A timeline of IRA attacks in London

For three decades, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) attacked London to challenge British control of Northern Ireland. They bombed government buildings, shops, offices, visitor attractions and a pub, killing more than 50 people and spreading terror through the city.

Across London

1973–1998

Damage caused by an IRA bomb detonated at Bishopsgate in 1993.

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

Living with violence

The Troubles is the name given to a complex and bloody conflict which originated in Northern Ireland at the end of the 1960s. The Troubles involved republican and loyalist paramilitaries, the British army, the local police force and political activists.

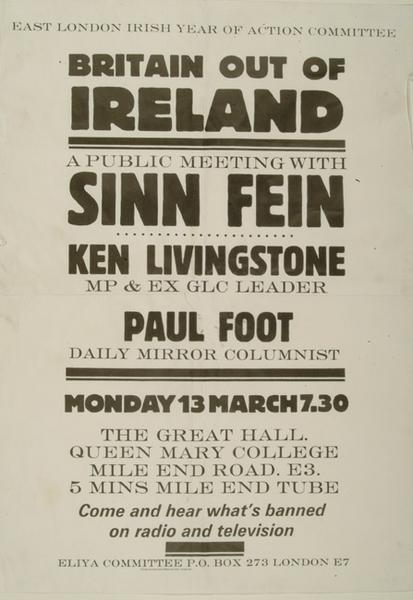

In the 1970s, the violence spread to mainland Britain. In London, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) were the main threat.

Across the IRA’s campaigns on the British mainland from 1973 to 1976 and 1978 to 1982, their attacks included 252 bombs or explosive packages and 19 shootings. In London, at least 50 people died and more than 800 were injured.

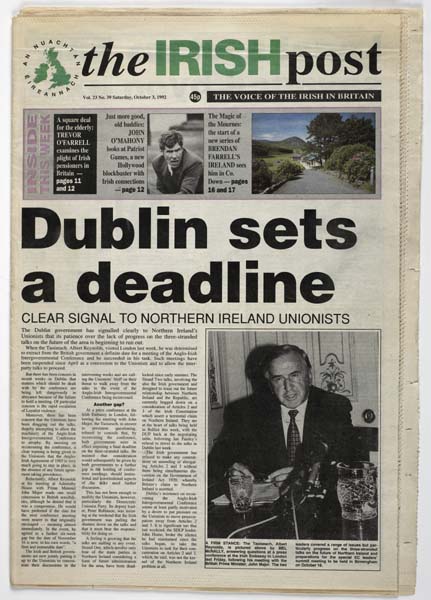

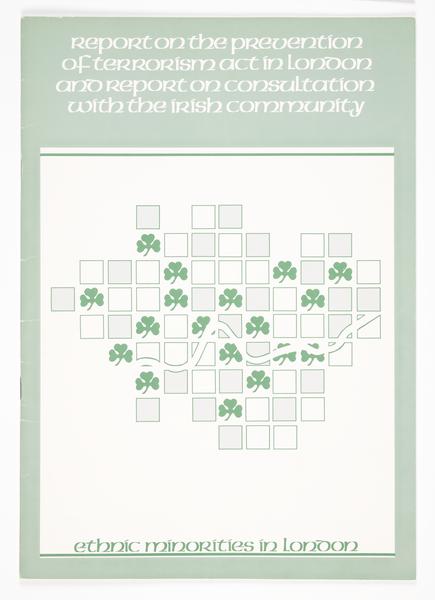

For almost 30 years, Londoners lived with the reality that a bomb might go off at any moment. Irish people in London were treated with suspicion and verbally and physically abused. But daily life continued. In the timeline of events below, we map some of the key dates from the period.

Who were the IRA?

Various groups have called themselves the Irish Republican Army. The first was a paramilitary group created in 1919 to fight for an end to British control of Ireland.

The attacks on the British mainland of the 1970s and 1980s were mainly carried out by a group called the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), which formed in 1969. The group and their supporters viewed their use of violence as a necessary war for Irish independence, not terrorism.

