21 May 2025 — By Germander Speedwell

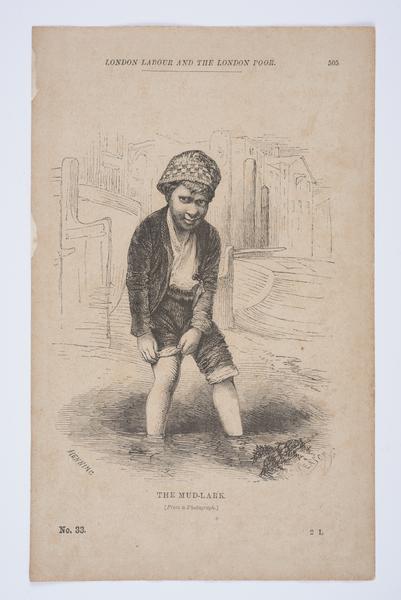

Fired up about pipe finds: A Thames mudlark’s passion

Her walls are lined with the most remarkable decorated clay tobacco pipes from the last 400 years. Mudlark Germander Speedwell shares how these decorated ‘mini sculptures’ found on the Thames foreshore continue to fascinate her.

A masonic pipe design on the foreshore. You can make out symbols like the open book and the all-seeing eye.

“I would never have got into mudlarking if it wasn't for clay tobacco pipes”

Coins, bottles, rings and Roman pottery alone wouldn't have lured me into the mud. But when I learned of the existence of decorated clay pipes, I was captivated. I couldn't believe that these marvellous miniature moulded sculptures – with a seemingly infinite variety of designs – were lying out there, just waiting to be rescued.

Pipe dreams along the foreshore

I owe my discovery of pipes to a fellow called Tom. Long before I knew much about mudlarking, I’d been leading a series of community activities which involved exploring the foreshore. Tom was one of the regular participants, but always ventured much further than the rest of us – past the dry sand and shingle to the uninviting wet mudflats beyond. And he'd return with pipes that left us in awe – decorated with faces, figures, symbols and pictures.

Intrigued, I began to investigate the muddy stretches myself, and sure enough, I started to discover small treasures of my own.

On the Thames foreshore searching for decorated clay pipes.

This was back in 2013 when there were far fewer mudlarks and many more finds. A typical expedition during a decent low tide would always yield 20–30 pipe bowls. Most of them would be plain, but I'd always come back with one new decorated bowl for my collection, sometimes more.

These days, however, I'll be lucky to find five plain pipes, let alone a decorated one. I've compensated by exploring further afield and discovering some lesser-known stretches of foreshore.

Clay pipes are well preserved in the Thames mud until exposed by tidal and wave erosion.

Pipe smoking comes to Britain

Tobacco was introduced to Britain from the New World in the 1580s, during the reign of Elizabeth I. Tobacco smoking took off despite its initial high cost and the efforts of King James I to suppress the habit by imposing exorbitant taxes and publishing anti-smoking literature.

It took centuries for wider public opinion to catch up with him in declaiming smoking a “loathsome” custom, for the habit became widespread and remained popular over the next 300 years.

It also spawned a new trade – pipe making. Clay pipes were made in moulds. They were cheap and disposable, with a short life expectancy. As soon as they were no longer smokable, they were tossed into the rubbish – or rivers – which is why we find so many today. They're often described as the cigarette butts of the past.

This clay pipe almost looks like a discarded cigarette butt on the foreshore.

The Thames foreshore is littered with their remains, mostly fragments of stems. Today these stems are often repurposed creatively in artworks and jewellery, but in the past, people also found alternative uses for them. The Secrets of the Thames exhibition at London Museum Docklands reveals how broken pipe stems were regularly used as wig curlers, and were recommended as improvised catheters or breathing tubes for medical emergencies.

Different styles of tobacco pipes

Most of the early clay pipes were plain, but from the 1740s, decorated bowls started to appear, usually portraying coats-of-arms. Pipes developed into another fashion accessory and new designs flowered in the 1800s.

The range of designs included everything from masonic symbols to famous faces (from war heroes and royalty to entertainers) to depictions of sports and pastimes – reflecting the interests and occupations of the time. In the late 1800s, French pipe makers, in particular, became highly imaginative, playful and even eccentric with their designs.

This dog pipe was made by French pipe makers Dumeril of St Omer, and demonstrates the playfulness of French pipe design.

