Elizabeth Garrett Anderson: A pioneering doctor

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was the first woman in Britain to qualify as a doctor. She campaigned to allow women to follow her career, and pressured the government for women’s voting rights.

Whitechapel, Blackheath & Marylebone

1836–1917

A game-changing dose of feminism

It took until 1876 for the British government to pass an act allowing women to become licensed medical professionals. Before this, there’d been pioneering healthcare workers like Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole. But only one woman had ever managed to become a qualified doctor.

This was Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. At first, medical schools and societies blocked her progress. But she kept trying, using a loophole to qualify in 1870, then setting up her own practice.

Her trailblazing inspired other women, and in 1874 she helped found the London School of Medicine for Women. Alongside her sister Millicent Fawcett, Elizabeth also campaigned for women’s right to vote.

Who was Elizabeth Garrett Anderson?

Garrett Anderson was born in Whitechapel, east London, but spent most of her childhood in Suffolk in the east of England. She was one of 11 children.

Her father was a successful grain merchant. When Elizabeth was 13, she and her older sister Louisa were sent to a boarding school for girls in Blackheath, south-east London.

In her 20s, Garrett Anderson became connected with the Langham Place group, a circle of middle-class women working to improve women’s access to jobs and education.

In 1859, she met Elizabeth Blackwell, an American woman who’d completed a medical degree in the US. With Blackwell’s aid and inspiration, Garrett Anderson became determined to become the first British woman to formally qualify as a doctor.

This postcard aimed to highlight how unrealistic the idea of ‘separate spheres’ for men and women was.

Men tried to block her ambition

In Victorian society, men completely dominated politics, education and the most respected jobs. It was commonly believed that a balanced social order relied on men and women playing different roles.

The ‘separate spheres’ theory expected men to take a public role in society. Women, on the other hand, were restricted to a domestic role as wife and mother.

Anderson’s applications to teaching hospitals and universities were all rejected. Around the same time, a woman called Sophia Jex-Blake was involved in a similar battle to study medicine in Edinburgh.

From 1860 to 1861, Anderson got a place as a nursing student at Middlesex Hospital in London. But when she attended classes for male doctors the other students turned hostile, and she was excluded.

“her achievement caused a swift backlash”

How did Anderson get her licence?

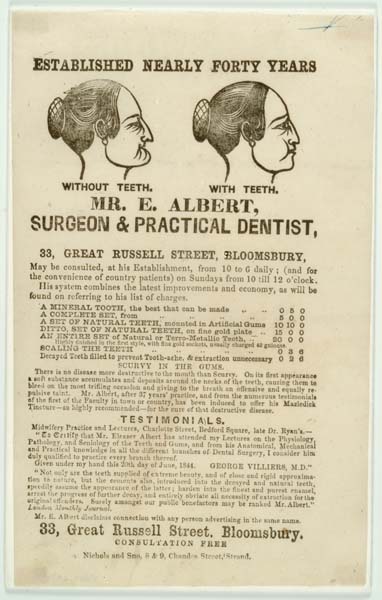

Anderson discovered that the School of Apothecaries – an old word for pharmacies – had no rules excluding women from their exams. She seized on the loophole, studying privately with licensed teachers and completing an apprenticeship with an apothecary.

Anderson passed her exams and gained her licence in 1865, becoming the first woman to have her name on the medical register, a list of licensed professionals.

However, her achievement caused a swift backlash. The Society of Apothecaries changed its rules to bar women from following her example.

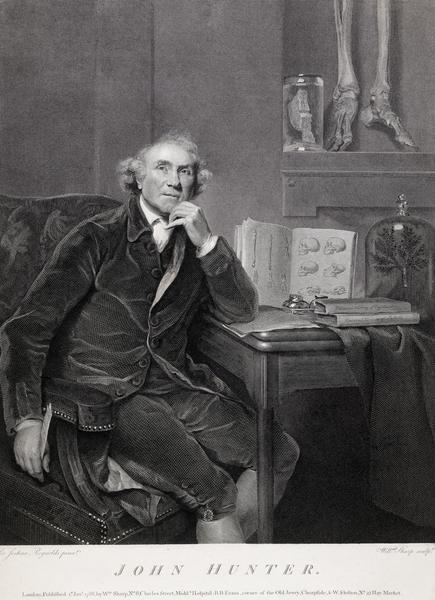

Garrett Anderson’s medical degree

Garrett Anderson’s next step was to gain a medical degree, a more respected qualification in the field of medicine. She finally found a place in a medical school in Paris and learned French to do the course.

