The sinking of the Princess Alice

When the pleasure cruiser Princess Alice collided with a huge steamship, 650 people died in the sewage-filled Thames. It was an immense tragedy that filled the newspapers and stunned Londoners.

River Thames, near Woolwich

3 September 1878

The Thames’ worst catastrophe

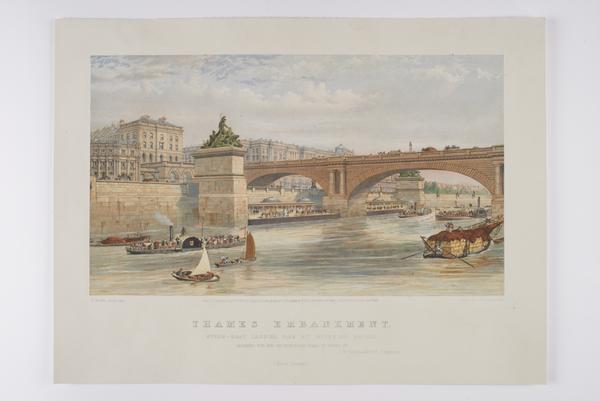

By the 19th century, huge steam ships chugged along the River Thames carrying goods between London’s docks and every corner of the world.

Meanwhile, pleasure-seekers crammed aboard paddle steamers for day trips to the growing coastal resorts in Kent and Essex.

The Princess Alice was one of these paddle steamers. On 3 September 1878, it was packed with couples and families headed back from a day trip to the Kent coast. Near Woolwich, it collided with a much larger cargo ship and sank quickly. Hundreds drowned in sewage-filled water, polluted by a nearby pumping station.

Around 650 people died. The newspapers followed the tragedy closely – as did stunned Londoners. Though incidents like the 1989 Marchioness disaster followed, the sinking of the Princess Alice remains the worst ever single loss of life in the Thames.

Where was the Princess Alice going?

The Princess Alice was returning from Sheerness on the Kent coast, heavily laden with passengers. Many had enjoyed a pleasant day out at the Rosherville pleasure garden in Gravesend.

By the mid-19th century, millions of Londoners enjoyed regular day trips to coastal towns like Margate and Ramsgate.

The Princess Alice was owned by the London Steamboat Company, which had a fleet of 70 steamers by 1876. Named after Queen Victoria’s third child, the Princess Alice was powered by two paddle wheels mounted on its sides.

Who was on board?

We don’t know the exact number of people onboard, as the vessels that used the Thames weren’t required to record their passengers.

However, we know that the passengers were a mix of men, women and children, mainly from middle and working-class backgrounds.

“dead bodies are continually being washed ashore”

The Times, 5 September 1878

How did the Princess Alice sink?

It was 7.40pm on a clear evening, just around dusk. The Princess Alice was entering Gallions Reach, near Woolwich, when the small steamer was struck by a huge cargo steamship, the Bywell Castle.

The collision split the Princess Alice in half – like “cutting a piece of bread with a knife”, according to one witness. The Princess Alice sank within five minutes, leaving 600–700 people in the river.

Despite the millions of passengers journeying up and down the Thames each year, the regulation of traffic on the river and passenger safety were not considered issues of high priority.

An article in The Times newspaper described the tragedy as an accident waiting to happen: “The wonder, indeed, is, not that such an accident should have happened, but rather that it should have been so long escaped.” Sources told the paper “Collisions in the Thames… are of incessant occurrence.”

Recovering bodies from the Thames.

Why did so many people die?

Roughly 650 people died in total. We can’t be sure of the exact number because there wasn’t a list of the people onboard.

There were rescue attempts by the crew of the Bywell Castle and other passing craft. But the Thames’ currents are strong. Most of the passengers drowned before they were reached.

At the time, the water was full of raw sewage, released by nearby pumping stations. The foul water worsened the passengers’ ordeal and hampered the rescuers.

Mortuaries were set up the next day, mainly at Woolwich dockyard where the bodies were laid out to be identified. Our collection includes the burial certificate of Elizabeth Mary Chapman, who died aged just eight.

On 5 September 1878, two days after the sinking, The Times reported, “Along the whole course of the river from Limehouse to Erith, dead bodies are continually being washed ashore.”

“a crowd of sightseers began tearing pieces off as souvenirs”

What was the reaction to the sinking?

The scale of the disaster, its location and the deaths of so many young families sent a shockwave through the capital. Huge crowds assembled outside the offices of the London Steamboat Company and the temporary mortuaries.

The Illustrated London News and other London papers shared the story and any news in detail, giving vivid accounts of narrow escapes and fortunate rescues.

Bodies were buried at Woolwich Cemetery.

The intense media reporting stirred up a frenzy of interest, in the same way that news spread via social media can today. When the remains of the wreck were hauled onto the riverside at Woolwich several days after the sinking, a crowd of sightseers began tearing pieces off as souvenirs.

Some of those souvenirs are now part of our collection. One is a ship in a bottle made from a fragment of the wreck.

The Port of London Authority Archive, which is managed by London Museum, contains an original brass nameplate from the wreck, reading “Princess Alice”.

Funds were raised to erect a memorial to the casualties of the tragedy in Woolwich Cemetery, which still stands today.

There was a coroner’s inquest and a separate inquiry by the Board of Trade, but they reached different verdicts about who was at fault. As the captain of the Princess Alice had died in the incident, the trial lacked crucial evidence of what happened onboard.