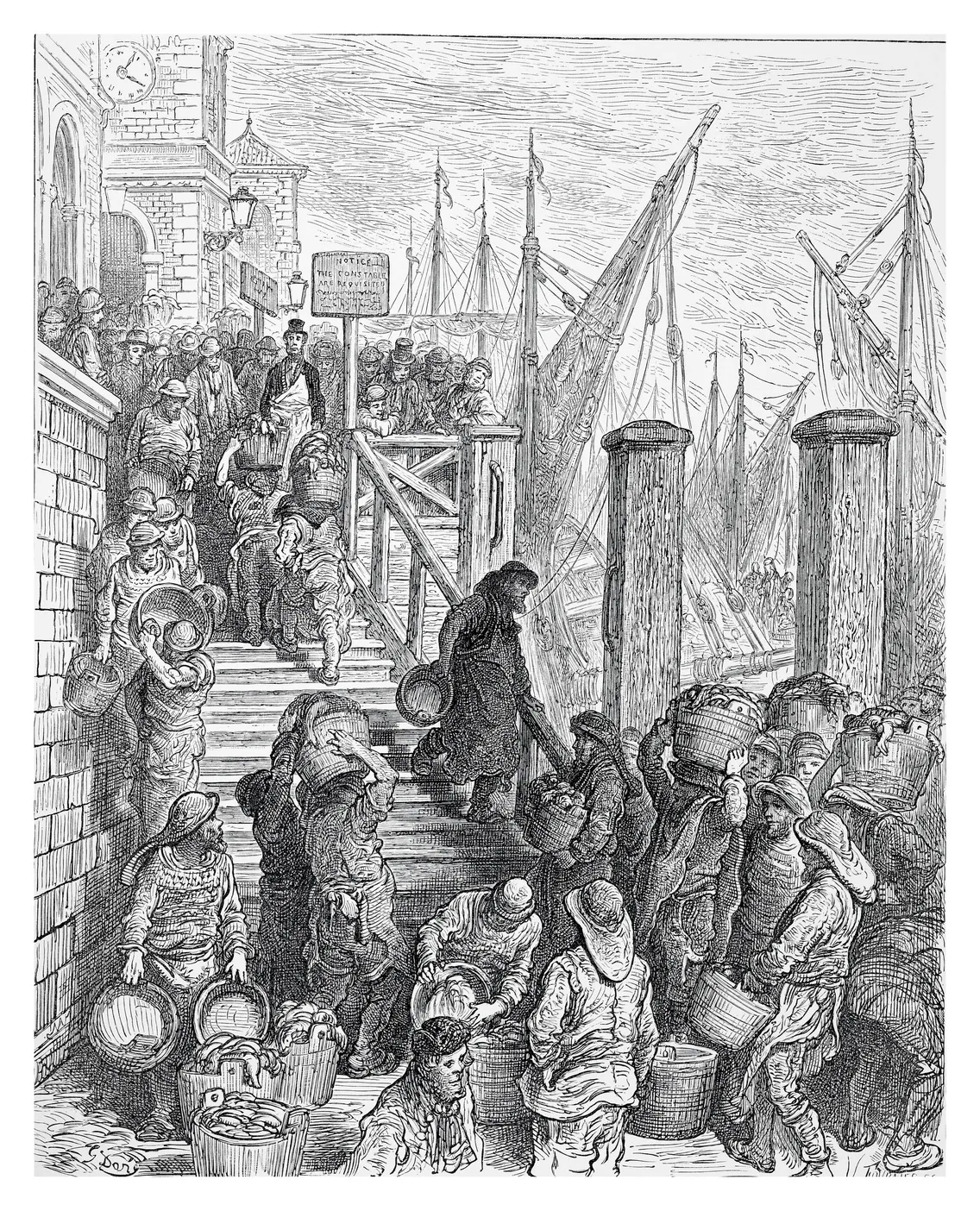

The “picturesque tumults” of Billingsgate are described by journalist William Blanchard Jerrold and illustrated by Gustave Doré in their 1872 book London: A Pilgrimage, which is part of our collection.