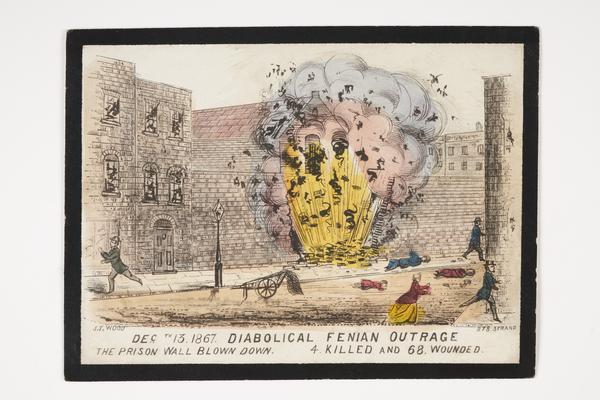

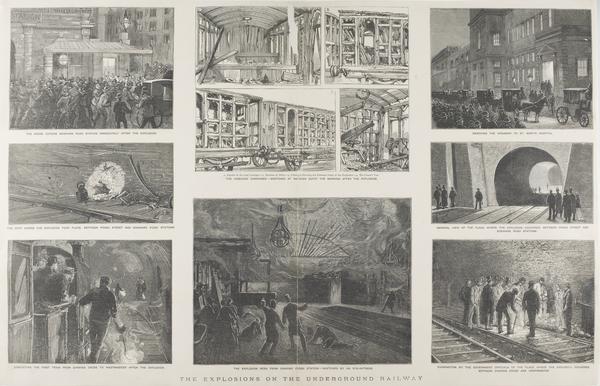

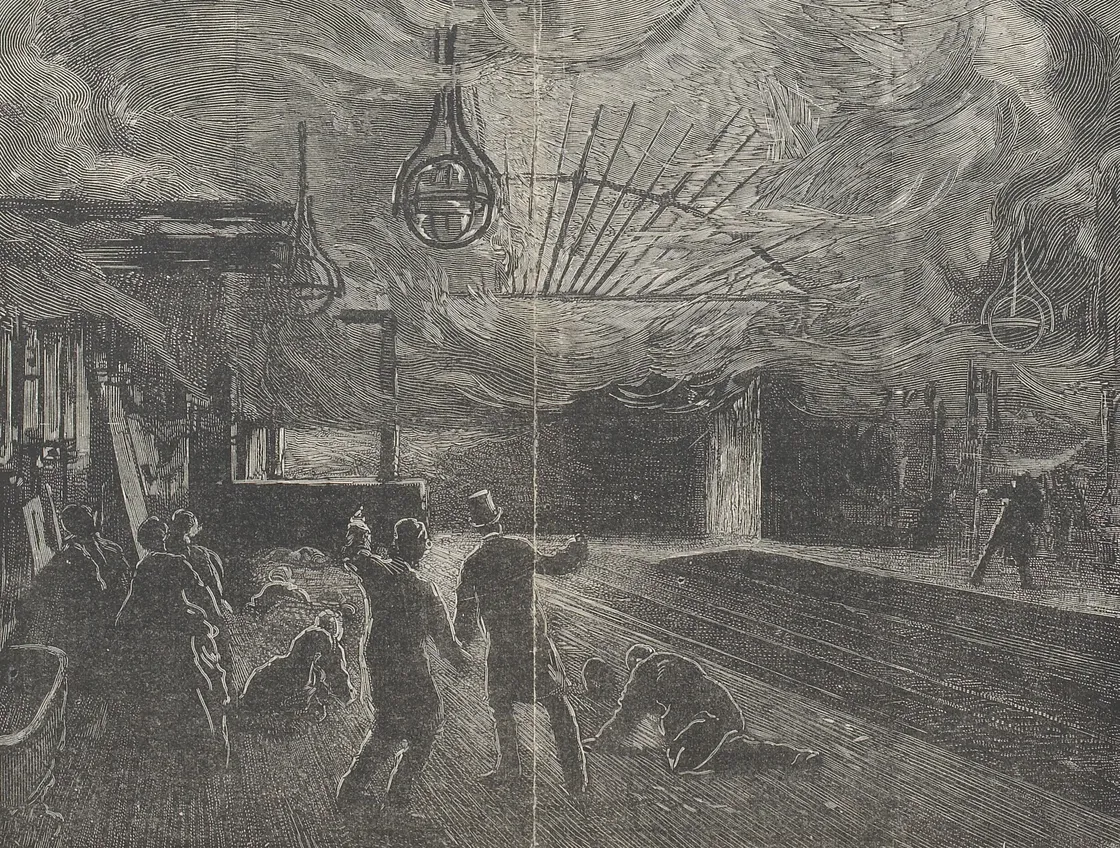

They weren’t the first Irish republican group to target London. A print in our collection from 1867 shows the Irish Republican Brotherhood using dynamite to free some of their members from Clerkenwell Prison. And a cartoon from 1883 shows the explosions on the London Underground that were part of the ‘Fenian dynamite campaign’.

Bombs were detonated by Irish republicans between the Praed Street and Edgware Road underground stations in 1883.

Old Bailey, March 1973

By 1970, Northern Ireland was the only area of Ireland to still be part of the United Kingdom. The IRA wanted to unify the entire island of Ireland as an independent republic.

