The toilet photos that saved gay men on trial

From 1979 to 1996, Phil Polglaze photographed London’s public toilets to aid the legal defence of men arrested in ‘cottaging’ cases, recording a time when homosexuality was persecuted.

1980s & 1990s

A public toilet in Balham.

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

‘Bog jobs’ and gay encounters

"This is a piece of history you can’t deny,” says Phil Polglaze. He spent years documenting London’s public toilets, the places in parks, department stores and train stations where gay men were arrested for buying, selling and having sex.

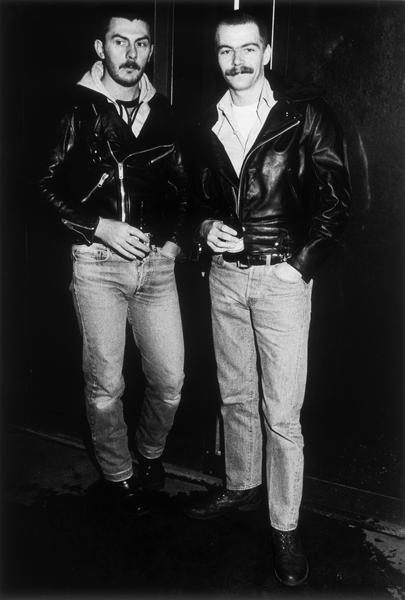

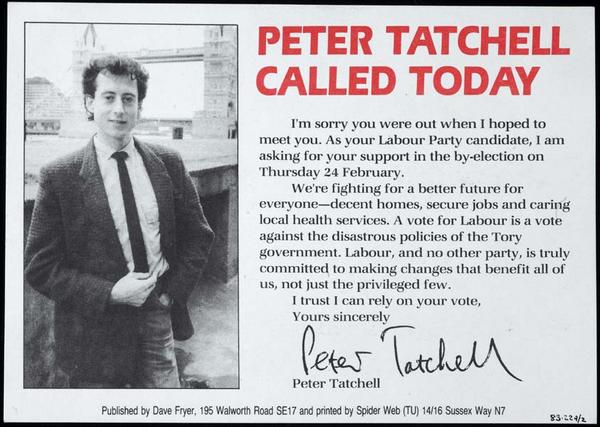

Homosexuality was partly decriminalised by the Sexual Offences Act of 1967. But in the 1980s and 1990s, remaining anti-gay laws and the AIDS crisis meant that many gay men stayed closeted, keeping their sexuality private.

That made secretive sex, often in public places, a necessary way to meet others in fleeting, exciting encounters.

It was risky. If caught, gay men risked a charge of gross indecency or ‘buggery’, punishable by imprisonment. In the decades after 1967, as many as 15,000 gay men are estimated to have been convicted of these charges.

What is cottaging?

The term ‘cottaging’ refers to cruising in search of sex, or having casual sex in public toilets. Most often – but not exclusively – it’s associated with gay men.

The word comes from the 19th-century use of ‘cottage’ to describe small public toilet blocks in Britain (also dubbed ‘tea-rooms’), which were popular places for a quick thrill.

Why did Polglaze take these photos?

In 1974, Polglaze was working as a geography teacher at a south London school. Already a keen amateur photographer, he used the school’s darkroom to teach himself how to print pictures. The London borough of Southwark then employed him as a photographer through the 1980s and 1990s.

In 1979, Polglaze was approached by a lawyer friend who needed an unusual set of pictures taken.

The lawyer was working on a cottaging case. The argument in defence of his client depended on demonstrating a certain sightline in a north London public toilet.

Unable to bring the judge and jury to the location, he needed to rely on photographic evidence. Polglaze was asked to do the job. So began a 20-year occupation during which he visited and photographed the scene of alleged crimes, including robbery, arson, murder, rape and road accidents. He always worked on behalf of the defendant.

Questioning the police record

As a straight geography teacher with a love for motorbikes, Polglaze was an unlikely advocate for the cause. But that first commission brought in good money: “With all those prints at the end of the first case, I ended up with £280, which back in 1979 was quite a decent fee.” So he continued.

Typically, it was the police who took photos of a crime scene, and those pictures were used in the investigation.

Polglaze would be brought on much later in the case. Often he would be given both the prosecution and defence statements to work with, in the hope of creating visual evidence which might clear the client.

"I had a much greater understanding of the crime compared to the bloke who photographed the blood on the wall,” he says. “I could work out through years of experience and mathematics and physics and stuff what [camera] they were using, and I was thinking: is that the truth?”

