18 August 2025 — By Matt Williams

Molly houses & queer subculture in Georgian London

In the 1700s, queer bars called ‘molly houses’ were popular spots for London’s LGBTQ+ community. These molly houses were hidden in plain sight to counter England’s harsh laws against homosexuality.

The curious case of Mr Hitchen

In 1727, Under Marshal for the City of London Charles Hitchen, was put in the pillory on Catherine Street off the Strand. He was caught having sex with a young man at the Talbot Inn, one of several ‘molly houses’ in Georgian London.

Accessing LGBTQ+ histories is often a challenge. And the primary sources of such information are, sadly, records of the criminal justice system and trials coverage that speak of homosexual activities and people.

Hitchen’s is one such case in London.

The pillory at Charing Cross, 1809.

What was a molly house?

A molly house was a public house in 1700s and 1800s England, which provided a safe space for queer people to socialise. At the time, London was not tolerant of gay men. Homosexual activities had to be acted out in the shadows, lest you wanted to be put in the pillories, or even hanged.

These challenges led to queer people forming secret and informal meeting places. They became known as ‘molly houses’.

“Molly houses were primarily a social space, away from critical eyes and the baying mob”

The case of Hitchen (sometimes spelt Hithcin) is significant because he was a member of the Society of Reformation of Manners. Founded in 1690, the group aimed to suppress similar bawdy houses and profanity. Hitchen secretly monitored and entrapped gay men in molly houses, while hypocritically engaging in same-sex relationships himself.

Facing the challenges of homophobia

Illustration from the execution broadsheet covering the execution of John Holland and William King for sodomy, in 1822. As per the 1533 Buggery Act, sex between men was punishable by death.

Sex between two men was made illegal when Henry VIII passed the Buggery Act of 1533. In the 1600s, prosecutions for sodomy increased. The punishment for being caught with a man was more severe if it could be proven that penetration occurred. You were also more likely to be prosecuted if you didn’t have the money and status to pay off the law enforcers or flee abroad.

In this homophobic atmosphere, molly houses presented a safe space for gay men in Georgian London. While there was a sexual element to some molly houses, they were primarily a social space, away from critical eyes and the baying mob.

Why was it called a molly house?

‘A Morning Frolic, or the Transmutation of the Sexes’ is an 18th-century satirical print, often attributed to John Collet. It depicts a scene of revelry and gender-bending, likely intended as social commentary.

The origins of the term ‘molly’ to mean homosexual men are debated. One theory is that it’s derived from ‘Mary’ or ‘mulier’, the Latin word for women, referring to effeminate men.

Molly houses flourished in the 1720s and 1730s, and usually took the form of a back-room or first floor of a pub, coffee house or chocolate house. These places would be almost exclusively frequented by the working class, such as tradesmen, drapers and butchers. There would be socialising, drinking and dancing, particularly on Sunday evenings.

Gender nonconformity in molly houses

Masquerade parties on Christmas and New Year’s Eve were common. Crowds could range from 10 to 40 attendees. They would often assume fake names, mostly female ones, such as Plump Nelly and Mary Magdelin.

Attendees would dress up as women and adopt personas to match their assumed names. Molly houses were not only a place for homosexual men but also gender non-conforming people.

“There were more molly houses in London in the 1720s than gay clubs in the 1950s”

Miss Muff, also known as Jonathan Muff, was known to regularly organise drag parties at their establishment in Black Lion Yard in Whitechapel. This was also the location of a major raid in 1728.

The ‘Old Beau’ in this 1773 satirical print is a ‘macaroni’, a social stereotype of the 1770s. Macaronis were mercilessly mocked for their supposed effeminacy with the suggestion of ‘sodomy’.

Organised queer subculture in Georgian London

Some molly houses had backrooms called the ‘chapel’, with a large bed. So called as it was sometimes used for fake ‘weddings’ between molly house attendees.

Interestingly, there were more molly houses in London in the 1720s than gay clubs in the 1950s. Records show there were around 20 molly houses under investigation by the Society of Reformation of Manners (SRM) in the mid- to late 1720s.

Some popular places at the time included areas around Moorfields, London Bridge and the Talbot Inn on the Strand. A popular molly house stood on Tottenham Court Road and another on Bird Cage Alley, alongside St James’s Park.