In Northern Ireland, the IRA attacked British troops and bombed buildings, often accidentally killing civilians.

On 30 January 1972, a day known as Bloody Sunday, the British army shot dead 13 people at a civil rights march in Derry-Londonderry, Northern Ireland. Another person died later of their injuries.

That same year, the IRA began attacks on British soil. They believed this was the most effective way to force the government in London to give up control of Northern Ireland.

The first mainland attacks took place in London on 8 March 1973. Two car bombs exploded – one outside the Old Bailey, London’s historic criminal court, and another at an army recruiting office on Great Scotland Yard, Westminster. One person was killed and 243 were injured.

In the following year, bombs were detonated at the Tower of London, Houses of Parliament, Selfridges and many other locations.

Balcombe Street siege, December 1975

The IRA used small groups called cells to plan and carry out attacks. These cells operated independently to reduce their chance of being detected.

In 1975, four men behind a series of deadly attacks became infamous as the ‘Balcombe Street gang’ after their dramatic capture.

On 6 December, they carried out a drive-by shooting, firing at Scott’s restaurant in Mayfair, then a favourite of Prince Charles (now King Charles III). With the police chasing them, the men fled to a flat on Balcombe Street, Marylebone, and took the couple living there hostage.

After a tense six-day siege by police, the four men finally surrendered, releasing the hostages.

Hyde Park and Regent’s Park, July 1982

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher – who the IRA tried to assassinate in 1984 – thought the solution to the Troubles was tougher security against republican paramilitaries, not negotiation.

In 1981, she refused the demands of IRA members hunger-striking in prison, allowing Bobby Sands and nine others to starve to death rather than recognising them as political prisoners.

On 20 July 1982, two bombs exploded in London parks within two hours of each other. They killed 11 people and injured many more – one of the worst attacks of the period.

The Regent’s Park bomb, 1982.

The first, a nail bomb, targeted British soldiers of the Household Cavalry as they rode through Hyde Park to Horse Guards Parade. The second targeted soldiers from the Royal Green Jackets performing at the Regent’s Park bandstand.

One horse died in the first explosion, and another six had to be shot due to their injuries. The distressing photos of the dead horses were printed in newspapers the next day. Sefton, a horse who suffered life-threatening injuries but survived against the odds and returned to duty, became a national hero.

