What was the Wyatt rebellion of 1554?

In the early months of 1554, Queen Mary I’s plans to marry a future Spanish king caused an uprising led by the landowner Thomas Wyatt.

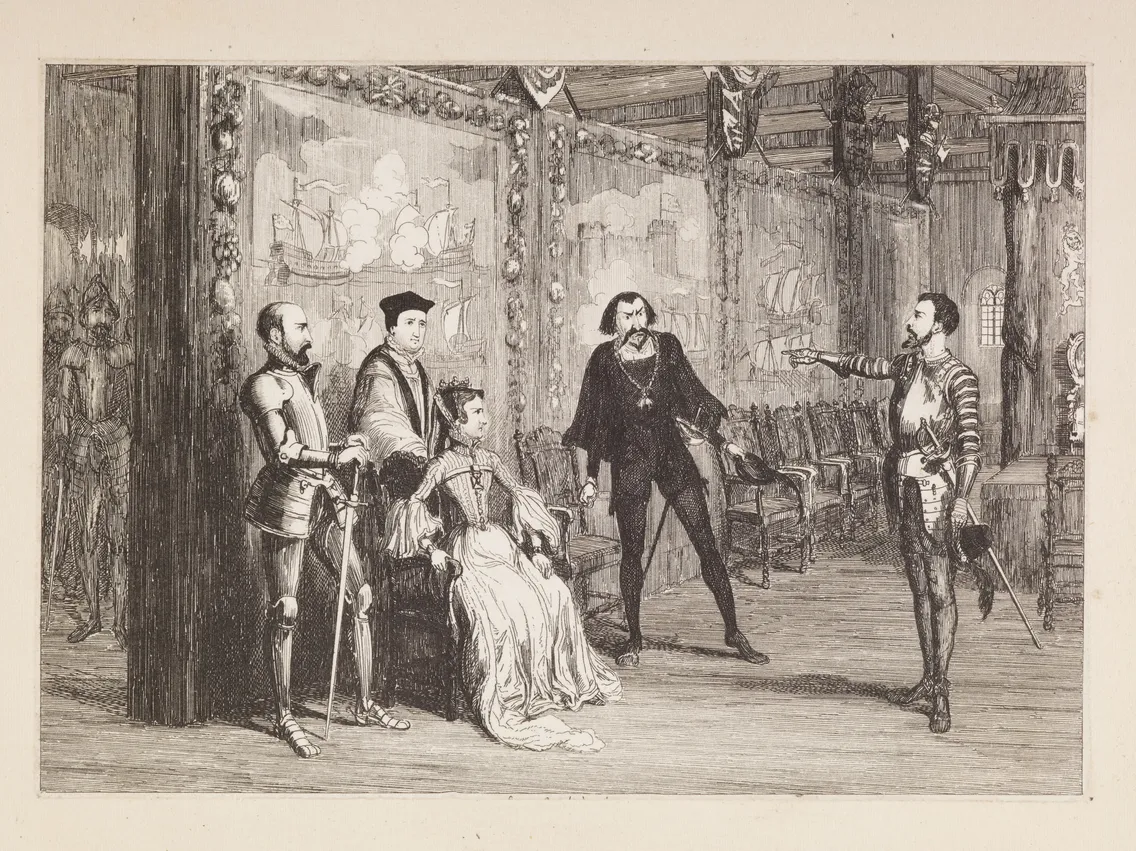

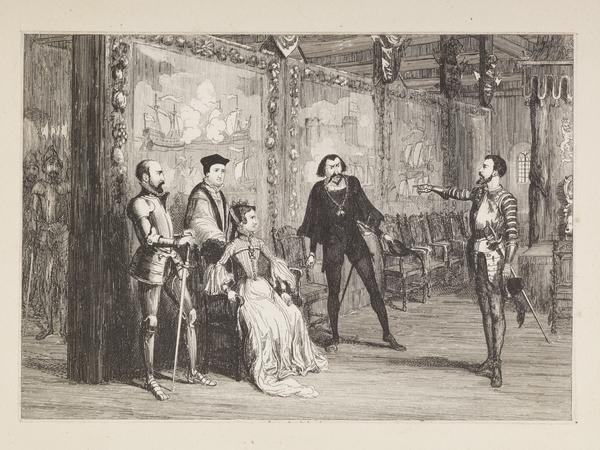

January – February 1554

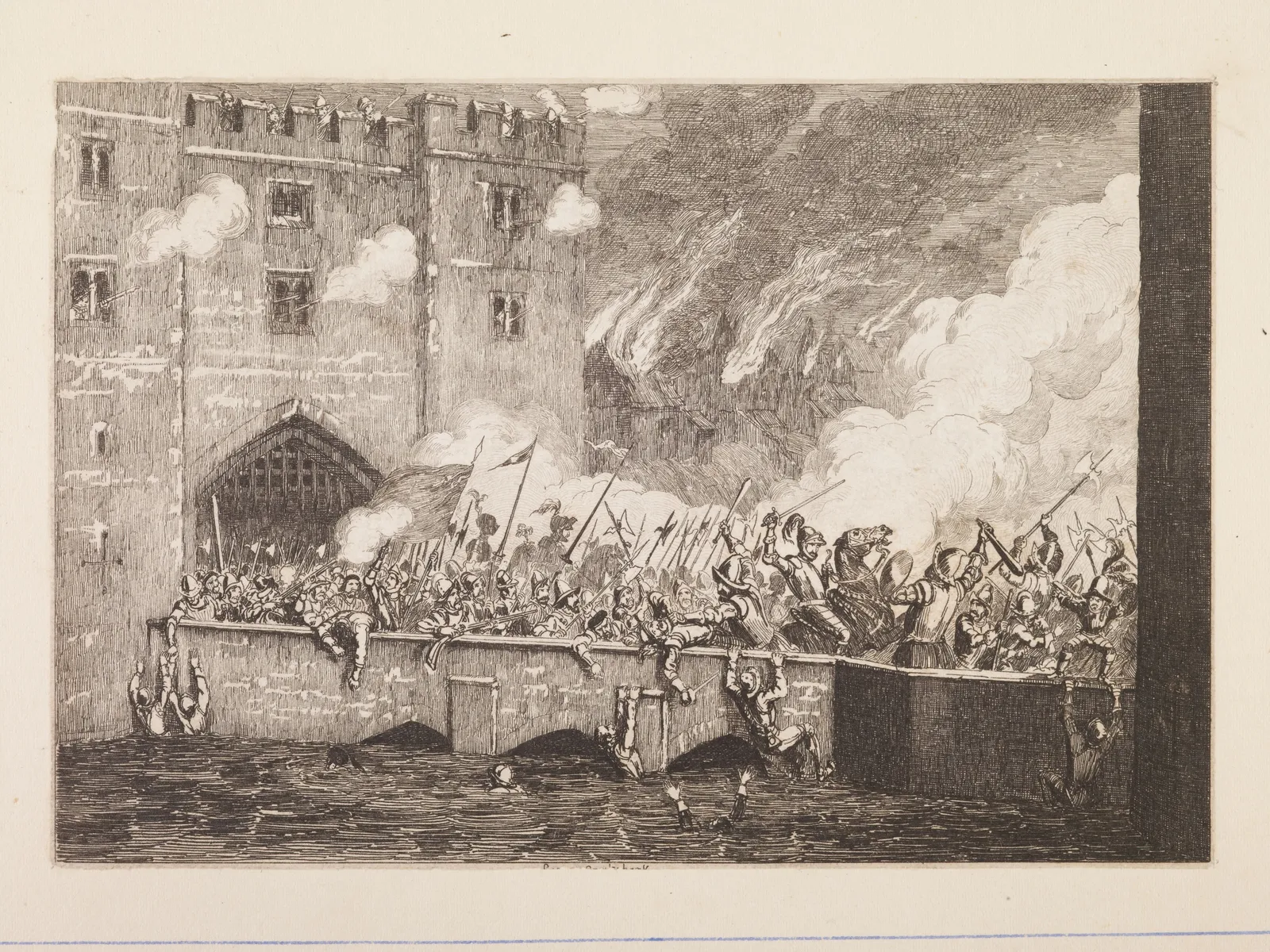

This George Cruikshank illustration shows Wyatt attacking the Tower of London – but in reality, his troops never got that close.

A royal marriage so unpopular it caused a revolt

On 3 February 1554, around 3,000 rebels descended on London, led by a landowner and former soldier called Thomas Wyatt the Younger.

They set their sights on preventing the marriage of Queen Mary I to Philip of Spain, the heir to the Spanish throne. But the rebellion didn’t win the support of Londoners and, on reaching the city walls, Wyatt was forced to surrender.

Despite failing to prevent the so-called ‘Spanish marriage’, the Wyatt rebellion had widespread consequences. People were executed. Protestants were persecuted. And Princess Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth I) was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Who led the Wyatt rebellion?

The Wyatt rebellion was led by a group of prominent men. Some of the group’s leaders were former supporters of King Edward VI, Mary’s half brother, who ruled from 1547 to 1553. One of them, Henry Grey, was the father of Lady Jane Grey, who Edward had made queen for nine short days before Mary took the throne.