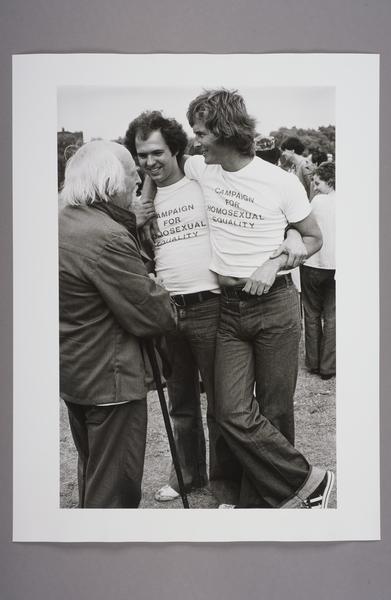

A defendant demonstrating where he was stood when arrested for cottaging.

“these stories were printed in the local newspapers. I was honest, as much as I could be, for these poor blokes”

Phil Polglaze

‘Bog jobs’

Between 1979 and 1996, Polglaze applied himself – “with common sense and honesty, of course” – to the task of interpreting the language of legal documents and turning that into imagery that would support the defendant.

The ‘bog jobs’, as he calls his photographs of the toilets, were among the less gruesome assignments he received, although much was at stake for the men accused. “For some people it ruined their lives. Some were guilty, yes; some were innocent, yes. But don’t forget these stories were printed in the local newspapers. I was honest, as much as I could be, for these poor blokes.”

Over the years, Polglaze documented more than 50 public toilets across London, from Battersea to Blackheath and Kingston to Greenwich.

Police operations

Polglaze realised how easy police were finding it to arrest and prosecute gay men. They often employed “pretty police” in plain clothes to set up gay men, or used dubious surveillance tactics.

Polglaze remembers a toilet near Wembley, where in 1984, police entrapped and arrested 400 men over a month by hiding in the roof and drilling holes in the ceiling to observe the toilets below. Polglaze’s pictures show where the police climbed up and the rubbish they left behind.

“Men would turn up, the coppers would nick ’em, they would plead either guilty to get it done and dusted, or they would plead not guilty. If you pleaded not guilty, you are rolling the dice… But there were some fantastic firms of solicitors who really worked over and above for their clients,” he explains.

Rubbish left behind by police at a toilet near Wembley.

Lines of sight

In the early 1980s, Polglaze was doing four or five bog jobs a week. It’s an indication of how much police activity was directed towards catching gay men and a reflection of the political climate.

His purpose was always to prove what could or could not have been seen by the police or a witness from a certain angle. It was all about the lines of sight.

In a September 2005 interview with the Gay Times, he said: “My job as a photographer was to assess the structure of the place and establish sightlines. It was a way of establishing facts without taking juries to the location, which would’ve been unthinkable. You have to be neutral, you can’t bend the truth in order to get someone off. But you can establish sightlines: could a policeman genuinely have seen an erect penis from such-and-such an angle? Could sex really have taken place through this glory hole, or under this cubicle partition?”

Sometimes the photographs helped the defendant. At other times, visual evidence of the toilets was more likely to work against them. Sexually explicit graffiti, for example, was a recurring challenge, acting as evidence that sex was happening there.

“It is easier to put things into pictures than to take them out,” he says. “For instance, there were some toilets with ‘meet me big boy tonight’ or ‘here’s my phone number I’ll show you a good time’ [scribbled on the wall]… If you include that in a photograph, would you be influencing a jury? So you just bring the angle down a bit. Your brain fills in the rest but you don’t see it.”

The case of the Norwegian sailor

Polglaze remembers one case in Kingston in 1990. A Norwegian seaman had been charged over a sexual encounter which was said to have involved him reaching his arm under the partition between two cubicles.

Polglaze went along to the toilet with the barrister, the solicitor and the solicitor’s clerk, where they restaged the suspected event.

In the resulting photographs, the clerk can be seen lying on the floor, sticking his arm under the wall. The point was to demonstrate that the sailor could never have reached far enough to achieve what he was accused of.

But once in the courtroom, the barrister told his client not to move, just to sit very still. He was found not guilty, Polglaze chuckles, but “the humour is that when the defendant left the box, he had the longest arms you have ever seen in your life!”

The lost history of public toilets

Polglaze's bog jobs came to an end when Legal Aid was cut for cottaging cases. The struggle for gay rights also gained ground in the 1990s, changing the culture and lessening the need to have sex in secret.

Many of the public toilets photographed by Polglaze have since disappeared: knocked down, boarded up, or even converted into flats or cafes. Some of them were architecturally interesting spaces with beautiful ceramic urinals and hand basins, ironwork or decorative fittings.

In our collection, we have two urinals from the former Holborn Underground Public Conveniences, which closed in 1980.

Our collection also includes the 1937 guide to public toilets in London by Thomas Burke, For Your Convenience – a thinly veiled guide to cottaging spots around the capital.

We also have 92 prints and contact sheets by Phil Polglaze. These continue to tell the story of public toilets and illicit encounters between gay men, a social history that has largely remained hidden from sight.