How the Norman conquest changed London

The Norman invasion of England in 1066 is one of the most famous moments in the nation’s history. In the 100 years that followed, Norman rule in London brought new castles, new people and a new language.

Cities of London and Westminster

1066–1100

Westminster Abbey, where William I was crowned, appears on the Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered record of the Norman conquest made in the 11th century.

New king, new city?

The success of William the Conqueror and his Norman invaders at Hastings in 1066 echoed far beyond the battlefield.

London surrendered soon after the Battle of Hastings, and change came quickly.

French became the language of the elite. The Normans built castles, including the first Tower of London. And settlers arrived from France, including Jewish people from Rouen who founded a community here.

Who were the Normans?

The Normans were actually Vikings to begin with. These Scandinavians were seen by others as ‘north men’, which is where their name comes from.

Around 900 CE, much like other Scandinavians did in Britain, they switched from raiding the coast of northern France to settling there.

They took control of the region that became known as Normandy, winning recognition from the French kings. The Normans adopted the French language and the Christian religion.

How was London conquered?

In 1066, the Normans killed the English King Harold at the Battle of Hastings in the south of England. The remaining English leaders retreated to London, which was well defended.

William’s army headed for the city and made it successfully to Southwark. But with Londoners defending the city’s walls on the north bank of the River Thames, the Normans were unable to hold London Bridge. This was the only river crossing near the city at that time. Deciding against another assault, the Normans burned Southwark, then went up-river to cross the Thames further west.

In the end, the remaining English forces surrendered in Berkhamsted, north-west of the modern city border.

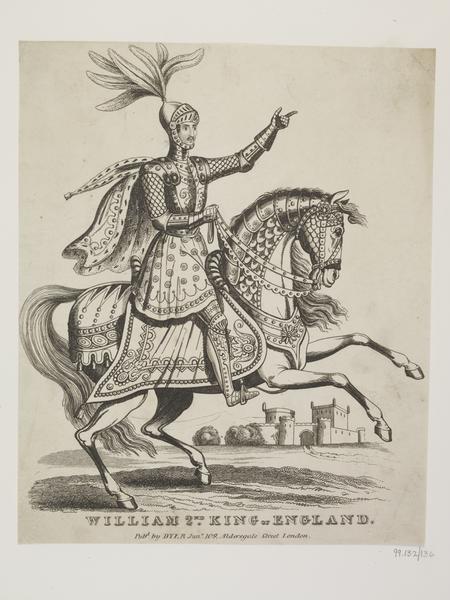

A new royal line

William the Conqueror, also called William I, was crowned at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day – 25 December 1066. He was followed on the throne by his sons, William II and Henry I.

After Henry I’s death in 1135, there was a power struggle between Matilda, his daughter and chosen heir, and Stephen, his nephew. Stephen’s death in 1154 marks the end of the Norman period.

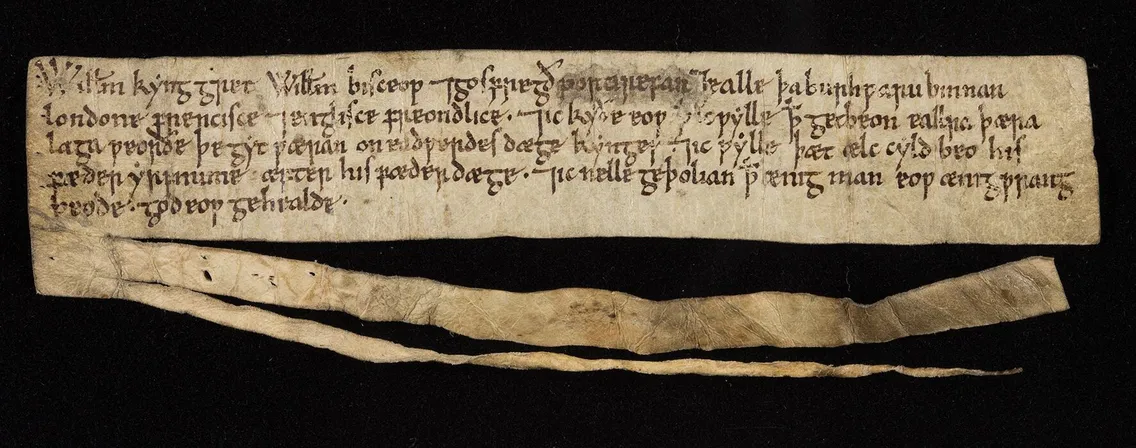

“I will not allow any man to do you any wrong”

William I’s London charter

Running the city

After London’s surrender, William I installed a supporter of his, Geoffrey de Mandeville, as portreeve, a role that put him in charge of the city.

William wrote a letter to him, the bishop of London and the people of the city: “I intend you to have all the rights in law you had in the days of King Edward… and I will not allow any man to do you any wrong. God keep you.”

With this message, William was allowing Londoners to continue governing their city themselves. But the Normans and their allies were firmly in power, with the king giving out land as the reward for loyalty.

