09 January 2026 — By Kate Sumnall

The most infamous scandal in Victorian London?

Colloquially known as the Shadwell shams because of the place they were ‘mudlarked’, the Billy and Charley forgeries from the 1800s are considered one of major Victorian forgery cases in the UK.

The story of the Shadwell Shams and the mudlarks turned counterfeiters is one of intrigue, deceit and ingenuity. It all started around 1844, William (Billy) Smith was a mudlark, about 10 years old. He searched the Thames foreshore during low tides for things that could be sold, such as scrap metal and rope, but also historical artefacts.

There were dealers who would pay good money for newly discovered artefacts and then sell them on to collectors. Demand was high.

“In 1857, Billy and Charley sold 1,100 objects for around £200, that’s worth about £19,000 today”

In 1857 Billy Smith, now an adult, was working with Charles (Charley) Eaton. They decided to remove the luck and unpredictability of finding artefacts on the foreshore and they began to make their own ‘historic relics’.

Inspired by objects they had seen, Billy and Charley carved moulds and melted lead to cast medallions like this one below. To make it look real, they used acid to ‘age’ the metal and painted on Thames mud.

Then they claimed they were new discoveries found during the works at Shadwell Docks.

A fake Victorian pilgrim badge.

A successful forgery business

It was reported that in 1857, Billy and Charley sold 1,100 objects for around £200, that’s worth about £19,000 today. They made a large range of different objects in lead and even bronze, most resembled medieval artefacts. Some seem to be inspired by Roman or Greek antiquities.

Some of the objects they made are unlike other objects from London’s history, such as this open-work fish with a figure of a man inside. Perhaps, representing Jonah in the whale from the Bible.

A fish-shaped forgery with a figurine of a saint inside it.

Fake or real? Battle of the experts

There was debate within the archaeological world over whether they were real or, as some suspected, fake.

On one side was Charles Roach Smith, co-founder of the British Archaeological Association. He felt there were enough similarities between Billy and Charley’s ‘finds’ and the newly discovered Medieval pilgrim badges like the ones in our collection from the Thames. At this time there were so many new discoveries from the Thames as a result of all the building work and the mudlarks. Many were new types of artefacts that had come from all over medieval Europe. When faced with so many new types of objects that were authentic, it was the perfect time and place for Billy and Charley to slip in their fakes.

A late 17th-century ink map showing a prospect of London from London Bridge to Shadwell Dock to the right.

Arguing against their authenticity was Henry Syer Cuming, Honorary Secretary of the British Archaeological Association. He was suspicious about the inconsistencies on the objects such as unintelligible inscriptions. Billy and Charley were illiterate and they copied the shape of letters but without understanding the original writing. They also wrote dates on the objects in Arabic numerals which were not common in medieval Europe.

Cuming spoke to labourers at Shadwell docks, the supposed findspot. They neither knew the objects nor Billy and Charley. Cuming even bribed a tosher (someone who searched the sewers for valuable items), who broke into Billy and Charley’s workshop, and brought back moulds and objects as undeniable evidence.

