Who were the River Thames watermen?

For much of London’s history, if you wanted to get somewhere fast, you’d better hail a waterman. For centuries, these sharp-tongued, weather-hardened tradesmen rowed passengers along and across the River Thames.

River Thames

Since at least the 1200s

When the fastest route from A to B was by boat

Long before the capital’s bridges and its modern transport networks were built, Londoners relied on the River Thames to get around.

Watermen were a bit like modern-day taxi drivers, rowing their small boats to pick up and drop off passengers along the river. They were in high demand and, like cabbies with London’s streets, had a deep knowledge of the course of the Thames and its tides.

They were also often portrayed as colourful characters: devious, scrupulous and foul-mouthed.

A trade passed down through families, watermen were just some of the many Londoners who earned their living from the river. But as transport technology and infrastructure developed in the capital in the 1800s, the watermen’s trade declined.

What did watermen do?

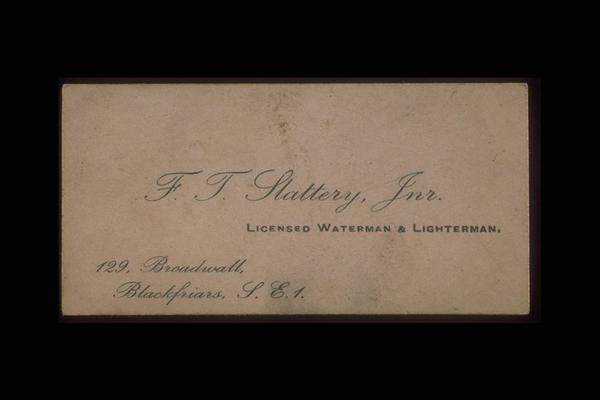

Watermen were responsible for rowing passengers and their luggage across the Thames. They did a similar job on the river to lightermen, who specialised in transporting cargo rather than people. One of the earliest documents describing watermen working on the river dates back to the 1200s.

Until Westminster Bridge opened in 1750, London Bridge was the only crossing in central London. The city’s streets were winding and congested, making travel slow. Hiring a waterman was a fast and popular way of getting across the city.

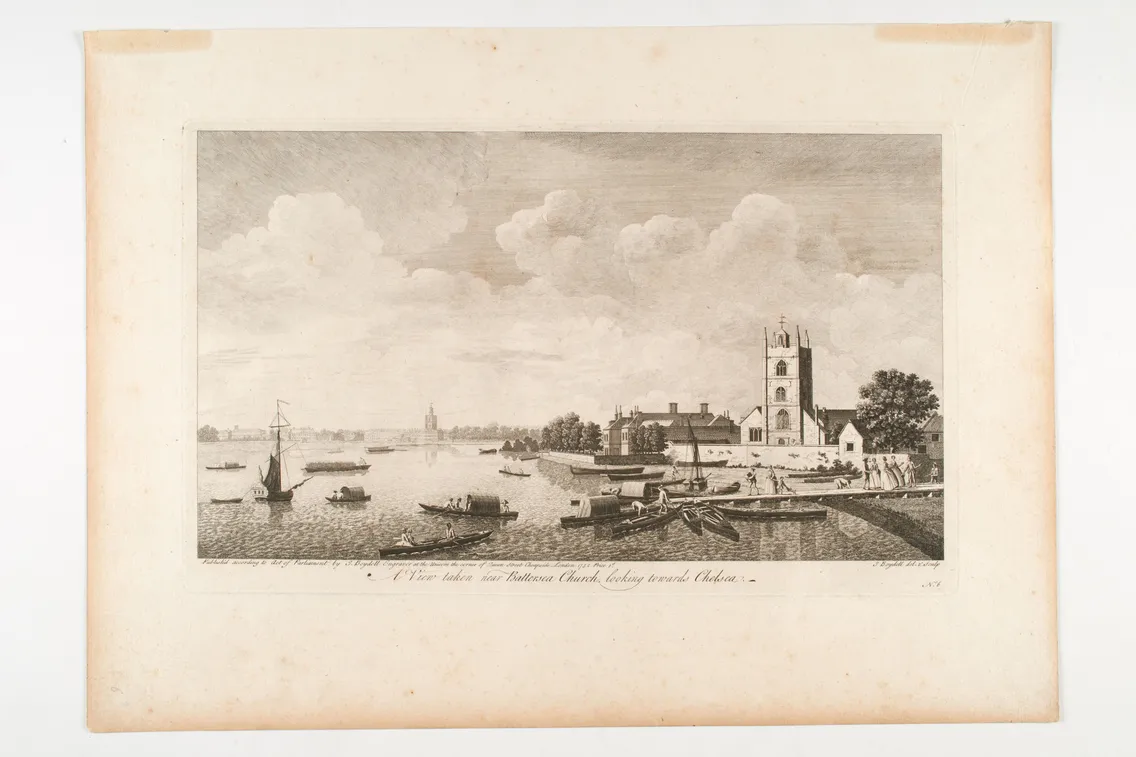

The print below from our collection shows watermen at work in Battersea in 1752, with passengers waiting to board on the right-hand side.

Who hired watermen?

Well-off Londoners employed their own private watermen. At the top of the trade were the royal watermen. They transported members of the royal family along the Thames to the many riverside palaces, such as at the Tower of London, Greenwich and Westminster.

