Picture Post believed in the power of photography

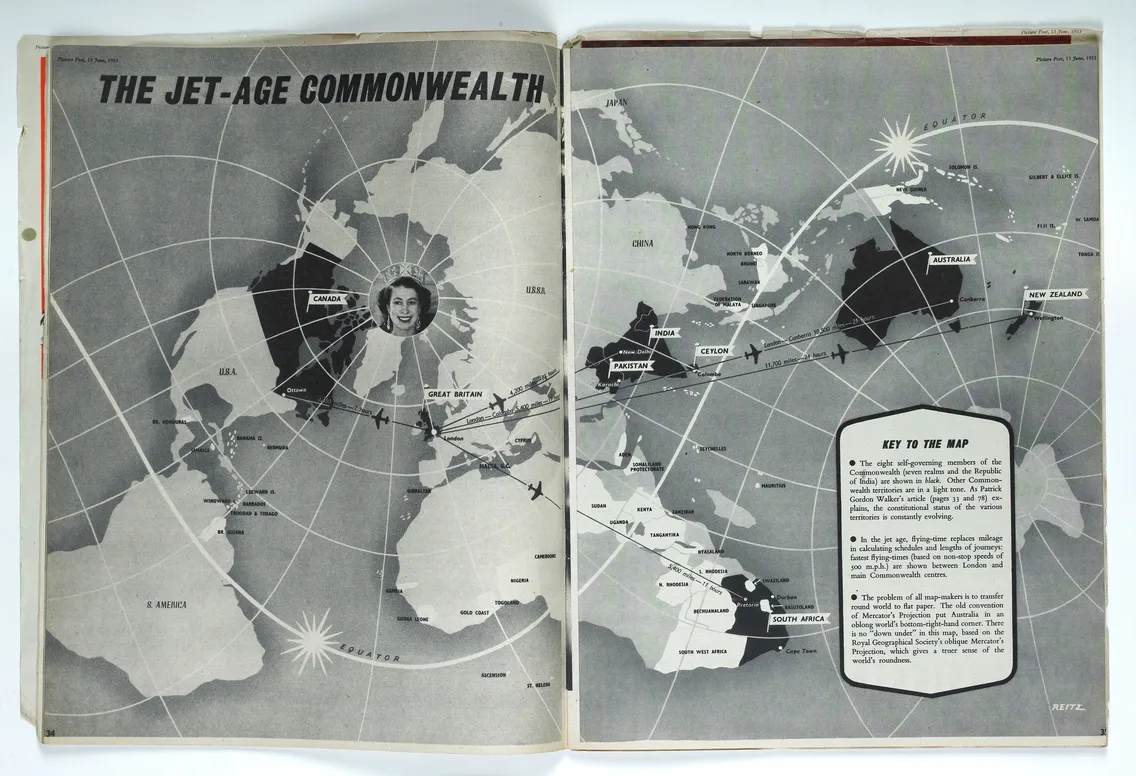

Published in London, this photojournalism magazine put images front and centre in its reporting on current affairs, at home and abroad. It was a hugely influential publication and was a vehicle for change during and after the Second World War.

City of London

1938–1957

Photo essays on the ordinary and extraordinary

Picture Post was co-founded by Hungarian photojournalist Stefan Lorant and British publisher Edward Hulton. It first hit the newsstands in October 1938, one year before the outbreak of the Second World War (1939–1945).