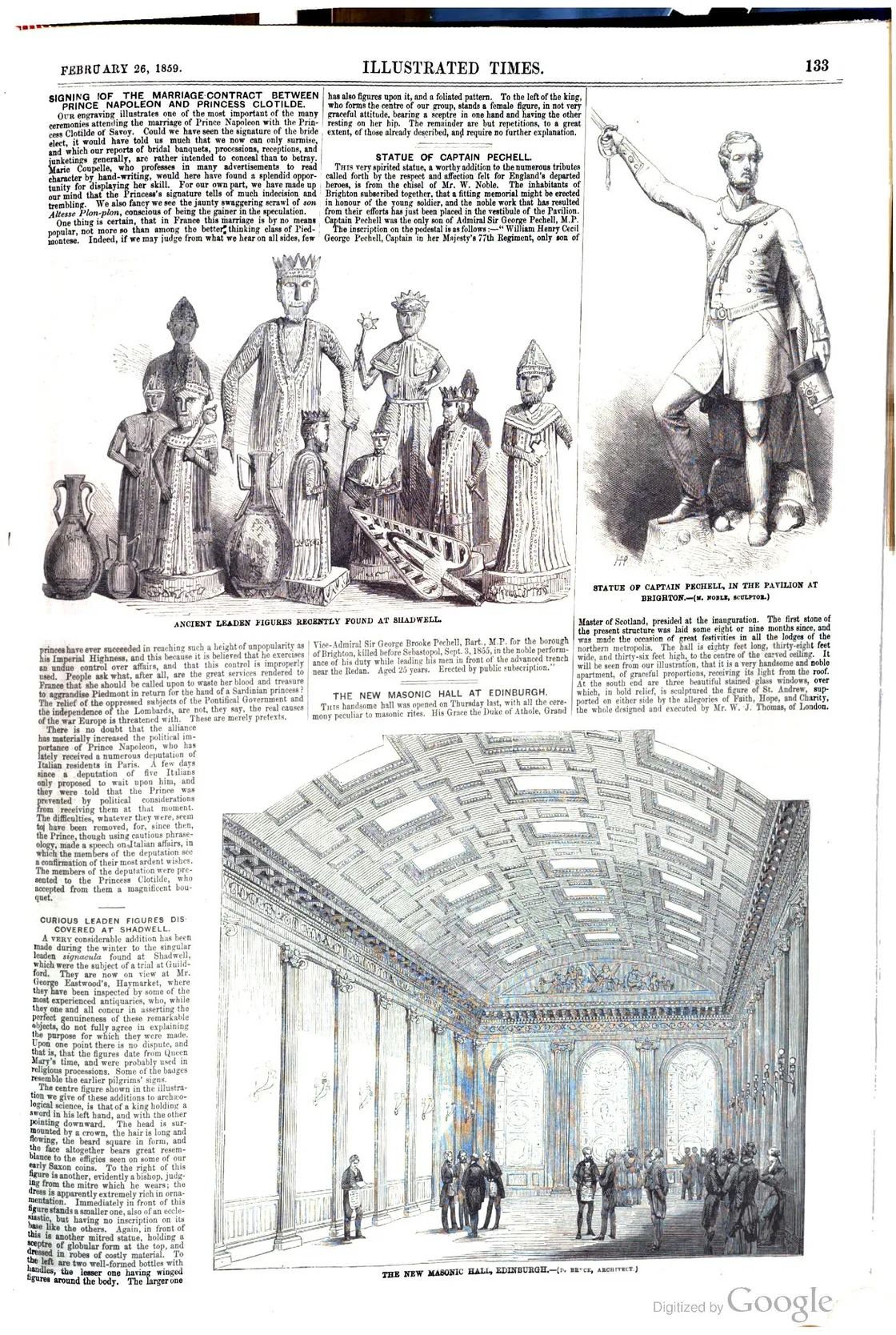

None of this deterred Billy and Charley or William Edwards, a London antique dealer who was their main dealer. Edwards referenced the arguments in an advert for “newly discovered historic relics” that he placed in the Illustrated Times on 26 February 1859. There were still plenty of buyers.

The Billy and Charley forgeries covered in the 1859 edition of the Illustrated Times.

What happened to Billy and Charley?

As word spread about the deception, Billy and Charley had to travel further away, claiming their fakes were found while working as labourers in Guildford and Portsmouth. However, they didn’t escape notice and they were brought before court a number to times. In 1867, the court in Aylesbury ruled that it was unclear if Billy and Charley knowingly sold forgeries. They were released.

By 1869, the ‘Shadwell shams’ were so notorious that demand lessened. Cuming bought seven for just a penny to use to warn others of the deception.

Charley Eaton died in 1870 of consumption, as tuberculosis was known then, near Shadwell docks, where it all began. There are no further accounts of Billy Smith, it seems he died without record.

One of the Billy and Charley forgeries.

The story of the Shadwell shams has captured public imagination over the years and the pieces that Billy and Charley made continue to be popular. Some are in major museums, alongside the artefacts that they mimicked. London Museum has the largest collection, we look after more than 200. The Cuming Museum has the only known mould as well as the pieces that Henry Syer Cuming acquired to teach about the forgery.

Historian Robert Halliday first heard about Billy and Charley from his mother and since then years of careful research has created the most complete account of their deception. According to his research, the duo produced thousands of forgeries and fooled many for more than a decade. Billy and Charley have earnt their place in history books.

Kate Sumnall is Curator, Archaeology at London Museum and Lead Curator of Secrets of the Thames.

Please note that you must have a permit from the PLA to go mudlarking on the Thames foreshore.