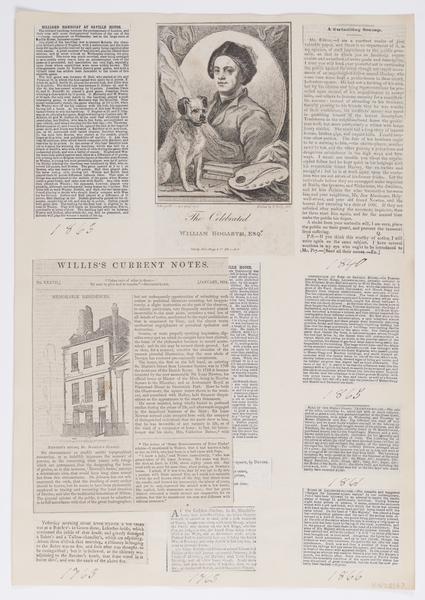

William Hogarth painted London behaving badly

William Hogarth is one of the most celebrated English artists of the 18th century. A Londoner all his life, he won fame painting and engraving satirical scenes of the city with a moral message, cramming unruly Londoners into every inch to make his point.

1697–1764

Hogarth was a Londoner

William Hogarth was born in Bartholomew Close, near Smithfield Market, on 10 November 1697. He went on to live in Leicester Square – then called Leicester Fields – until his death in 1764. His success also allowed him to buy a country home in Chiswick, west London, which is now a museum.

Printing money

Hogarth started as an apprentice silverworker. But by 1720, when he was in his early 20s, he’d set up his own engraving shop, where he printed business cards and small illustrations. The image shown here is a funeral invitation. Hogarth studied drawing at local schools, made art-world connections, and was painting by the late 1720s.

A Harlot’s Progress, 1732

By his 30s, Hogarth had established himself as a painter of group portraits. But his fame came when he began painting and engraving stories across a series of scenes. The stories exposed problems in modern society, mixing serious issues with humour. It proved a popular combination. His first was A Harlot’s Progress, which followed a woman forced into the sex trade after arriving in London.

Southwark Fair, 1733

Hogarth was a smart businessman who reproduced his paintings as engravings to reach a wider audience. Without the need for rich patrons to back him, he was free to choose his subjects. London is his most frequent setting, and Hogarth brought the city to life with a cast of rowdy, ridiculous and grotesque characters – both rich and poor.