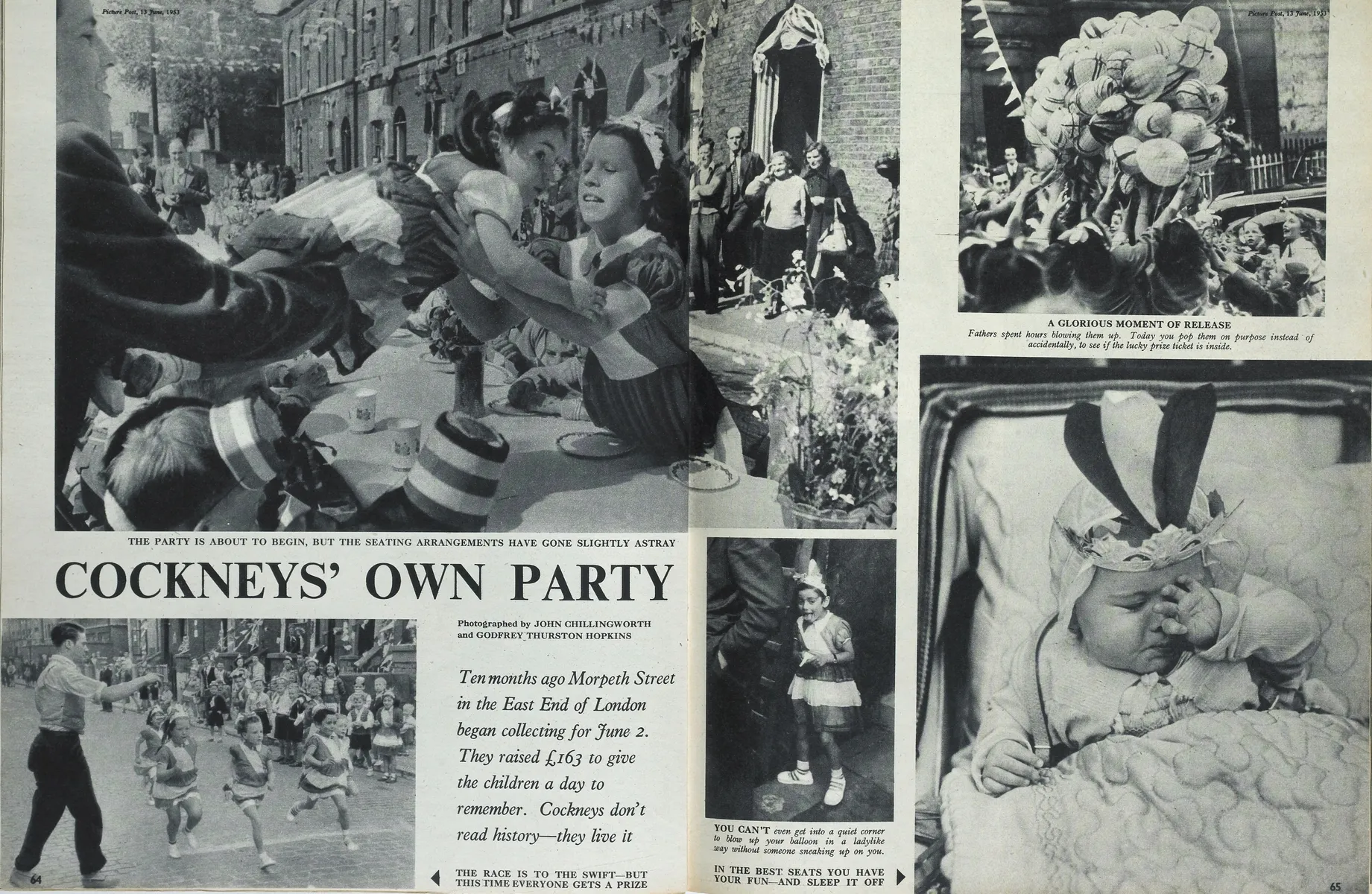

A left-wing magazine with a social conscience, Picture Post presented photo essays on daily life and major news stories around the world. Photographs weren’t just used to illustrate the story – they were the story.