Westminster became even more important

William I’s coronation at Westminster Abbey in 1066 may have been the first in a tradition that stretches up to the modern day.

At that time, Westminster was a separate entity, connected to the City of London by the Strand. Previous kings had based themselves there and built a number of royal buildings, including the medieval Palace of Westminster.

Westminster Hall was built by William II between 1097 and 1099. It’s the only part of the old palace to have survived to today.

In the 1100s, Westminster gradually replaced Winchester as the centre for government. Powerful nobles built their homes nearby, ensuring they were close to the monarch and his decision-making.

London’s new Norman castles

The Normans built castles across England and Wales to cement their control.

In London, they were particularly cautious about the city’s independent spirit. The Normans built three castles – more than anywhere else in Britain. These were “a defence against the inconstancy of the numerous and hostile inhabitants”, explained the Norman priest William of Poitiers.

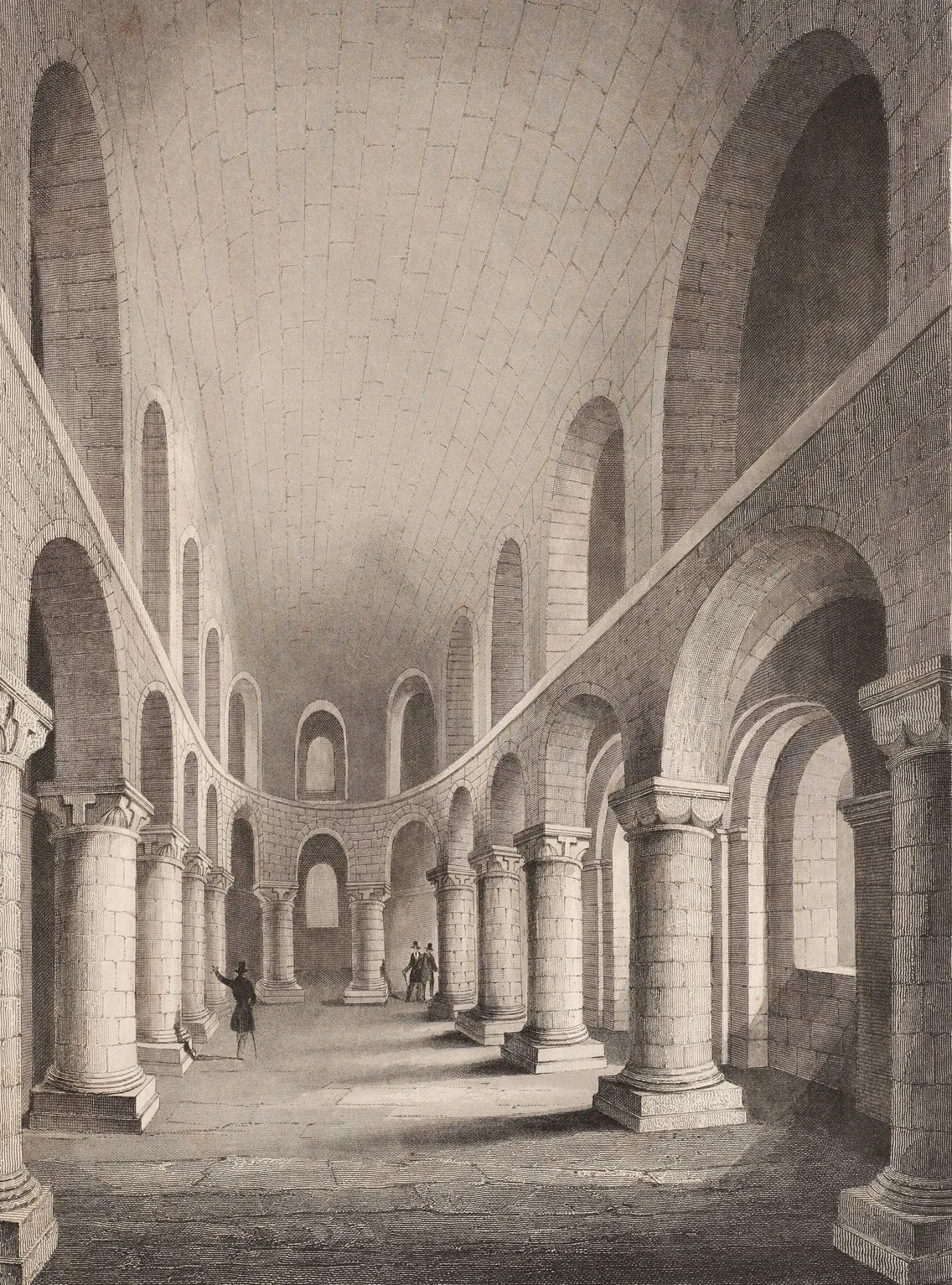

The most famous castle, and the only survivor, is the White Tower at the heart of the Tower of London.

The White Tower was a royal castle. The other two castles belonged to Norman lords. Baynard’s Castle stood at Blackfriars, on the north bank of the River Thames. It was rebuilt several times, but was finally destroyed for good in the Great Fire of 1666.