One very popular molly house was owned by Margaret Clap, aka Mother Clap.

“The 1730s saw a decline in molly houses in London”

Mother Clap’s molly house

By the early 1700s, the SRM was aggressively raiding molly houses. The most notorious was the raid on Mother Clap’s molly house in 1726.

It was established in Holborn by Margaret Clap, who hosted up to 40 people every evening in her coffee house. Mother Clap was highly regarded among the queer community and is even known to have given false testimonies in aid of gay men arrested on sodomy charges.

The raid resulted in multiple arrests, hangings at Tyburn and Marget Clap herself was put in a pillory and imprisoned for two years. But many couldn’t be convicted due to the lack of physical evidence.

The 1730s saw a decline in molly houses in London, possibly due to increased raids or the rise of brothels and cruising. Areas like St James’s Park and the Royal Exchange became popular cruising grounds.

There is, however, evidence from other raids that molly houses persisted into the 1800s.

Cruising in public bogs

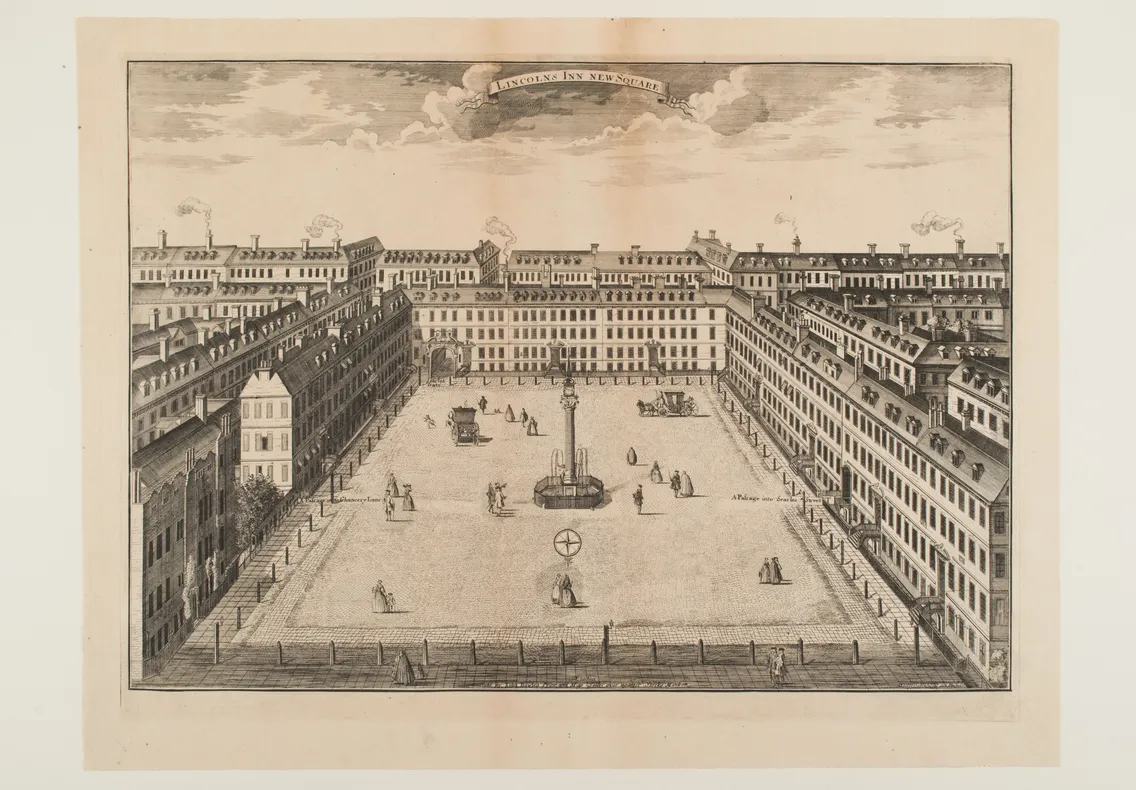

Public toilets started appearing in London from the late 1600s onwards, and men began cruising in them almost immediately. One of the earliest and most popular was Lincoln’s Inn bog house.