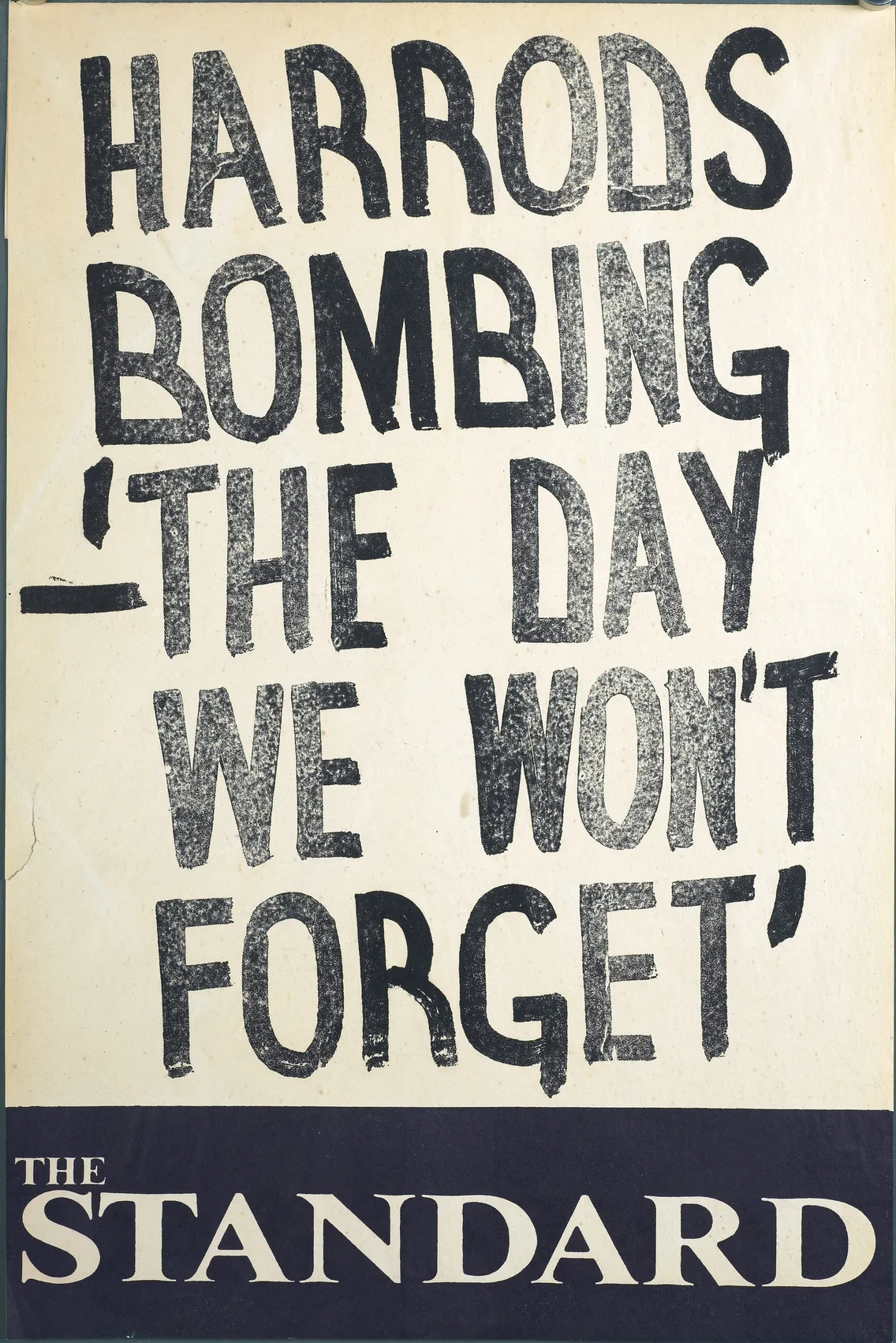

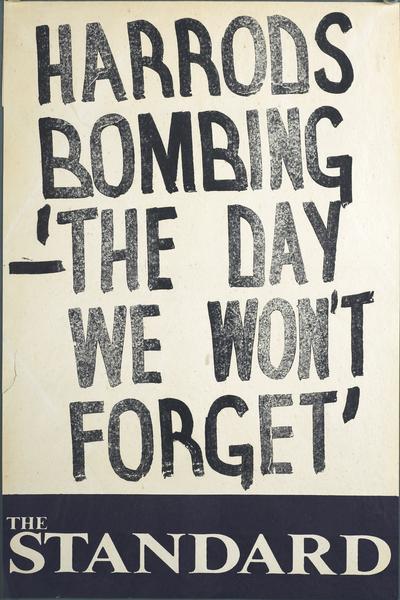

Harrods, 17 December 1983

During the pre-Christmas shopping period, an IRA bomb was detonated at London’s most famous department store, Harrods, in Knightsbridge. It killed six people and injured 90 more.

10 Downing Street, 7 February 1991

On 7 February 1991, three homemade mortar shells were fired from a van towards 10 Downing Street, where Prime Minister John Major was meeting his war cabinet. One shell exploded in the garden, but nobody was injured. The IRA used mortar shells again in 1994 in an attack on Heathrow airport.

Baltic Exchange, 10 April 1992

In the 1990s, the City – London’s financial centre – became a major target for the IRA.

A bomb exploded at the historic Baltic Exchange trading hall in 1992, killing three people, including a 15-year-old girl. It was the biggest bomb detonated on mainland Britain since the Second World War (1939–1945). The exchange was badly damaged and later demolished. The Gherkin now stands in its place.

Bishopsgate, 24 April 1993

A photograph in our collection shows the moments after a one-tonne bomb hidden in a lorry exploded outside the HSBC headquarters in Bishopsgate, in the City of London.

The IRA often phoned in warnings about the bombs they’d planted to minimise civilian deaths. The police received coded warnings about the Bishopsgate bomb. Still, one person was killed – a news photographer who rushed to the scene – and 44 were injured. The medieval St Ethelsburga’s church was also destroyed.

The bomb was a turning point in the City of London’s approach to security. It led to the creation of the ‘Ring of Steel’. The City was fortified with checkpoints, armed police and an innovative CCTV network. This included the first Automatic Number Plate Reading (ANPR) system, which was used to identify suspect vehicles.

Docklands, 9 February 1996

In 1994, the IRA declared a ceasefire with the “complete cessation of military operations” as political leaders worked towards peace.

But the peace process began to falter, and on 9 February 1996, the Provisional IRA announced they were ending their ceasefire. One hour later, they detonated a bomb left in a lorry at South Quay in Docklands. Two people died and 40 were injured.

Another ceasefire was declared on 20 July 1997, and peace talks resumed. In 1998, the Belfast Agreement, also known as the Good Friday Agreement, was signed. This political solution to the conflict was confirmed by two referendums – one in Northern Ireland, the other in the Republic of Ireland – finally bringing the Troubles to an end.

Buildings in Docklands damaged by an IRA bomb in 1996.