It’s easy to imagine how, in this competitive, hard-working atmosphere, the spiky, sweary ‘Billingsgate language’ became common, giving rise to the saying ‘swear like a Billingsgate fishwife’.

Billingsgate porters were crucial

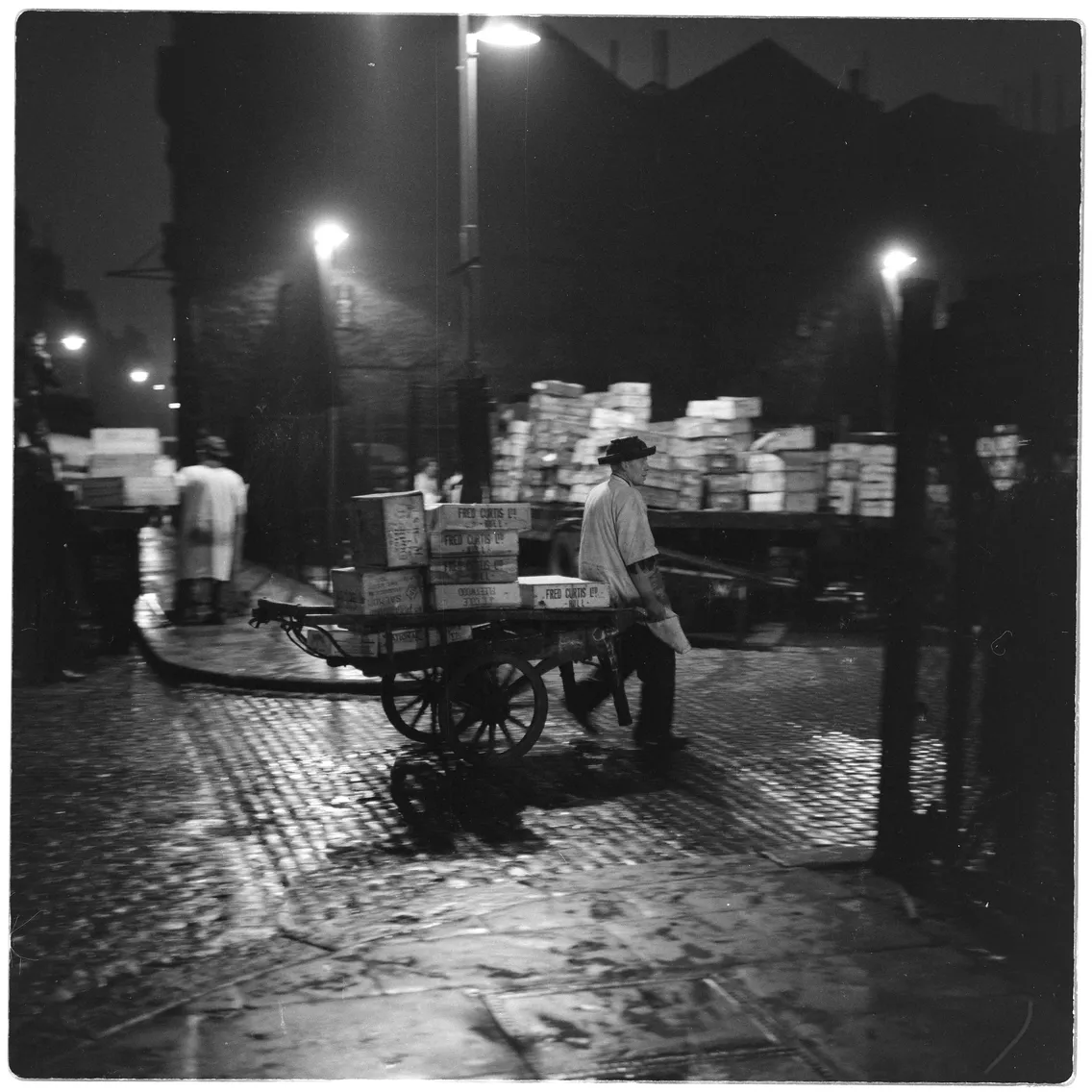

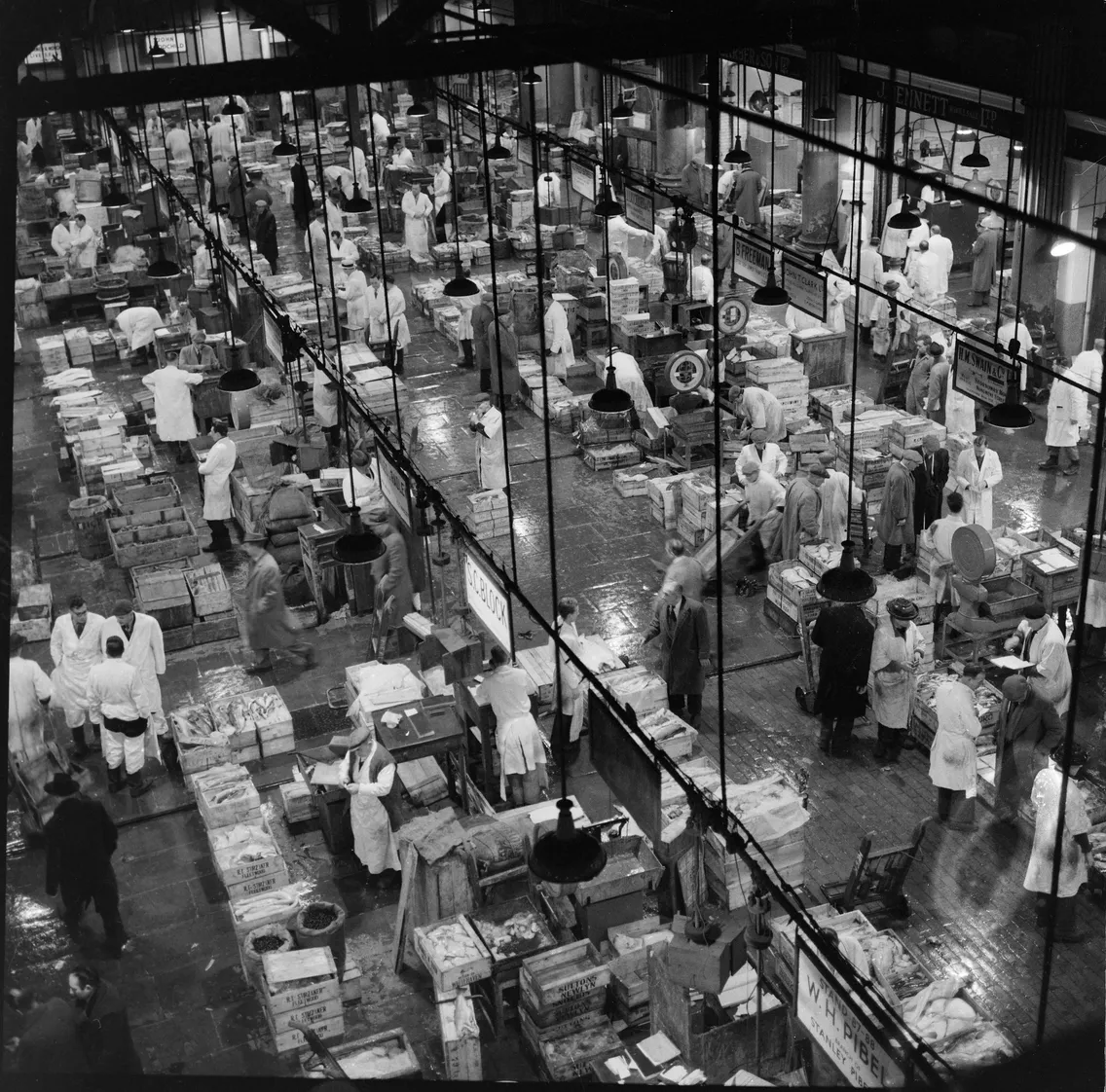

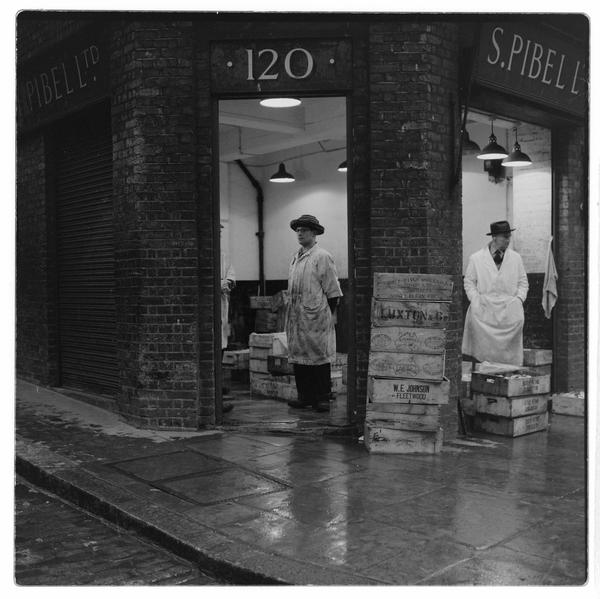

Porters unloaded and transported the fish, and were essential to the buzzing market. A series of photos in our collection from 1958 by Bob Collins captures the organised chaos.

In 1876, the Corporation of London introduced regulations requiring all porters to be licensed. Traditionally, there were 240 porters at Billingsgate. All started their day at the crack of dawn, moving the fish samples from the delivery vehicles to the merchants' stands.

Their distinctive ‘bobbin hats’ were uniquely practical, with flat crowns that helped them balance fish boxes on their heads. The hats also protected their wearers from melting ice and fish slime trickling from boxes. We have two of the hats in our collection.

The hats are said to have lent their name to ‘bobbin money’, the additional sum customers paid for each purchase delivered to them.