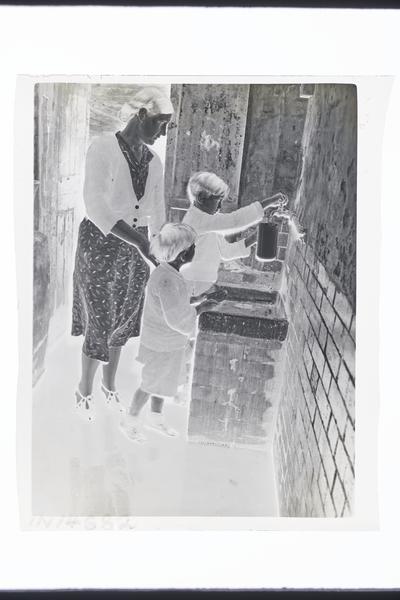

Its photographers and journalists never shied away from tough subjects like poverty, prisons, racism and unemployment. The magazine showed what life was really like in vivid black and white.

Stefan Lorant helped bring photojournalism to Britain

Lorant was born in Budapest, in what was then Austria-Hungary, to a Jewish family. In his late teens, he moved to Germany to establish himself as a filmmaker and a journalist. He was the editor of one of Germany’s most important picture magazines, Munich Illustrated Press.

In 1933, a few weeks after Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, Lorant was detained in Munich. His diaries from his time in prison record a longing for London: “My happiest days were those I was able to spend in London. I love the City, Oxford Street, Pall Mall and the Strand. I love the little restaurants in Soho and the endless streets of the East End. I love the docks and the wide spaces of the ports.”

After six months, Lorant was released. He fled to London, and in 1934, he became the editor of Weekly Illustrated magazine.