The name of the rebellion comes from Thomas Wyatt, one of the largest landowners in Kent and a successful soldier. His father, also named Thomas Wyatt, was a leading noble and poet and a close member of King Henry VIII’s court circle.

Painted portrait of Thomas Wyatt, around 1540–1542.

What were the causes of the Wyatt rebellion?

Historians have argued about the ultimate aims of the rebellion. The driving factor was Mary’s marriage plans.

Some think this was rooted in a fear that Philip of Spain would threaten England’s independence and dominate the country’s politics. Wyatt didn’t want England to turn into “a cockleboat towed by a Spanish galleon”, he reportedly said.

There were also possible religious motivations. Mary and Philip were both Catholic. But under Henry VIII and King Edward VI, England had been transformed into a more Protestant country. The mid-1500s were characterised by conflicts between Catholics and Protestants across much of Europe, known as the Reformation.

This print of Mary I from 1800 describes her as the queen “in whose Reign the Protestants were cruelly Burnt and Persecuted”.

Most of the leading conspirators were Protestants. Wyatt’s rebels also came from a part of Kent that was known as a centre of Protestantism.

Wyatt denied there was a religious motive. The rebellion didn’t use religious ideas in their propaganda. However, this could have been an attempt to get followers to unite under a common cause at a time of great religious division. In Tudor society, politics and religion were tightly entangled.

The rebels were also accused of a plan to kick out Mary in addition to stopping her marriage. Supposedly, this plan involved replacing Mary with her half-sister, Princess Elizabeth. Elizabeth would also marry Edward Courtenay, the English great-grandson of King Edward IV. But there was little evidence to support this accusation.

The rebels were defeated in London

In late January 1554, Wyatt’s force began marching from Kent to London. Along the way, a government army was sent to confront the rebels, but many of their men defected to join Wyatt. By the time Wyatt reached Southwark on 3 February, their numbers had reached around 3,000.

But Wyatt’s army was defeated in London. London Bridge was heavily defended, which forced his troops to cross the river further west at Kingston.

The rebels clashed with royal forces as they moved east through Whitehall and Charing Cross. By the time they’d reached the City walls, their numbers had dwindled to a few hundred. Wyatt surrendered on 7 February.

Why did the Wyatt rebellion fail?

The plotters had actually planned four uprisings in Herefordshire, Devon, Leicester and Kent to converge in London in March 1554. But the government heard about the plan earlier in the year, forcing the conspirators to rush ahead of schedule.

Only Wyatt was successful in raising an army soon enough, so the rebellion didn’t get the widespread momentum it needed.

Most ordinary Londoners didn’t support Wyatt’s army. This made his troops lose determination.

Mary refused to flee London and remained in the city. On 1 February, she made a speech at the Guildhall, an important civic building, that helped rally her citizens in support.

What were the consequences of the Wyatt rebellion?

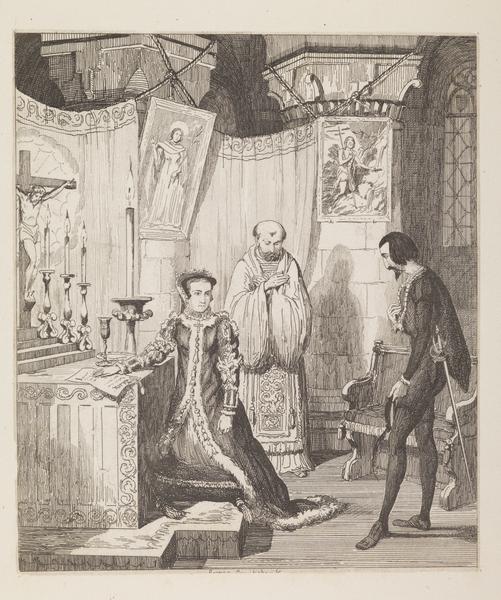

Mary ordered Lady Jane Grey to be executed on 12 February. Grey hadn’t been involved in the rebellion – she’d been imprisoned in the Tower of London since Mary became queen on 19 July 1553.

But her father, Henry Grey, had been involved. And Jane, a pious Protestant, refused Mary’s ultimatum for her to convert to Catholicism. Mary believed Jane would become a figurehead for the rebellion if she wasn’t killed.

Princess Elizabeth was imprisoned in the Tower on 17 March and questioned about her involvement in the rebellion. The queen believed her half-sister would confess under interrogation. But Elizabeth protested her innocence and there wasn’t enough evidence to take her to trial. On 19 May, Elizabeth was moved to house arrest in Oxfordshire.

