Greenwich Park: Where time begins

Greenwich Park’s story is packed with royal drama, scientific breakthroughs and deer that have called it home since Tudor times.

Greenwich

Since 1433

Invention, adventure and discovery

Ever wondered where time begins? Right here in Greenwich Park.

This large green space in south-east London isn't just another pretty park. It’s the home of Greenwich Mean Time, the exact point where east meets west and a starting point for time zones around the world.

The significance of Greenwich Park dates back millennia. Findings of a Roman temple complex and an early medieval cemetery show continuous human settlement in Greenwich Park spanning over 2,000 years.

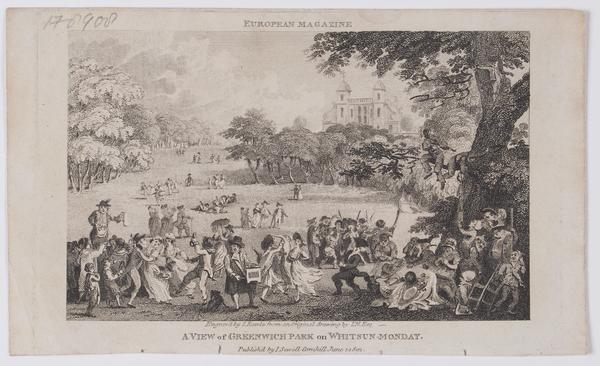

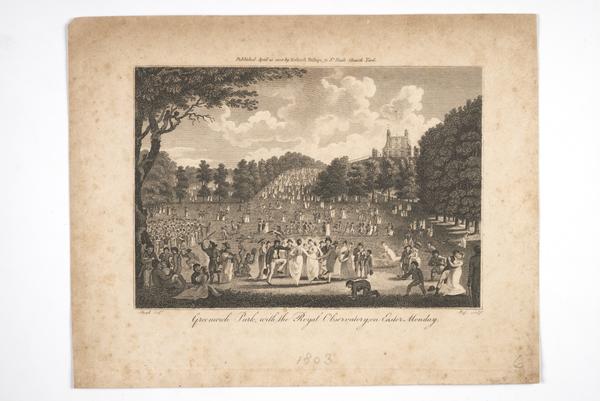

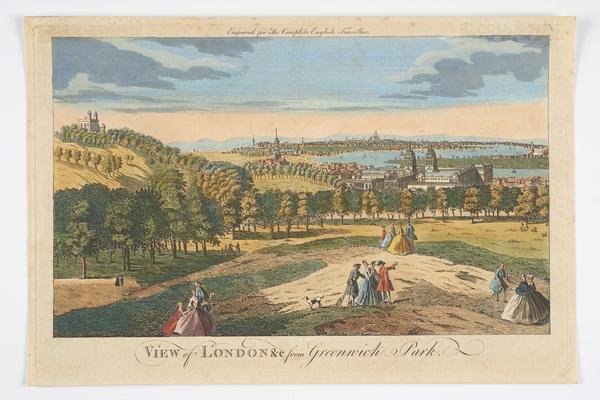

Royals, scientists, architects and everyday Londoners have all left their mark on history here. And the dramatic views have inspired artists and painters for centuries. Several 18th-century engravings in our collection show the park’s sweeping greens and London’s changing skyline.

Today, these vistas are enjoyed by those crowding into the London Marathon start line.

Standing at the centre of Greenwich Mean Time

Back in the 1800s, towns and cities based their time on the position of the sun, which meant different parts of the country had their own time systems. This made running train timetables, for example, very confusing. Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) was introduced as a way of standardising time across the country, and later around the world.

In the park’s Royal Observatory, there’s a metal strip marking the Prime Meridian. This is an imaginary line that marks a divide between measuring east and west around the globe, just like the equator divides north and south. In the 1800s, ships around the world based their shipping charts and maps on the Greenwich meridian.

From 1884 until 1972, the Prime Meridian was used as the reference point for Greenwich Mean Time, the international standard of time. When the sun crosses that line, it’s 12pm in Britain. The time in New York City in the US, for example, would be five hours behind.

GMT has since been replaced by Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), but is still our legal time in the winter.