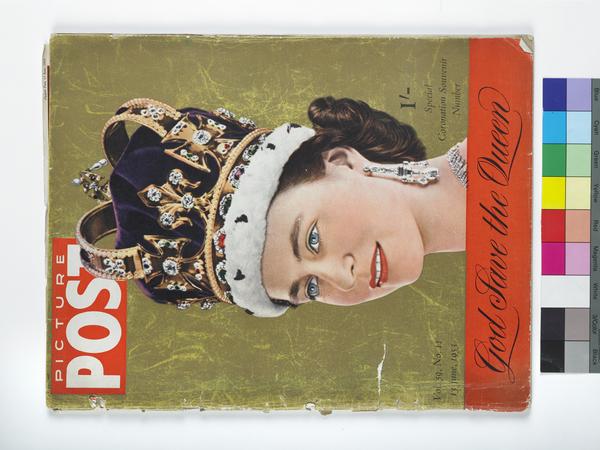

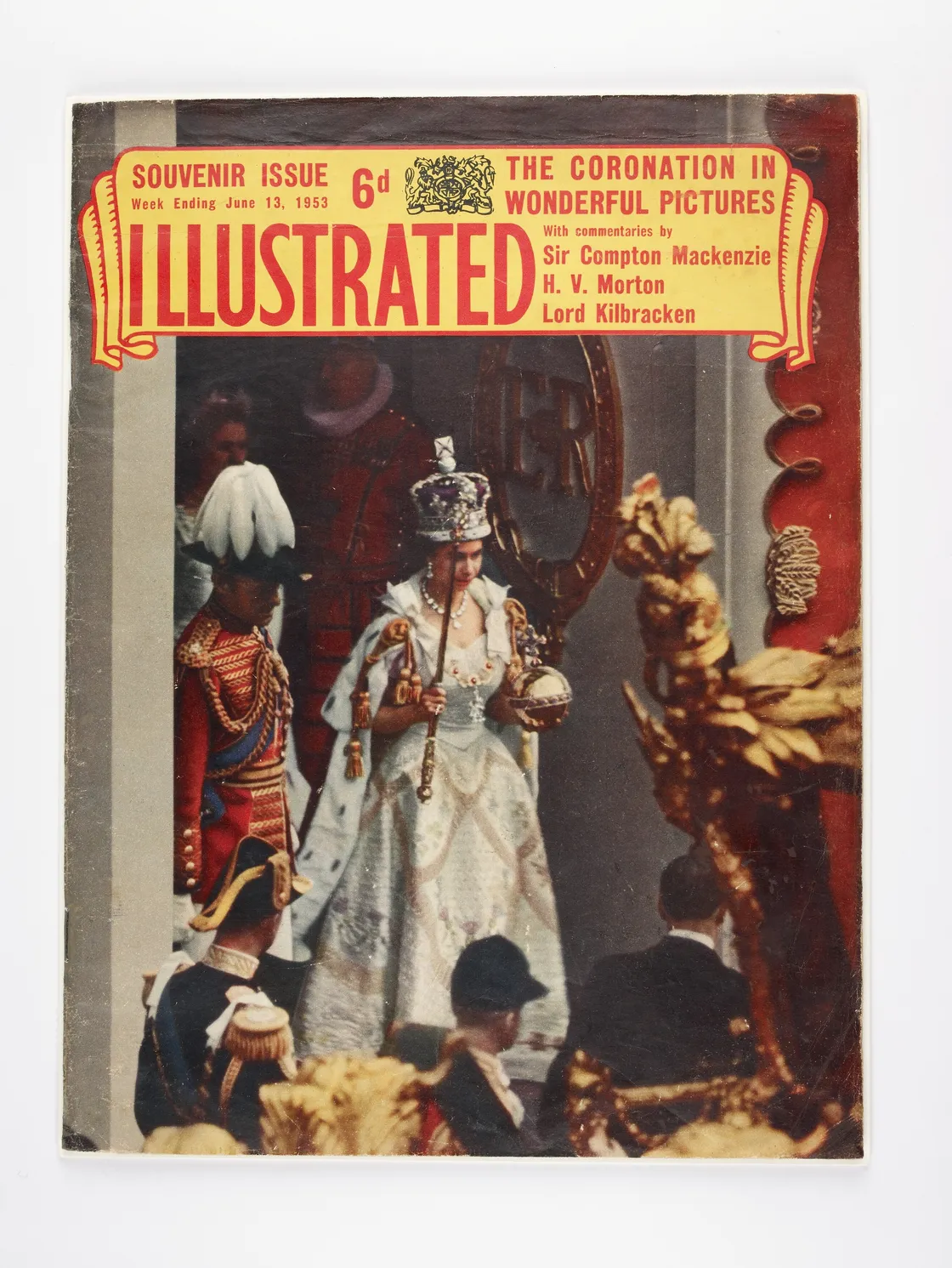

A souvenir special edition of the weekly magazine Illustrated in 1953, formerly Weekly Illustrated.

Under his direction, Weekly Illustrated became the first British magazine to use European ideas of photo reporting, in which news stories were told through placing contrasting photographs close together.

In 1937, he founded Lilliput, a small-format monthly magazine which mixed photography with short stories, art and cartoons. German-born, London-based photographer Bill Brandt produced photo essays for both publications.

Picture Post was born

In 1938, the publisher Edward Hulton bought Liliput and commissioned Lorant to produce a new magazine: Picture Post. It was published on Salisbury Square, close to Fleet Street in the City of London. Fleet Street is famous for its long association with journalism and the printing industry.

“the magazine was for ‘the common man, the worker and the intelligentsia’”

The magazine delved into all sorts of topics from the very first issue, spanning art, current affairs, international news and more. Picture Post used plain language to appeal to many people. In Lorant’s words, the magazine was for “the common man, the worker and the intelligentsia”.

Its coverage was international, but it also captured British life in vivid detail. Lorant was able to see the eccentricities and familiarities of life here with fresh eyes. Things ordinary Brits encountered every day, but hadn’t ever properly thought about.

The magazine made an instant impact

The magazine was an immediate success. After just four months, it was selling 1,350,000 copies a week.

Before TVs became widely available and affordable in the 1960s, people relied on either the radio or the text-heavy newspapers for their news. Picture Post emphasised images over words, providing readers with a new way of seeing and learning about the world around them.

New photographers and camera technologies

The magazine showcased emerging photographers, many of whom were refugees fleeing war and persecution in mainland Europe, just like Lorant.

Lorant championed work by photographers he’d previously worked with in Germany, such as Kurt Hutton (born Kurt Huebschmann) and Felix H Man (born Hans Bauman). Gerti Deutsch, born in Austria to Jewish parents, became the magazine’s first woman photographer and staffer in 1938.