But not all watermen worked for such wealthy customers. Most Londoners could afford to hire a waterman when they needed, making them part of everyday life. To hitch a ride, you’d find a waterman jostling for hire at one of the city’s dozens of river stairs, or ‘watermen’s stairs’, which lined the river.

Many of these slippery descents have since disappeared, with some gobbled up by the building of the Thames embankment in the 1860s. But you can still get a glimpse of the tide sloshing against one in Wapping, near the historic pub the Prospect of Whitby.

They rowed along in skiffs and wherries

Watermen used wooden rowing boats to ferry passengers along the river. For hundreds of years, they mostly used wherries, which were shallow, pointed boats propelled by oars and skulls.

Wooden skiffs were also a common sight on the river from the 19th century. These were shorter and wider than wherries. This one in our collection was built by Cory’s Barge Works in Charlton, Greenwich.

Made in the early 1920s, this skiff is a rare survivor of the 700 skiffs that once worked in the Port of London.

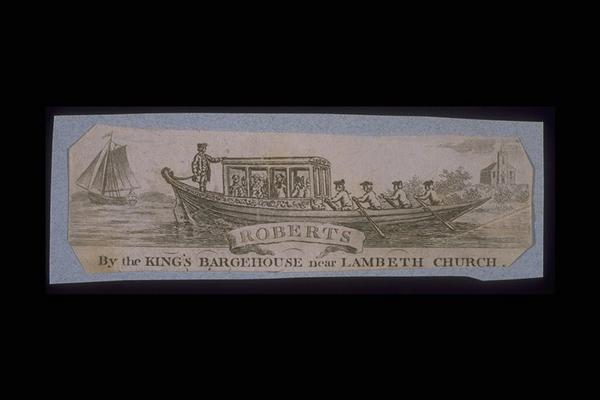

Watermen also used larger boats like barges and tiltboats, named after the extra protection given by the tilt, or canopy, over the passenger.

How were watermen described?

Henry Mayhew, a journalist and social commentator, described watermen in the mid-1800s as “weather-beaten, strong-looking men, and most of them are of, or above, the middle age”. He reported on many of them living close to the river, passing down their trade through the generations to apprenticed sons and relatives.

Watermen had a reputation for their language. “They were hospitable and hearty to another, and to their neighbours on shore,” Mayhew said, “... but often saucy, abusive and even sarcastic.” Their trade relied on their ability to shout and stand out from the crowd. And, similar to Billingsgate fish market merchants, watermen were infamous for their coarse, sometimes vulgar lingo. It was known as ‘water language’.

Doggett’s Coat and Badge race

This red wool uniform is called a Doggett coat. It would have been worn with a silver badge by the winner of the Doggett’s Coat and Badge race. This is an annual four-mile rowing sprint in which apprentice watermen race from London Bridge to Chelsea.

The race was founded in 1715 by actor and theatre manager Thomas Doggett, who wanted to celebrate the accession of George I in 1714.

It’s still going today, making it one of London’s oldest sports events.

What threats did watermen face?

Being a waterman was a dangerous job. You were exposed to bad weather and the powerful tide of the Thames. Many watermen drowned.

During some winters, the Thames would get cold enough to completely freeze over, making it impossible for watermen to work.

Londoners would hold carnivals and markets called frost fairs on the frozen river. Some enterprising watermen set up their own booths on the ice to try and make some money. Others continued to carry passengers across the ice by fitting sledges to their boats.

Watermen also saw the construction of bridges as a threat to their livelihood, since it would allow more passengers to cross the river by foot or by horse.

They protested strongly against the idea of building Westminster Bridge, central London’s second bridge, in the 1660s. The idea was shelved.

Eventually, the bridge was built in the mid-1700s. Watermen were paid compensation for their loss of earnings.

Their trade declined in the 1800s

Most of central London’s bridges were built during the 1800s. And new modes of transport – among them train networks, the London Underground and cab services – made Londoners less reliant on the Thames.

Mayhew recorded the struggles of watermen in the Victorian period: “They are mostly patient, plodding men, enduring poverty heroically, and shrinking far more than many other classes from any application for parish relief”.

“steamers came in, and we were wrecked”

Waterman quoted by Henry Mayhew, 1851

One of the biggest blows to their trade came on the water in the form of the steamboat, first introduced in London in 1815.

Watermen’s boats were no match for the bigger, faster steam engines. Steamboats also offered more comfortable facilities. Day trips to the Kent seaside towns aboard these modern craft became a popular day out for Londoners of all social classes.

Mayhew quoted one waterman saying, “steamers came in, and we were wrecked… We’re beaten by engines and steamings that nobody can well understand.”

Watermen in skiffs row up to a sailing barge in Surrey Docks, 1930.

Are there still watermen today?

The Company of Watermen and Lightermen, a City of London guild founded in 1514, still exists today. They help apprentices to become qualified for work on the river, as well as preserving the traditions of this centuries-old trade.

The role of a Thames waterman has evolved to operating pleasure boats, private charter boats and river bus services. Commuters who prefer travelling on the river over the congested tube and road network can still rely on watermen to get them to their destination.

The royal family has also stuck with tradition by keeping 24 royal watermen for jubilees and other ceremonial events on the river.