Thomas Barnardo’s crusade against child poverty

Thomas Barnardo founded pioneering children’s homes in London in the 19th century. He aimed to help the growing number of orphans and children whose parents couldn’t support them, but followed a controversial policy of sending some abroad.

East End

1845–1905

'No destitute child ever refused admittance'

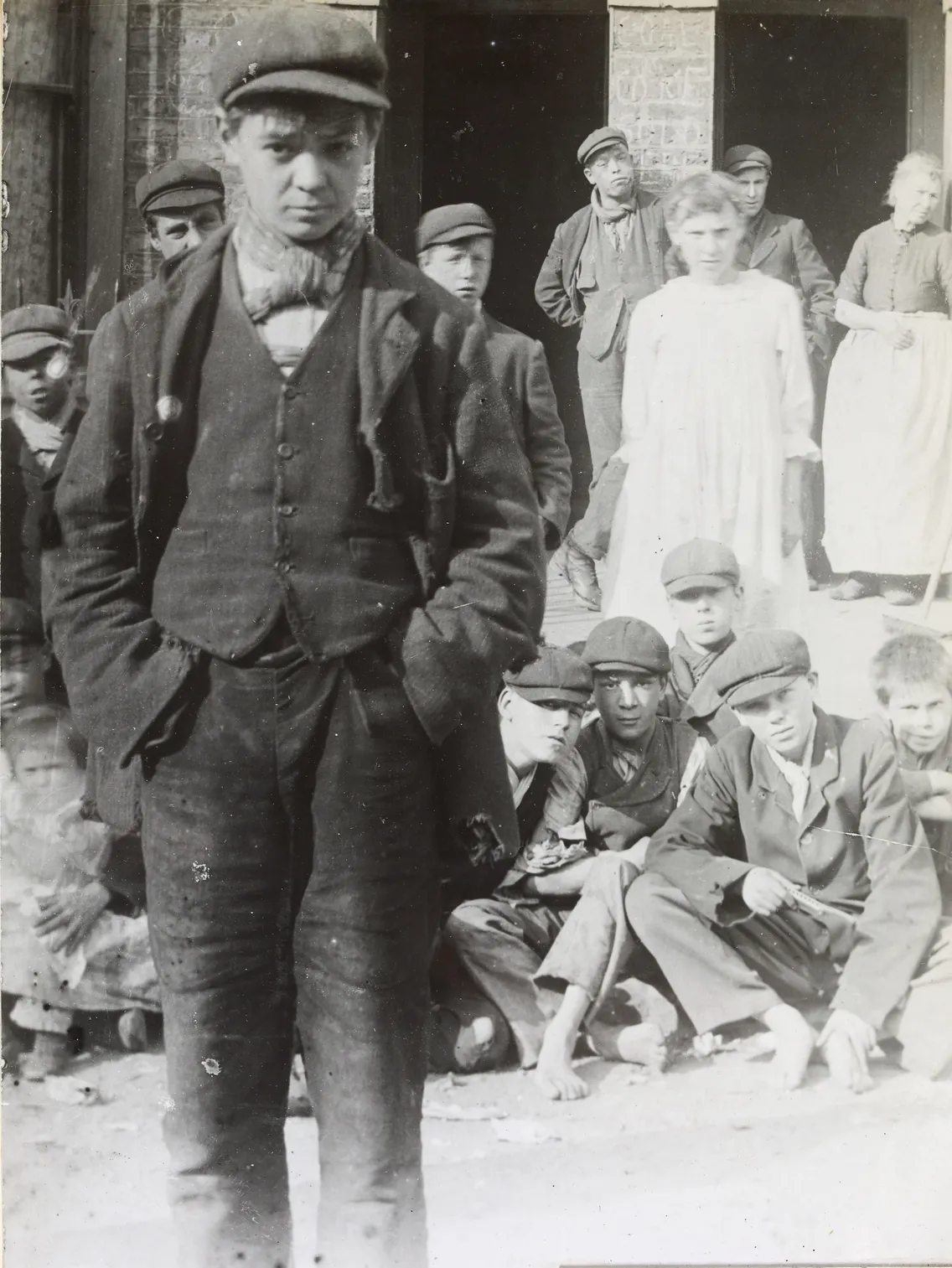

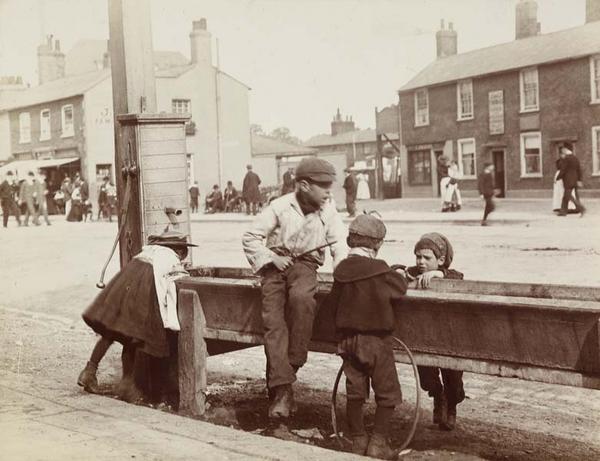

Victorian London was a place of ugly inequality. Many Londoners – men, women and children – lived in extreme poverty, struggling to afford food or a clean, safe home. Life in the government’s workhouses was almost as cruel, with shelter only provided in exchange for gruelling labour.

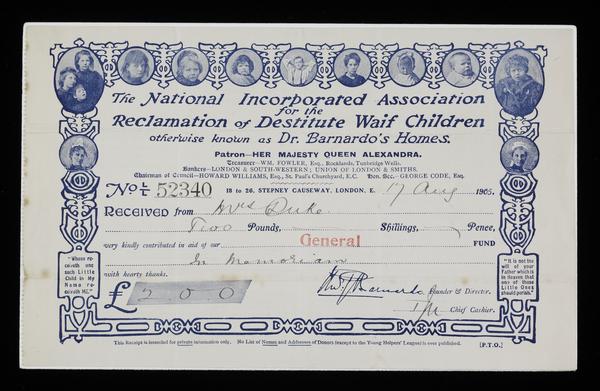

Charitable organisations tried to help. One of the best known was started by Thomas Barnardo, who was motivated by his Christian religion. His many children’s homes offered shelter and training to destitute boys and girls who were either orphans, or whose family couldn’t look after them.

His achievements are celebrated. But some of his methods wouldn’t be accepted today. Along with the government, other charities and churches, Barnardo’s sent thousands of children away, mainly to Canada, where some were abused as cheap child labour. Today, his organisation lives on as Barnardo’s, a charity providing services to children in need.

