What was the Winter of Discontent, 1978–1979?

During the freezing winter of 1978 to 1979, workers across the country went on strike to protest stagnated wages. The walk-outs impacted many parts of day-to-day life, including healthcare, transport, waste collection and road haulage.

1978–1979

When morale dipped as low as the thermometer

There are two things the winter of 1978 to 1979 is remembered for: bitterly cold temperatures, and bitter disputes between trade unions and employers.

Trade unions were angry at the Labour government’s 5% limit on pay rises. They organised walkouts in London and across the country, in both the private and public sector, affecting schools, transport, healthcare and waste collection.

It was a transformative moment in 20th-century Britain. The industrial action was later dubbed the ‘Winter of Discontent’, borrowing words from the opening line of William Shakespeare’s play Richard III.

Press coverage and public perception of the strikes combined to create a myth that Britain was under the thumb of trade unions who aimed to grind the country to a halt. This narrative has persisted for decades. And the memory of this cold, tense winter is frequently brought back into the conversation during industrial disputes today.

The Labour government’s inflation issue

The 1970s saw periods of high inflation, which is when the prices on goods and services rise. Inflation peaked in 1975 at around 25% – the highest figure since the First World War (1914–1918).

To try and bring inflation down, the Labour prime minister James Callaghan imposed a guideline to cap pay rises at 5%. This rested on the idea that companies have to increase their prices if they’re paying higher wages, which fuels inflation further.

The 5% limit wasn’t compulsory. But Labour threatened to sanction any government contractor who broke it.

Inflation was around 8% in 1978. So a capped 5% increase on wages would mean workers would still get less for their money. Essentially, it would be a pay cut.

The Ford Motor Company strike

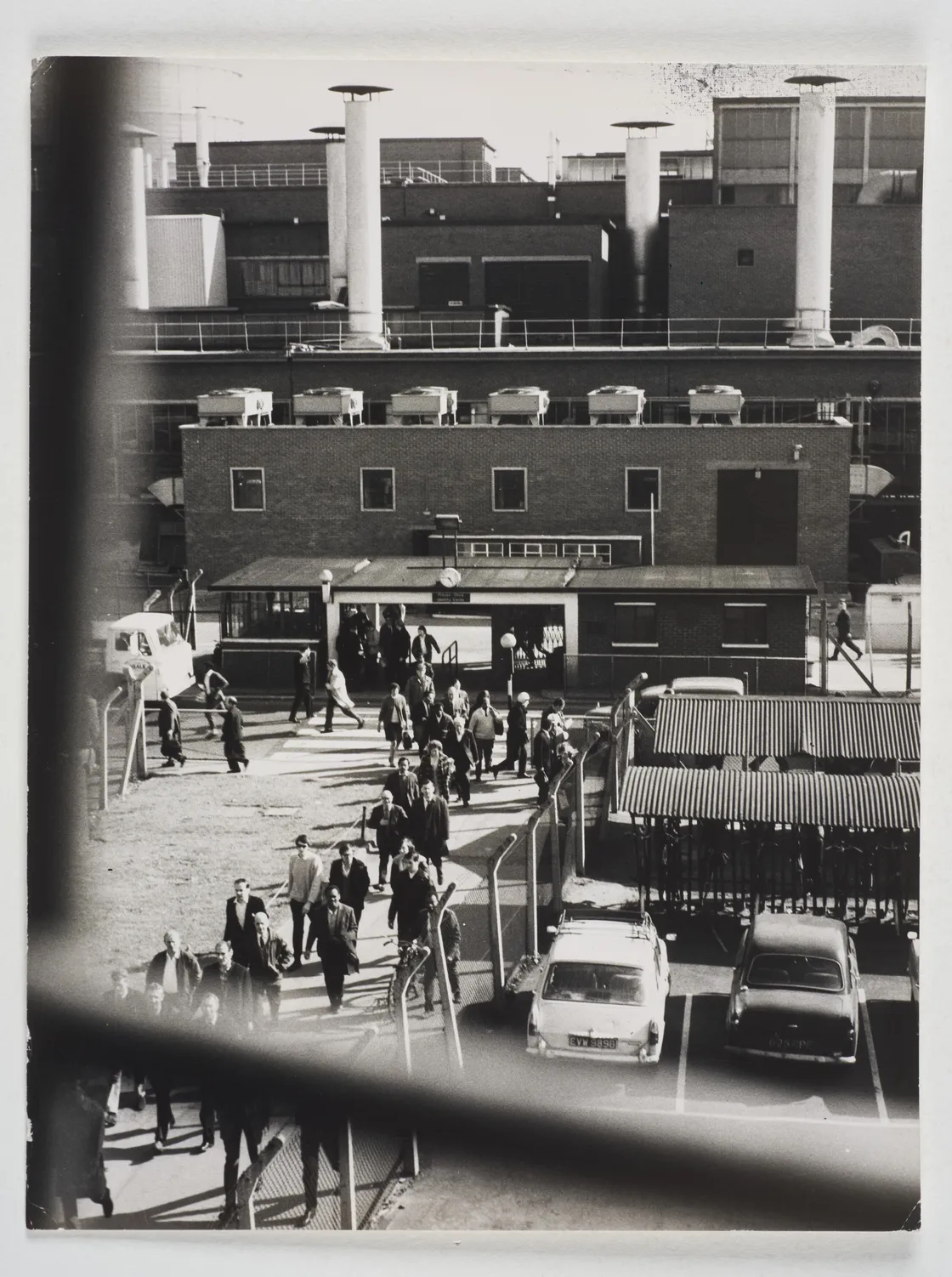

On 22 September 1978, workers at the Ford Motor Company plant near Liverpool went on strike. The unions wanted to secure a pay rise that went higher than the government’s 5% policy, and a 35-hour working week.