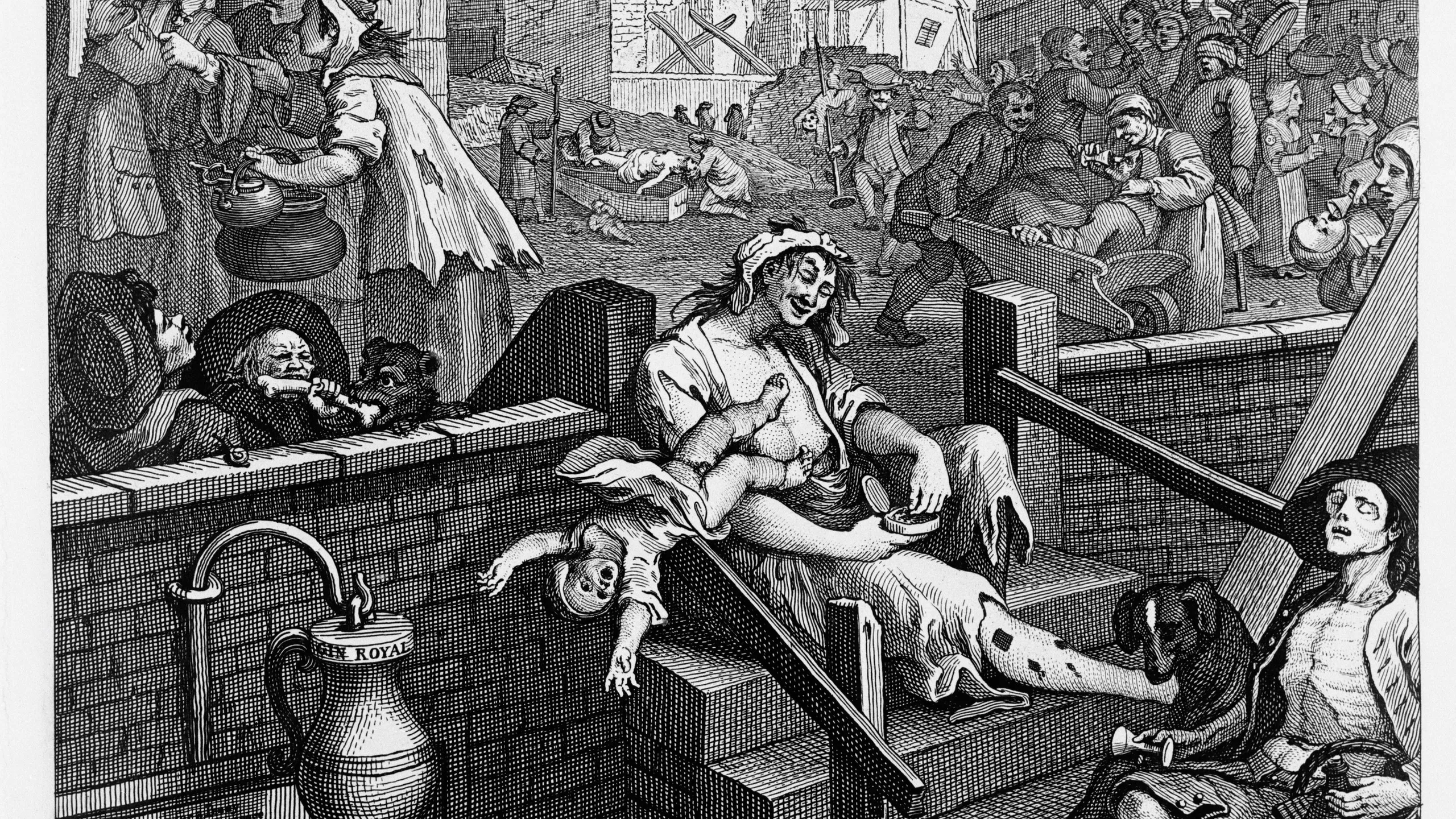

Gin Lane, 1751

This vivid picture of neglect, disorder and wickedness dramatises the effects of gin on the poor area of St Giles, where alcohol addiction was a major problem. Gin was extremely cheap in the 1700s and was linked to a rise in crime, poverty and the death rate. Hogarth’s print was made as propaganda for a campaign to tax spirits. It was published alongside Beer Street, an image showing an idealised community of beer-drinkers.