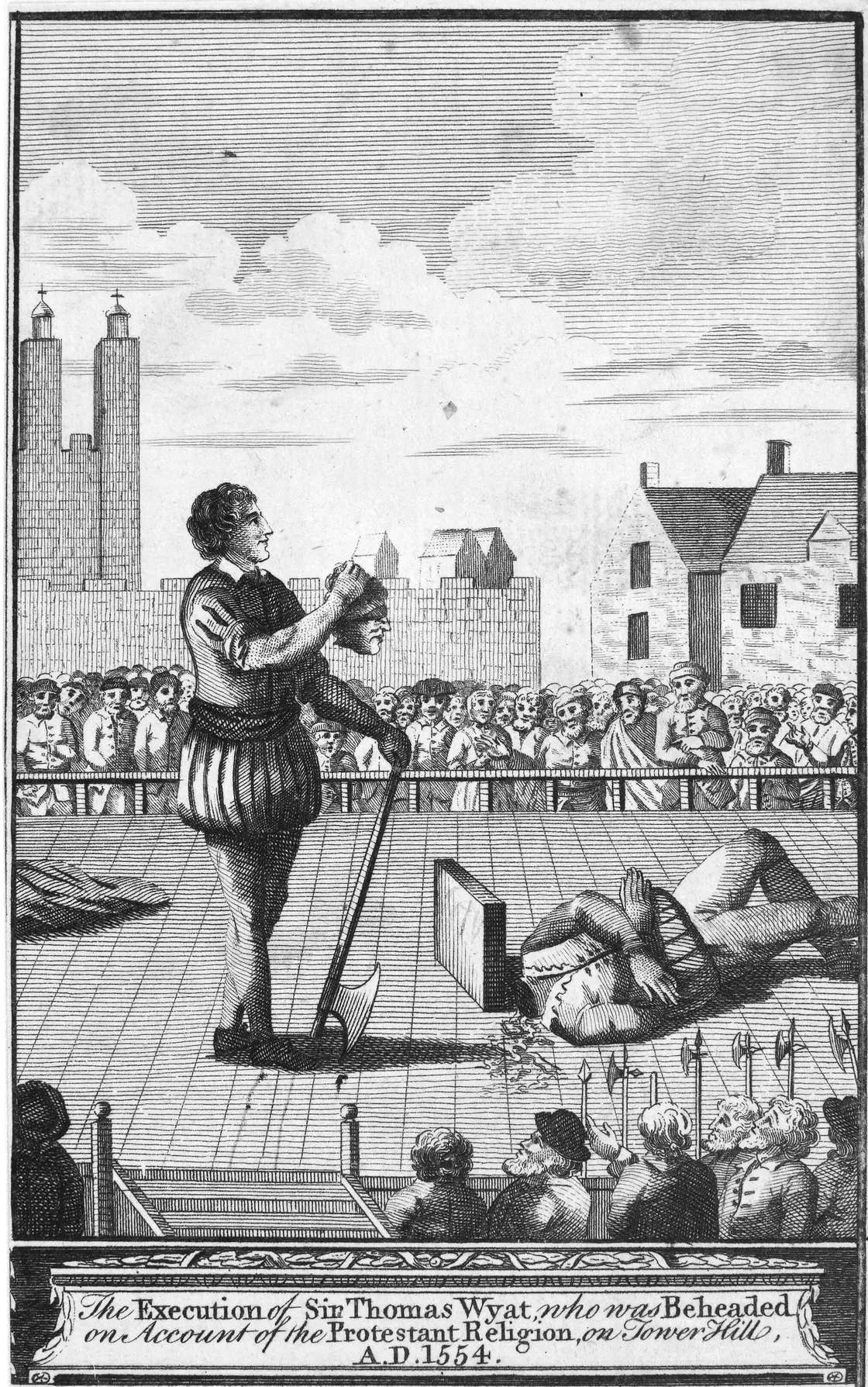

This line engraving shows the execution of Thomas Wyatt on Tower Hill in 1554.

Wyatt was executed on Tower Hill on 11 April 1554. Other rebels, perhaps less than 100, were also killed for their involvmenet. Wyatt denied Elizabeth’s involvement in his final speech. Years later, during Elizabeth’s reign from 1558 to 1603, Wyatt was celebrated as a Protestant martyr.

Mary’s Spanish marriage went ahead on 25 July 1554 at Winchester Cathedral. She set about restoring Catholicism in England and killed hundreds of Protestants in the following few years, earning herself the nickname ‘Bloody Mary’.