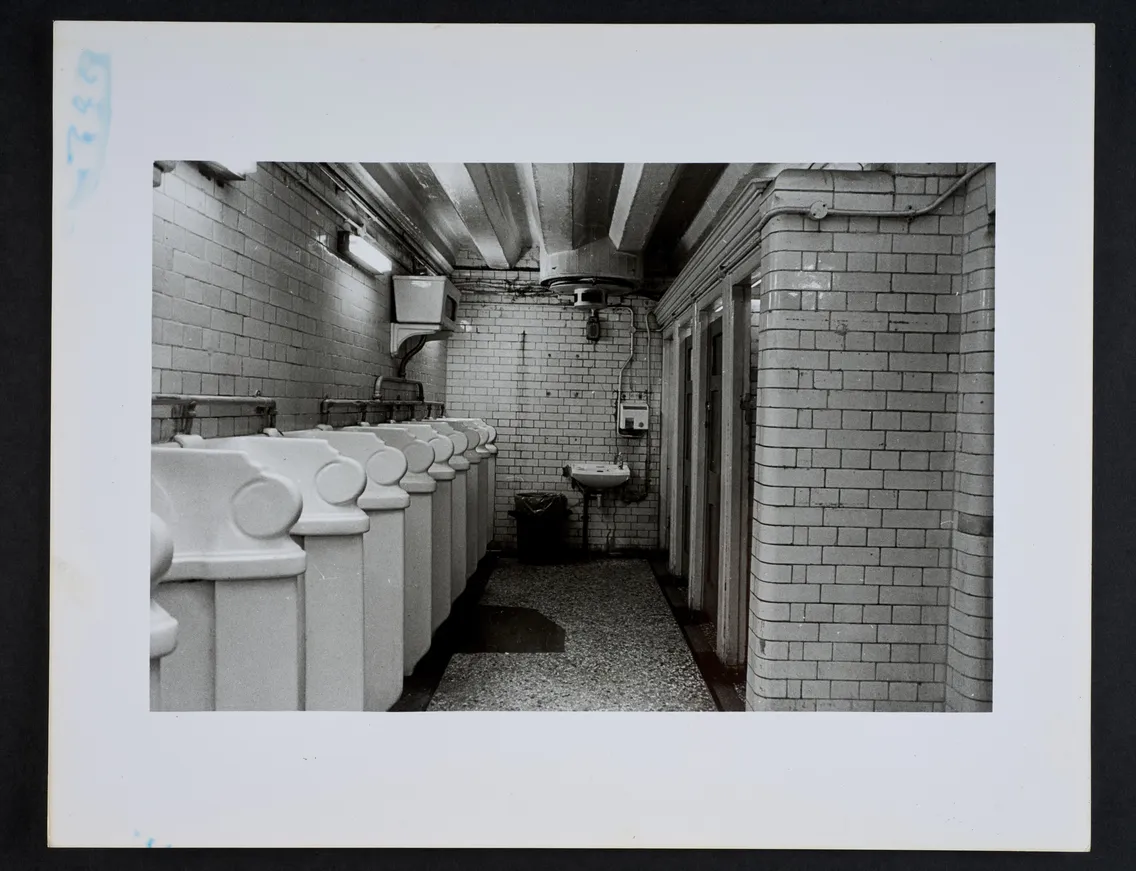

The culture of the public toilet being the scene of gay cruising continued for centuries. A 1937 publication, For Your Convenience: A Classic 1930’s Guide to London Loos, is regarded as the first gay guide to the city of London. The book mapped out many of the cruising locations before homosexual acts were decriminalised in England in 1967.

Another interesting collection of photos in London Museum features London public toilets by Phil Polglaze. In the 1980s and 1990s, Polglaze was employed to photograph public toilets that were often used to help the legal defence of men arrested in ‘cottaging’ cases.

While molly houses were such an integral part of Georgian London, not many of these buildings have survived. We owe what we know about this period of Georgian London to the historian Rictor Norton, who examined newspapers and court records and pieced together the story of Molly Houses. Some documentaries and portrayals in TV series and plays do give some idea of their popularity and significance.

For researchers, though, court records primarily offer a glimpse of how men in Georgian London created a third space for themselves during a hostile time for queer people.

Matt Williams is Project Assistant (Collections) at London Museum.