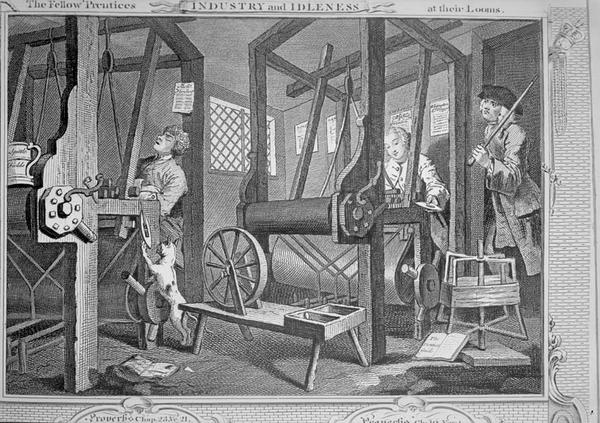

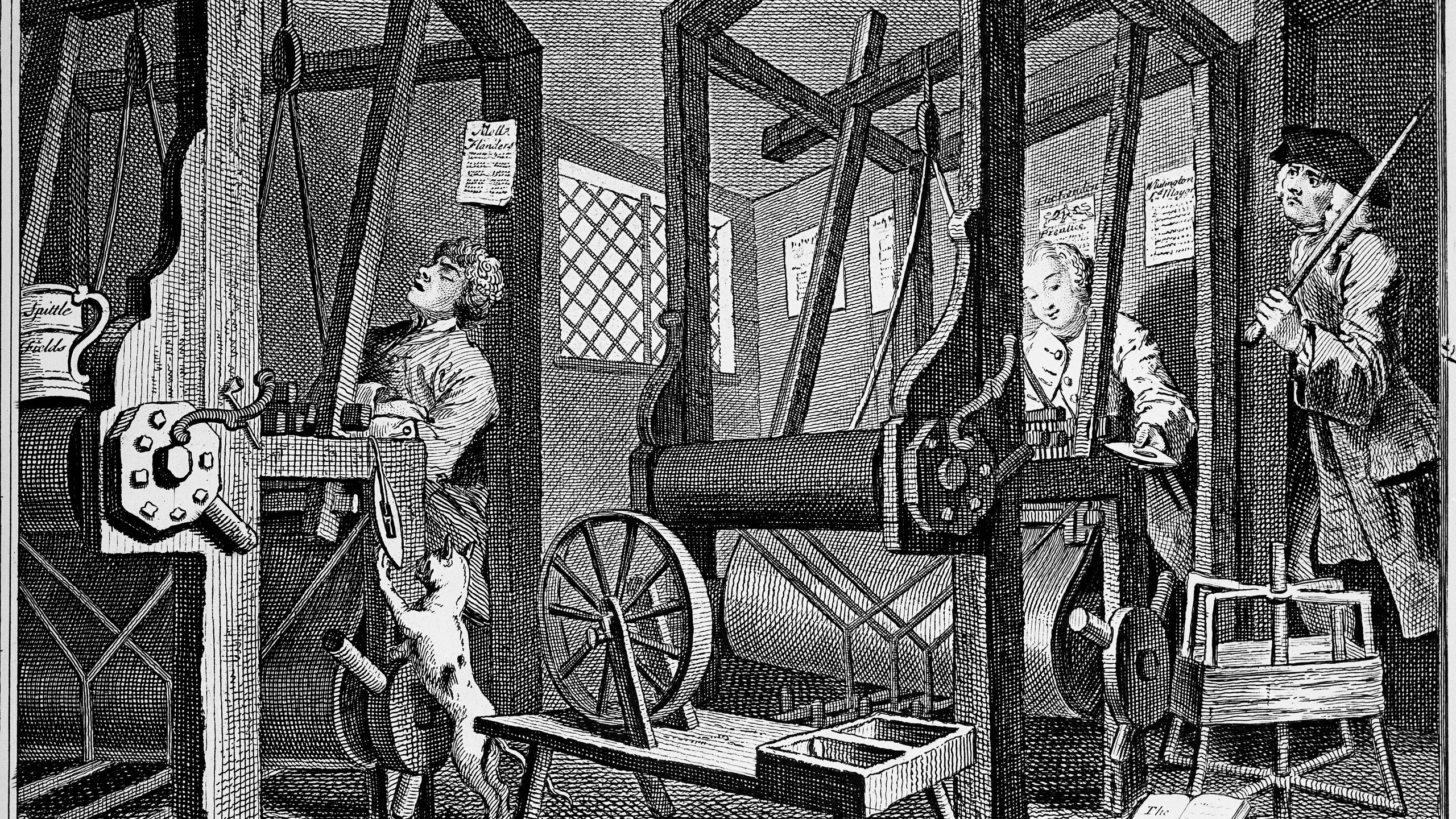

Industry and Idleness, 1747

Hogarth’s Industry and Idleness series told the stories of two apprentices with contrasting attitudes to work. It’s a great example of his art’s moral purpose. In the first scene, both apprentices are shown in a silk-weaving workshop belonging to Huguenots, Protestant refugees from France. By the end of the series, the apprentice shown sleeping is publicly executed. Meanwhile, the one shown hard at work ends up as the lord mayor of London.

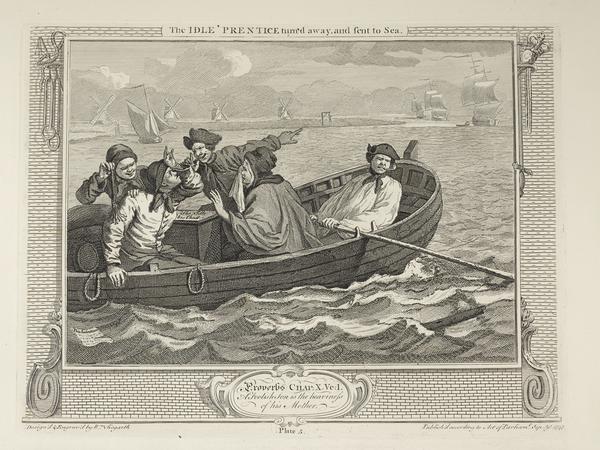

Sent to sea

Tom Idle, the lazy apprentice, becomes so poor that he’s forced to work at sea. In this scene, he’s being rowed out on the River Thames. The land in the background is probably Millwall, on the Isle of Dogs. A gibbet – where the bodies of executed sailors were displayed – is also visible.