Montfichet’s Tower was a fortress on Ludgate Hill, close to the site of St Paul’s Cathedral. It seems to have been in ruins by 1278.

The White Tower was a major landmark in the medieval city.

The beginnings of a new St Paul’s

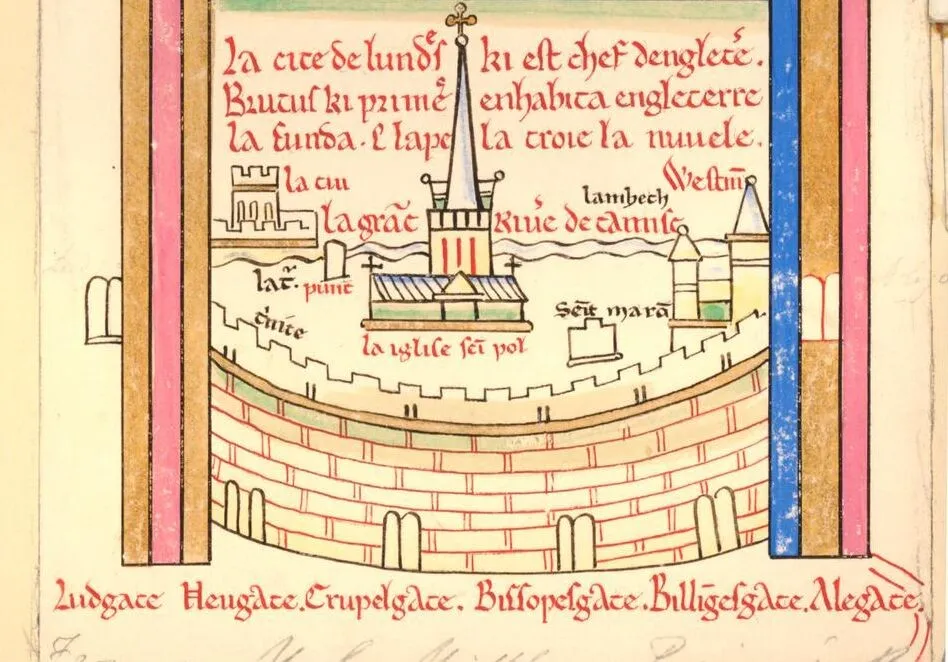

When a fire destroyed St Paul’s Cathedral in 1087, the rebuilding began with royal support. Construction dragged on for centuries and significant changes were still being made until the mid-1300s. This building is what we call Old St Paul’s, given that it was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.

London also gained several monasteries and churches under the Normans. Fragments survive, with probably the best visible section at St Bartholomew’s priory in Smithfield.

St Paul’s Cathedral appears in a manuscript from 1236 by the monk Matthew Paris, as does London’s wall.

City government

London was divided into wards. Each ward had a local forum to discuss local matters, called a wardmote.

In 1132, Henry I gave the city the right to choose its own sheriffs, the city’s most important officials at the time. It wasn’t until 1189 that the city chose its first lord mayor.

The Norman conquest brought new people

London’s population grew under the Normans from around 10,000 in 1085 to over 30,000 by 1200.

Unfortunately, the city wasn’t included in William I’s famous Domesday Book, a survey of landholders across the country.

Still, we know that settlers from Normandy, especially the cities of Rouen and Caen, followed the conquering force to England. A writer in the 1100s described how they “settled in London as the foremost town in England, because it was more suited to commerce and better stored with the goods in which they were accustomed to trade”.

London-born Thomas Becket, who played a major part in the capital’s story, was the son of a textile merchant from Rouen. Becket is famous for being murdered in 1170 while he was the archbishop of Canterbury. He was adopted as one of London’s patron saints.

Significantly, some of those who came from Rouen were Jewish. Rouen had an existing Jewish community, and they were invited to England by William I. By 1130, Old Jewry, near the Guildhall, was the centre of a Jewish community. The number of Jews in London was somewhere between 450 and 1,000, the largest group in England.

This lamp from the 1100s may have been used in a Jewish family’s home, where it would have been lit on Friday evenings and on the eve of festivals.

Jews ‘belonged’ to the king under English law. He protected them, but he also controlled and exploited them. At the time, Jews were forbidden by law from working in trade or industry. Instead, they worked as moneylenders.

Some Jews became rich. That caused jealousy. There was antisemitic rioting and killings in the 1100s and 1200s, and in 1290, the king expelled Jews from England.

A new language

No, English people didn’t all switch to speaking French. But over time, there was a noticeable combination of Old English and French. The result is called Middle English.

After the Normans arrived, French was used in government and was spoken by rich landowners, the majority of whom were Norman. Latin was used by the church and to record laws. English was spoken by ordinary people.

This divide shows up today in the way we talk about food. ‘Pork’, ‘beef’ and ‘mutton’ all come from French. ‘Pig’, ‘cow’ and ‘sheep’ are all from Old English.

Our legal words like ‘justice’, ‘court’ and ‘evidence’ are all from French.