This French-made novelty dog pipe is a favourite, and it was a memorable find too. It was one of the lowest tides of the year, and I decided to take a chance on a new foreshore. But after over an hour of fruitless searching, I was kicking myself for having wasted such a good tide.

Dejected, I waded out into the clear water, desperate to find anything. And there, several inches below water, I spotted something pipe-shaped, but unusually coloured and curiously ornamented. When I pulled it out and saw the dog, I was overwhelmed with relief – my day hadn't been wasted after all.

This pipe was originally hand-coloured with enamel, as were many of the best French pipes. I've been lucky to find several such ‘French fancies’. A few may have come to London with visitors, but most were probably imports.

“Dutch pipes are known for their high quality and fine finish”

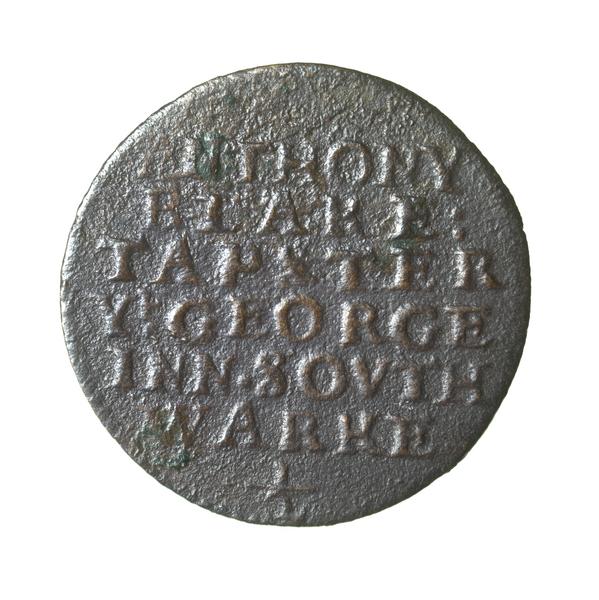

Likewise, Dutch pipes are another highly desirable find in the Thames. Dutch pipes are known for their high quality and fine finish, as well as the fascinating makers' marks on the bottom of their heels.

My favourite heel marks from Dutch pipes I've found include a windmill and a milkmaid. These moulded marks are tiny, only about 5mm across.

Pipes made in London

While some pipes made elsewhere in Britain found their way to the Thames through trade routes, most of the pipes I find are London-made.

Surprisingly, there were only a few industrial-scale pipe makers in London. Most were simply small family businesses – working from home or a workshop, with everyone in the household involved. The women and children usually had their own specialist tasks in the pipe-making process.

Tobacco pipes and social justice

Clay pipe designs were sometimes linked to sociopolitical causes. Enslaved people often worked on tobacco plantations, and the ongoing Secrets of the Thames exhibition features a display of finds associated with the slave trade, including clay pipes.

While one of these pipes bears a design used in the campaign against British trade in enslaved Africans, another is in the form of an African man’s head. There were many such portrayals on pipes. I once found a miniature pipe bowl depicting the head of what looks to be an African boy.

This pipe with the face of an African boy was a remarkable find.

The Speedwell Asylum for Retired Pipes

The Secrets of the Thames exhibition includes a section on mudlarks, showing how they display and use their finds. Displaying my pipes is my second greatest pleasure after finding them.

I've arranged mine in wooden display cases lining the walls of a tiny room. I call this the Speedwell Asylum for Retired Pipes - I consider it a sanctuary, a retirement home for old pipes, where they can reside in comfort among others of their own age.

My best decorated pipes are also displayed on my website, where they are arranged by theme – from faces and heads to animals and plants, to sports and leisure, and much more.

Germander surrounded by her collection of finds.

A river of surprises

The other attraction for me on the foreshore, besides the obvious prospect of finding clay pipes, is the guarantee of surprises. You will rarely find what you’re expecting, but almost always you'll find something unexpected – sometimes amusing, sometimes intriguing, sometimes with a message.

Even if I find nothing, I might bump into a stranger with an interesting story, or a friendly fellow mudlark.

The foreshore is where I go to search for signs, surprises and delights. It has led me to discover hidden sides of history, as well as unexpected human connections.

Germander Speedwell is a London mudlark and describes herself as an obsessive investigator of places, a tireless enquirer of time, and an irrepressible assembler of text.

Please note that you must have a permit from the PLA to go mudlarking on the Thames foreshore.