Execution at Tyburn

Here we see the “Idle ‘Prentice” executed at Tyburn, then London’s main site for public executions. In the previous engravings, Tom Idle progressed from gambling to robbing and murdering. Hogarth intended this series of engravings to be a lesson on the importance of work “for the use and instruction of youth”.

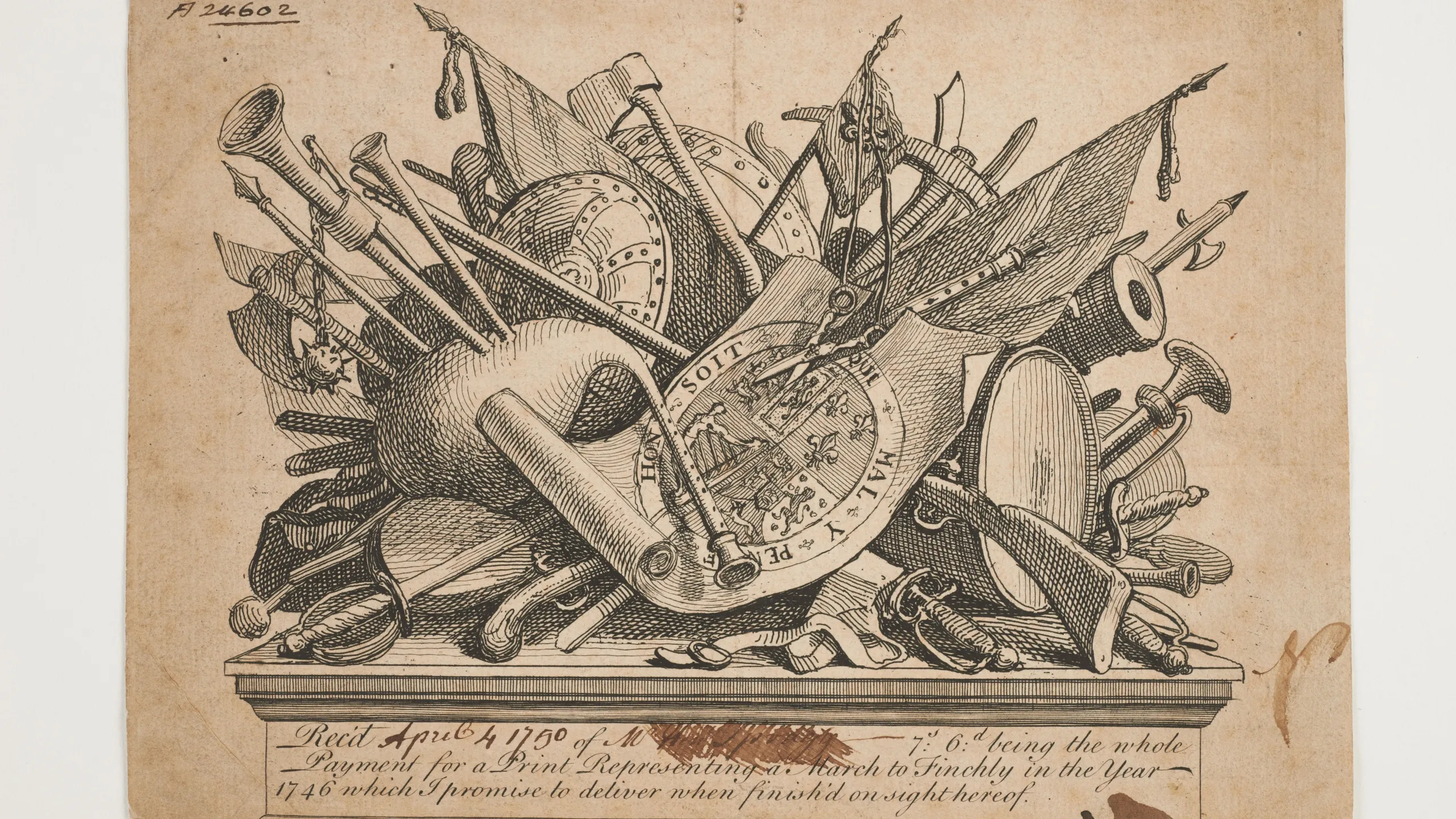

Subscription and copyright

Hogarth sold his series of engravings by subscription. Customers ordered and payed for copies in advance. The receipt shown here lists the cost, title of the piece and the promise “to deliver [it] when finish'd”. Hogarth lobbied for the Engravers’ Copyright Act of 1735, the first law of its kind, to prevent his work from being copied. He wisely waited for the law to pass before publishing engravings of The Rake’s Progress.

