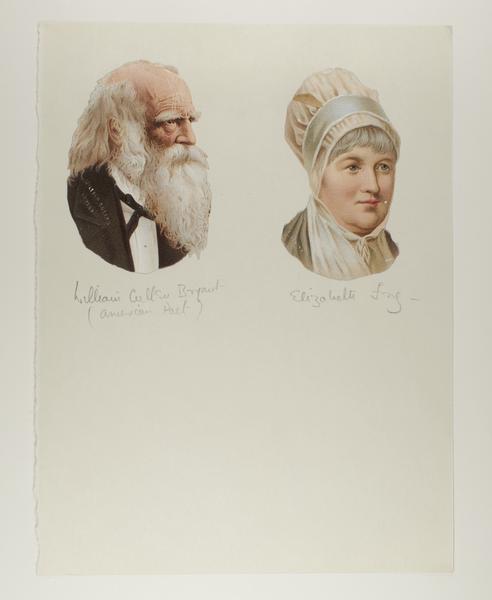

Elizabeth Fry: Pioneering prison reformer

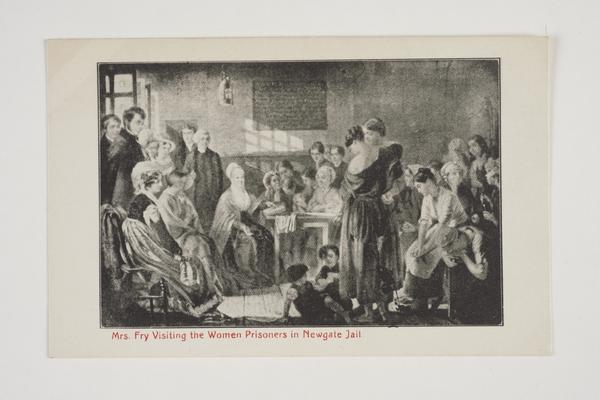

Having witnessed the terrible situation at Newgate Prison, Elizabeth Fry set out to greatly improve the experience of women in the 19th-century prison system.

Newgate Prison

1780–1845

Prison progress

When Elizabeth Fry visited the men and women held at London’s Newgate Prison in 1814, her shock at the terrible conditions there set her on a path of pioneering reform.

She spent the following decades working to improve the experience for women in prisons in this country and abroad. She aimed to help prisoners avoid crime through religious and moral guidance, rather than dishing out cruel and vengeful punishment.

By raising awareness of the poor state of prisons, she helped pass key reforms, including the segregation of men and women prisoners and the introduction of women wardens.

Fry’s work has made her one of the most celebrated British women of the 19th century, alongside the likes of Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole. In the 1900s, the Suffragettes used her story to inspire their members, and she appeared on the £5 note from 2002 to 2016.

When did Fry come to London?

Elizabeth Fry – originally Elizabeth Gurney – was born into a wealthy Quaker family in Norwich in 1780.

She moved to London aged 20 after marrying the banker Richard Fry, a member of the family behind the Fry’s chocolate company. The couple had 11 children.

The Frys lived at St Mildred’s Court in the City of London, then Plashet House in East Ham. After her husband’s bank went bankrupt in 1828, they moved to Upton Lane in West Ham.

A muslin cap from our collection worn by Elizabeth Fry.

Elizabeth Fry was a Quaker

The Quakers are a Christian movement with a strong belief in peace, justice and the equality of all people. Fry’s religion led her to devote her life to helping others.

During her visits to prisons, she was recognised by a simple white muslin cap, an item traditionally worn by Quaker women. We have one in our collection.

Fry’s visit to Newgate Prison

Prison reform had been a Quaker cause for some time. In 1813, a friend suggested that Fry should visit the women’s section of Newgate Prison. At the time, the area outside the prison was London’s main site for public executions.

The jailer there told Fry that the prisoners were dangerous and that Fry shouldn’t go inside. But she insisted.

Fry was appalled at what she found. Hundreds of women prisoners, some joined by their children, were crowded into a few rooms. Some slept on the floor without bedding.

Prisoners awaiting trial were housed alongside those who’d been sentenced to a public execution. There was violence and drunkenness. Fry later described the conditions as a “dreadful scene of misery, riot, idleness and vice of every description”.

Fry continued visiting. She decided to offer the women moral and religious lessons and noticed a positive response from many of the prisoners who wanted to reform. Fry’s empathy for the women inspired her to push for better conditions.

How did Elizabeth Fry change women’s prisons?

The changes inspired by Fry were driven by the idea that kindness, rather than cruelty or neglect, was the right way to reform prisoners.

At Newgate Prison, women matrons, rather than men, were brought in to watch over the women.

Prisoners received a basic education in reading, writing and maths, which could help them after their release. They also had religious classes. Fry was convinced that Christian teachings would benefit the women.

Prisoners were encouraged to sew and knit, skills which would be useful outside prison. They were also allowed to sell the items they made to earn some money. A basket of Fry’s needleworking tools is part of our collection.

In 1818, Fry reflected on the progress made at Newgate: “to my surprise… we have been enabled to demonstrate how much may be done amongst these unhappy outcasts merely by kindness accompanied by instruction and employment.”

Fry’s views on capital punishment

In 1817, Fry was deeply affected by her visits to a female prisoner in Newgate awaiting execution. In her journal she wrote: “this has been a time of deep humiliation to me, this witnessing the effect of the consequences of sin. The poor creature murdered her baby; and how inexpressibly awful now to have her life taken away.”

Many Quakers spoke out publicly against executions – also called capital punishment – believing it conflicted with their religion. Although Fry comforted the condemned, she never openly campaigned for the complete abolition of the death penalty.

Elizabeth Fry became famous for her reforms

Word of her success at Newgate spread. In 1818, Fry became one of the first women to speak to a parliamentary committee.

In 1821, Fry formed the British Society of Ladies for Promoting the Reformation of Female Prisoners, which helped change prisons across the country.

The 1823 Gaols Act used some of her ideas, making it law to have separate areas for men and women in mixed prisons, and to have women guards for women prisoners.

Fry travelled widely, meeting heads of state to share her ideas. She even met Queen Victoria, who gave her money to help with her campaign.

Elizabeth Fry campaigned for an end to slavery

Quakers like Elizabeth Fry played a significant role in the campaign to end the British trade in enslaved people. They were the first religious movement to wholly condemn slavery.

Between 1838 and 1843, Fry actively campaigned for an end to slavery, particularly in the Danish and Dutch colonies in the Caribbean.

When did Elizabeth Fry die?

Fry died of a stroke aged 65 on 13 October 1845. She is buried in the Quaker Gardens in Barking, east London.