Who was Thomas Barnardo?

Barnardo was born in Ireland and became passionately religious as a teenager. He first came to London in 1866 to train as a Christian missionary to China.

After witnessing a deadly outbreak of cholera in the East End, he decided to study medicine at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. He never finished his studies, but still adopted the title of doctor.

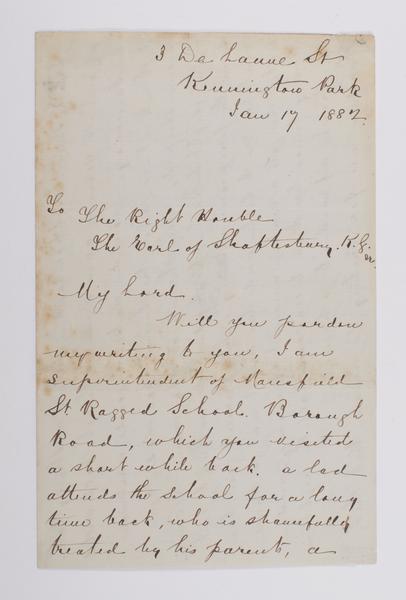

While studying there, he began preaching on the street and taught at a ‘ragged school’ on Ernest Street, giving free education to poor children.

His time in the East End brought him face to face with people living in one of London’s poorest areas. It convinced him to spend his time helping people, especially children, to improve their situation – something he did for the rest of his life.

Why were there so many destitute children in the East End?

The East End was full of cramped, dirty streets and derelict housing. Diseases spread easily. People slept rough in the streets.

In Charles Booth’s groundbreaking 1889 study of poverty in London, large parts of the map for this area are marked in light blue, meaning “poor”, or dark blue, meaning “very poor”.