March to Finchley, 1750–1751

And this is the engraving Hogarth promised in the receipt. It’s a historical scene showing British troops on their way north in 1745 to confront the Jacobite Rebellion, an effort to overthrow King George I. The soldiers are passing through St Giles Circus on Tottenham Court Road. Hogarth paints a comic picture of the state of the British army, showing soldiers flirting with sex workers, gambling and drinking.

The Four Times of the Day, 1738

This series is a tour of London, travelling to Covent Garden, Soho, Islington and Charing Cross. This scene shows French Huguenots in Soho, one community in an increasingly diverse city. Hogarth also includes a Black man on the left-hand side. Most Black people in London at this time had been trafficked as part of the British trade in enslaved African people. Thousands of people of African heritage lived in the city – some free, some still enslaved.

An Election Entertainment, The Humours of an Election, 1754–1755

Hogarth’s election series criticised the state of democracy with images of bribery, violence and corruption. Here, two candidates standing for election are bribing a rowdy room of potential voters with food and drink.

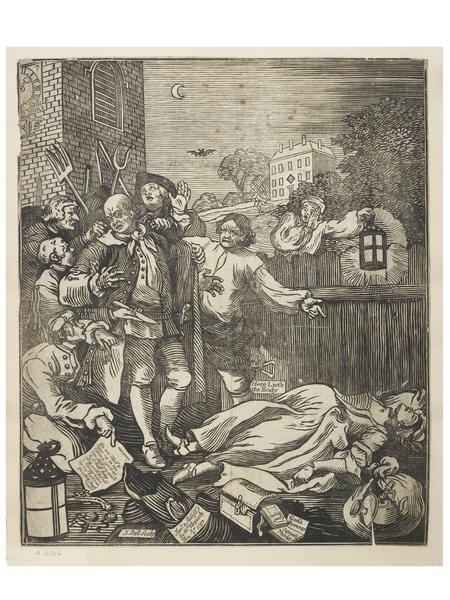

The Four Stages of Cruelty, 1751

This series, wrote Hogarth, was “done in hopes of preventing in some degree that cruel treatment of poor animals which makes the streets of London more disagreeable to the human mind, than any thing whatever”.

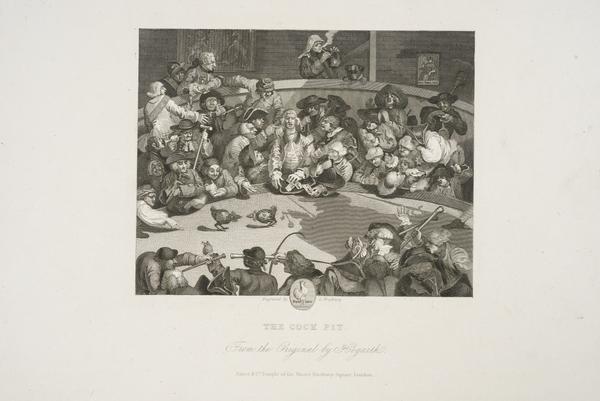

The Cockpit, 1759

This scene shows the Royal Cockpit, located at Birdcage Walk in St James’s. The audience is gathered to watch and bet on cock-fighting, an extremely popular pastime for all classes in 1700s London. Some in the crowd smoke or take snuff, others jostle or steal. A man with a walking stick uses an ear trumpet to hear over the clamour.

John Wilkes, 1763

Hogarth had a huge influence on art, and on our perception of 18th-century London. This overly ugly portrait shows the politician John Wilkes, one of Hogarth’s critics. It influenced satirists like James Gillray, fuelling the popularity of political caricature in the 1700s and the development of comics and political cartoons. Hogarth, though, didn’t consider his art to be caricature. Today, his work is often used to define an age in our city’s history – ‘Hogarthian London’.