Famous faces at the fish stalls

The author George Orwell is said to have walked around Billingsgate’s stalls, perhaps gathering inspiration. The notorious Kray twins, East End gangsters, were known to ‘work’ in the market.

Billingsgate traditionally revolved around families. Small family-run trading firms and portering jobs passed through generations, with fathers, sons, uncles and cousins working side by side. Women were part of it too, often managing finances as cashiers.

However, actor Michael Caine, whose father worked as a fish porter, was not one to carry on this family tradition.

Comedian Micky Flanagan was the same, though he worked briefly as a fish porter in his teenage years: "It was hard, an early start, freezing cold, putting on damp clothes, delivering fish in the rain... it wasn't for me."

The move to London docks

After 900 years at its original Thames Street location, Billingsgate relocated to West India Docks in Tower Hamlets in 1982. Many objects from the market made their way into our collection, including signs, tokens and bell weights. The original market bell moved with the market, ringing to announce the beginning of trading on 19 January 1982.

The 13-acre site near Canary Wharf was, at the time, touted as the most modern fish market in the whole of Europe. The large trading hall could hold about 98 stands and 30 shops, an 800-tonne freezer store and an ice-making plant.

Is Billingsgate closing?

In 2022, the City of London, which owns and manages Billingsgate, announced its decision to redevelop the Canary Wharf market site for housing. A move to Dagenham was considered, then abandoned.

Progress came in 2025, when the City of London announced plans to move both Billingsgate and Smithfield markets to Albert Island, at Royal Docks in east London. After years of uncertainty, it offered a tantalising new chapter for Billingsgate and its traders.

Even before this decision, the market has survived centuries of transformation, maintaining traditions while embracing the future. In 2021, artist and educator Pat Wingshan Wong documented this through her Barter Archive project, a part of which is now in our collection.

She sketched the daily life of fishmongers, porters and workers, trading her drawings for their stories and meaningful objects. The artist’s work preserves the memory of Billingsgate at West India Docks before its next move.