“Four Tudor monarchs were born at Greenwich”

Greenwich’s royal transformation

The park's royal chapter began in 1433 under Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, when he first enclosed the park. However, it was Henry VII's decision in 1491 to make Greenwich his principal riverside palace that transformed the area into a centre of Tudor power.

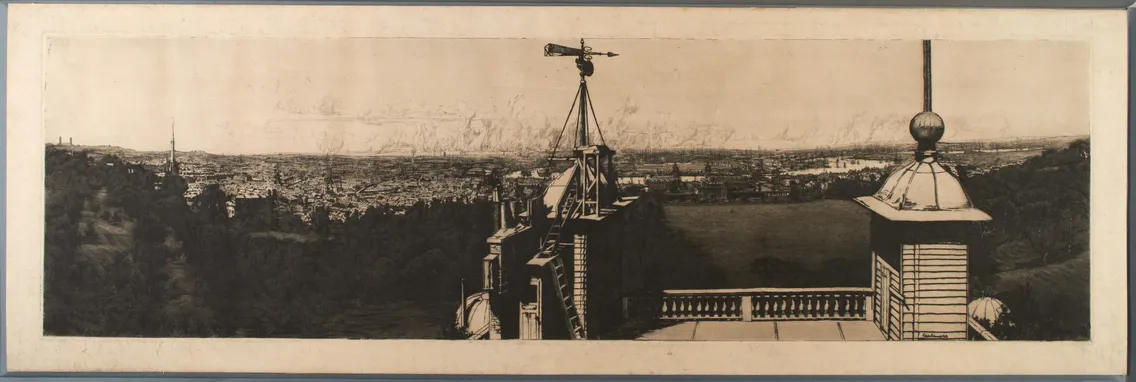

A view of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich Park from around 1740.

Four Tudor monarchs were born at Greenwich: Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I. In 1536, Henry VIII’s queen Anne Boleyn is said to have dropped a handkerchief to signal a lover, leading to a series of beheadings – including her own.

Decades later, the explorer and poet Walter Raleigh is thought to have thrown his cloak over a puddle here for Elizabeth I, saving her from getting her feet wet.

Architectural innovations

The Queen's House, a white-painted villa commissioned in 1616 by Anne of Denmark, queen of King James I, represents a revolutionary moment in British architecture.

Designed by architect Inigo Jones, it’s Britain’s first building designed according to strict rules of classical architecture, introducing Palladian architecture from Italy to England. This sparked a new era in British design which emphasised classical forms and symmetry, austere exteriors and opulent interiors.

Now, the Queen’s House holds a rare collection of artworks, including pieces by William Hogarth and JMW Turner.

Then there’s the Old Royal Naval College, a royal hospital and later a naval college built on the site of Greenwich Palace between 1696 and 1712.

The design by Christopher Wren, the architect of St Paul’s Cathedral, created a visual harmony between the park’s elevated grounds and the riverside buildings. Engravings in our collection not only show this varied perspective, but also how the park was enjoyed by Londoners.

“The Royal Observatory is the park’s crown jewel”

A place for stargazing

The Royal Observatory is the park’s crown jewel. In 1675, King Charles II commissioned Wren to design a centre of scientific advancement on the hilltop site of the ruined Greenwich Castle. Astronomers here studied the stars and the sky, and tested developments in clocks that could keep their time at sea. The Octagon Room, designed specifically for stargazing, still has its original features.

This photo shows a group of boys on a school trip to the Royal Observatory, which is part of the larger Maritime Greenwich UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Standing on the top of the hill, you get one of the best views of the London skyline.

Greenwich Park’s natural beauty

With over 3,000 trees sprawled across the grounds and 30 species of birds, Greenwich Park’s natural heritage is as rich as its scientific history. Fallow deer have even roamed freely across the park for over 450 years.

The Spanish chestnut trees, planted in the 1600s by French landscape artist and royal gardener Andre Le Notre, still line the pathways today.

Behind the Queen's House stretches one of England's longest herbaceous borders, featuring 275 metres of flowering plants.

There's also a thoughtfully designed herb garden, flower beds bursting with heritage plants, and a popular cherry blossom tree-lined avenue.