A combination of factors forced children onto the street. At a time before effective contraception, families could be large. Without regular income, many families struggled to support their children. Children might be sent out to work to help the family. Or they might be forced from home by domestic violence and drinking, or the early death of a parent. Sometimes, life was better on the street.

Barnardo saw this and decided to help. In 1868, he bought two cottages in Limehouse, setting up the East End Juvenile Mission to teach and preach to local children.

Children in a physical education class at Whitechapel Mission – another organisation set up to help the area’s poorest.

Dr Barnardo’s homes

In 1870, Barnardo established the first of his ‘Dr Barnardo’s homes’ on Stepney Causeway.

The first home was for boys only. They were given a place to live and were taught skills – carpentry, metalwork, shoemaking – that might help them get an apprenticeship and earn a living.

In 1871, a boy died after being turned away from one of Barnardo’s homes that was already full. Barnardo vowed it would never happen again. He adopted the slogan ‘No destitute child ever refused admittance’.

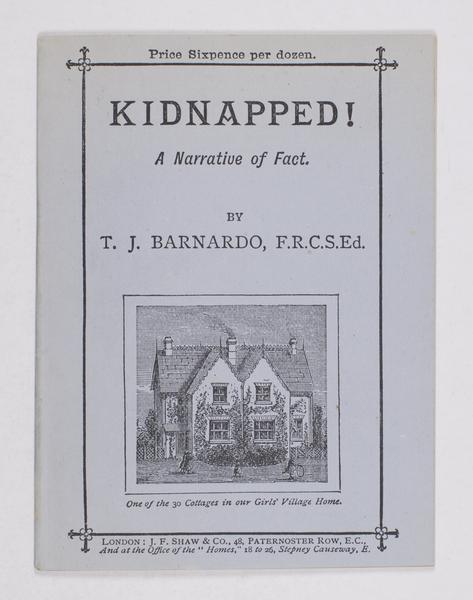

Barnardo’s first home for girls was set up in 1876 in Barkingside, now in the London Borough of Redbridge. It was set up like a village, with small groups of girls living in separate cottages.

He also sent children out to live with families in rural villages, an early version of a foster system.

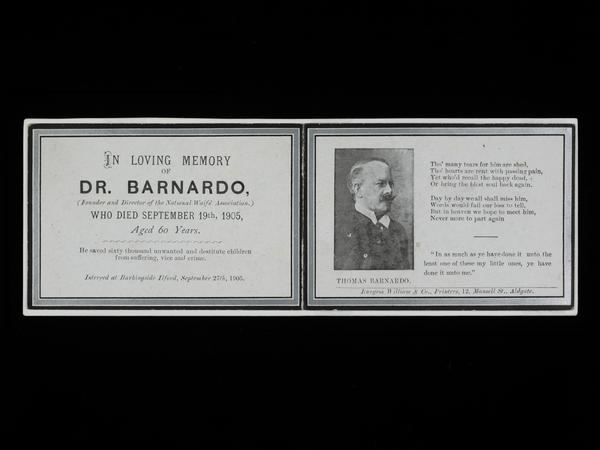

By the time Barnardo died in 1905, he’d placed 4,000 kids with families and his charity ran 96 childrens’ homes, caring for more than 8,500 children.

Barnardo’s sent children abroad

Barnardo worked extremely long hours over decades in the service of children. He was greatly loved in the East End. His funeral procession attracted thousands of working-class Londoners to watch.

But he did face some controversy at the time. Like other charities who were competing to raise funds, he forged ‘before and after’ photos to make children look more ‘ragged’.

And, looking back now, one of Barnardo’s policies that was accepted then can also be criticised.

Barnardo’s homes didn’t take in every child. Some were sent abroad. The first group of boys left for Canada in 1882, with a party of girls going the next year. By 1905, more than 11,000 had been sent away, with most going to Canada.

The aim was to give them a chance of a new life. It was believed the children would have opportunities they’d never have at home.

Barnardo’s organisation wasn’t alone in this. The policy had the support of the government and other charities.

But the children didn’t have a choice and many were falsely told they were orphans. On arrival in Canada, the children were often forced to do hard manual work. Abuse and neglect was widespread.

Britain’s child migrant programme even continued into the 1960s. In total, around 130,000 British children were sent abroad in this way. It’s estimated that 10% of Canada's modern population is descended from children taken from Britain.