She completed her degree in 1870, becoming a doctor of medicine (MD). The British Medical Association (BMA) allowed her to become a member. But once again, the door shut behind her. The BMA changed its rules eight years later to prevent other women from copying her.

Now qualified, Garrett Anderson opened a surgery on Upper Berkeley Street in Marylebone. Sticking to Victorian ideas of ‘decency’, the practice was limited to treating women and children.

In 1866, she set up a pharmacy for women and children in Marylebone. In 1871, she added 10 beds in the rooms above, making the New Hospital for Women. This hospital – the first in Britain staffed solely by women – was later expanded and moved to Euston Road.

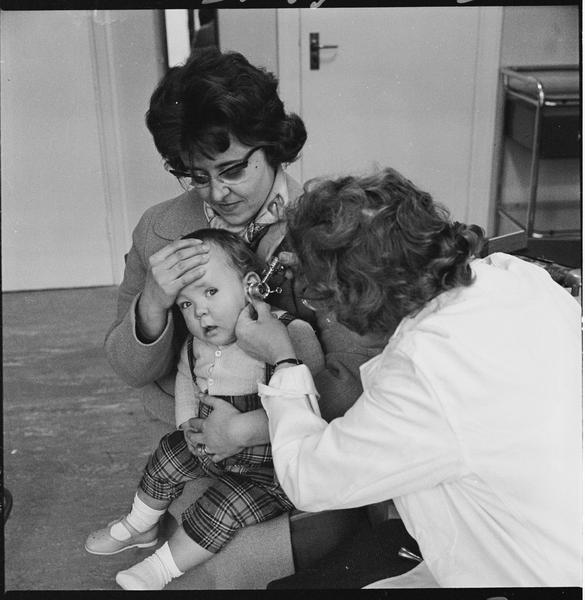

The outpatients' room in University College Hospital.

Did Elizabeth Garrett Anderson change the medical profession?

As well as forging her own pioneering career, Garrett Anderson was determined to improve other women’s chances of a medical education.

After Sophia Jex-Blake and a group of other women were barred from graduating from Edinburgh University, they decided to create their own medical school. Garrett Anderson joined them in founding the London School of Medicine for Women in 1874. She also taught classes there.

At first, the students’ qualifications weren’t recognised by the medical authorities, but the school gave women crucial experience.

In 1876, the government passed the Medical Act, allowing medical authorities to give qualified women a license.

Change came slowly. In 1911, women made up only 2% of the medical profession.

How did Elizabeth Garrett Anderson die?

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson died of natural causes in 1917, aged 81. At the time of her death, her legacy was playing out in the life of her daughter, Louisa. She was also a qualified doctor, and during the First World War (1914–1918), she ran Endell Street Medical Hospital in Covent Garden, where she cared for wounded soldiers.

To this day, her name lives on in the Elizabeth Garrett Aderson Wing of London’s University College Hospital.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson supported votes for women

Women’s campaigns for access to jobs were part of a wider struggle for greater opportunities for women during Garrett Anderson’s lifetime.

Women also demanded the right to vote in parliamentary elections, and Garrett Anderson and her family played a hugely influential role in this.

Her sister was Millicent Fawcett, who led the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) from 1890 to 1919. This group campaigned peacefully for women’s right to vote.

Garrett Anderson herself was part of an early suffragist group called the Kensington Society. In 1866, they petitioned Parliament asking for some women to have the vote.

Decades later, when Garrett Anderson was in her 60s and 70s, she became involved in the votes for women campaign.

Photos in our collection show her alongside the Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst in 1910. That day, they were at the Houses of Parliament to speak to the prime minister. He refused them. A struggle broke out between Suffragettes and the police, escalating into the violent scenes known as Black Friday.