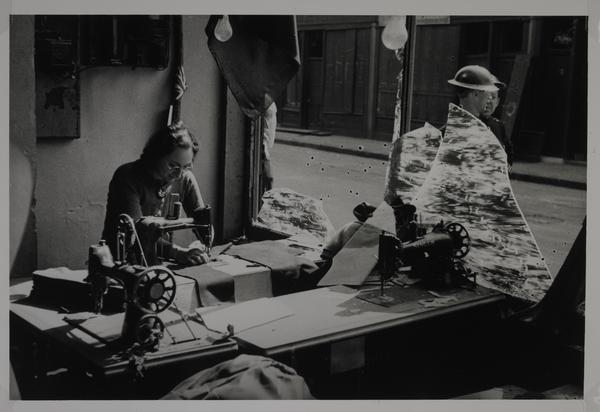

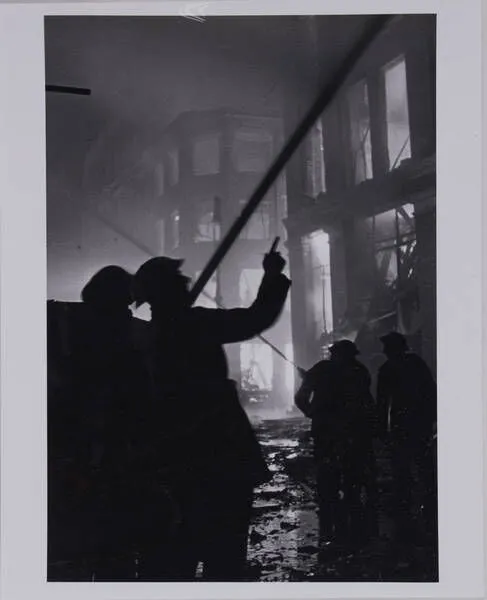

A new generation of English photographers were also associated with the magazine, such as Haywood Magee and Bert Hardy. Hardy was the first photographer to be credited by name in the magazine. His picture essays of Glasgow and London during the Blitz were among Picture Post’s most famous spreads. Some of these images are now in our collection.

Bert Hardy was the first photographer to receive a picture credit in Picture Post for his photo essay Fire Fighters!, an acknowledgement of his skill and bravery taking these photographs.

The magazine also championed new developments in camera technology. Photographers shot on compact cameras made by companies like Leica, which allowed them to quickly capture ordinary lives in fleeting, candid moments.

“putting the picture first”

Tom Hopkinson became the new editor

In 1940, Lorant left England and moved to America. He passed on the stewardship of Picture Post to his assistant, Tom Hopkinson, who he’d also worked with on both Weekly Illustrated and Lilliput.

In his new role, Hopkinson encouraged journalists to collaborate with photographers on new projects, always “putting the picture first”. The magazine continued to report on the Second World War with essays by Humphrey Spender and Leonard McCombe. Hopkinson also helped to publicise the horror of the Nazi’s treatment of Jewish people.

After the war, articles began to consider how the country could recover after the war. It argued for the creation of the National Health Service and a far-reaching welfare state. People even gave the magazine credit for the Labour Party’s landslide victory in 1945.

The beginning of the end for Picture Post

Hopkinson continued to cover international stories. In 1950, he commissioned Bert Hardy and James Cameron to report on the war in Korea. The story focused on harsh treatment of political prisoners by the South Koreans. But it outraged the publisher Hulton. He condemned the report as “communist propaganda” and promptly fired Hopkinson from his post as editor.

Hopkinson’s departure marked the beginning of the end for Picture Post. The magazine continued to attract talented writers, including women such as Grace Robertson and Elizabeth Chat. But its editorial direction was weak, and leant heavier on celebrities and bland stories. Gone were its golden years of socially conscious journalism. Picture Post had lost its focus.

The magazine’s reputation and readership declined. It closed on 1 June 1957.