The following day, workers at other Ford plants, including the main one in Dagenham, east London, walked out. The Times newspaper reported from the Dagenham plant when workers voted to strike, running with the headline: “It took 16 minutes to bring Ford plant to a standstill”. By 26 September, 57,000 Ford workers had gone on strike across the country.

Photograph of the Ford factory in Dagenham.

In November, with the strikes costing Ford money and affecting production, the company decided to accept a 17% pay rise.

The Ford strike opened the floodgates for many more workers fighting for wage increases in the following months. In December, the House of Commons voted to prevent the government imposing sanctions on government contractors like Ford who gave pay rises above the 5% limits. The pressure mounted on the Labour government.

“Crisis? What Crisis?”

On 10 January 1979, Callaghan returned from a summit in Guadeloupe and was met by reporters at London’s Heathrow Airport. He said: “I promise if you look at it from the outside, I don't think other people in the world would share the view that there is mounting chaos".

James Callaghan told reporters there was no “mounting chaos” in Britain at Heathrow Airport, 10 January 1979.

The tabloid paper The Sun ran with the front-page headline “Crisis, What Crisis?”, framing the prime minister as starkly out-of-touch. Callaghan never actually said this, but the words followed him for the rest of his political career.

So what was the ‘crisis’? Railway workers, haulage drivers and petrol drivers had all taken action that January. This had a widespread impact on British society, including disrupting the supply of food and petrol.

The chaos caused by the snow and extremely cold weather only made things worse. That January, the average temperature was close to 0C.

The right-wing press whipped up fear of the severe impact of the strikes, and attacked the strikers themselves as greedy and self-serving. This was “Britain under Siege”, according to a front page of the Economist magazine. Strikers were depicted as holding the country to ransom.

The strikes intensified after the ‘day of action’

On 22 January 1979, against the backdrop of the bitter cold weather, public sector unions held a ‘day of action’. It’s thought 1,250,000 workers took part in the 24-hour strike.

The general secretary of the General and Municipal Workers Union said that those taking part “literally care for us from the cradle to the grave". These included NHS workers, airport staff, school workers and waste collectors, many of them people already working on low wages.

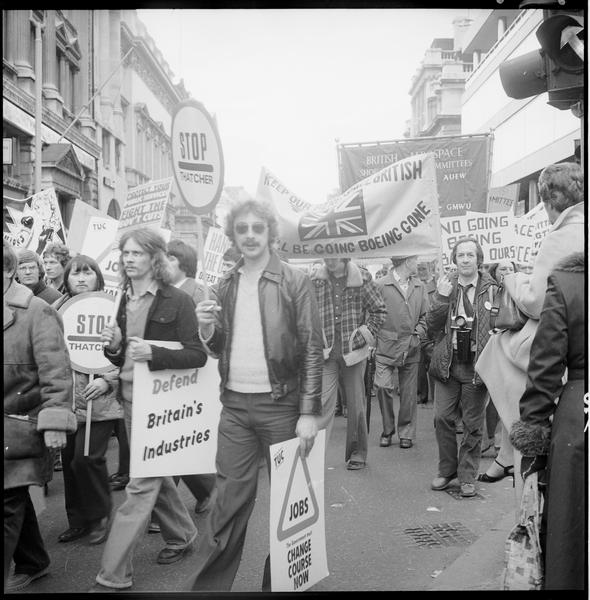

There were also mass demonstrations in London, Cardiff, Edinburgh and Belfast to demand a £60-a-week minimum wage. Tens of thousands of people marched through the English capital.

Many workers stayed on strike in the following weeks. Images of rubbish piled up on the streets have endured in the public memory.

Local councils ran out of space and were forced to use parks and squares as emergency refuse sites. Poison had to be used to control rodents. Images of sacks piled high in Leicester Square were published across the country. It was dubbed ‘Fester Square’ in the media.

The impact of the Winter of Discontent strikes

The industrial action led to negotiations between the Trades Union Congress, who represent most unions, and the government. On 14 February – Valentine’s Day – they published a joint statement that marked the beginning of the end of the winter-long disputes.

Some strikes continued in the weeks after, but most workers had returned to work by the end of February. Many unions won pay rises from employers that went above the 5% limit. Waste collectors, for example, accepted an 11% increase in pay and an extra £1 a week (around £5 today).

The Winter of Discontent was one of the main factors that brought down the Labour government in the May 1979 general election. Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher was elected prime minister and introduced significant restrictions on the power of Trade Unions.