Sunil Gupta’s photo-collages protested Section 28

In 1988, photographer Sunil Gupta created a series of photo-collages titled ‘Pretended’ Family Relationships. They protested Section 28, a piece of legislation forbidding the ‘promotion’ of homesexuality. Four of these works are now in our collection.

1988

Poetry, photography and protest

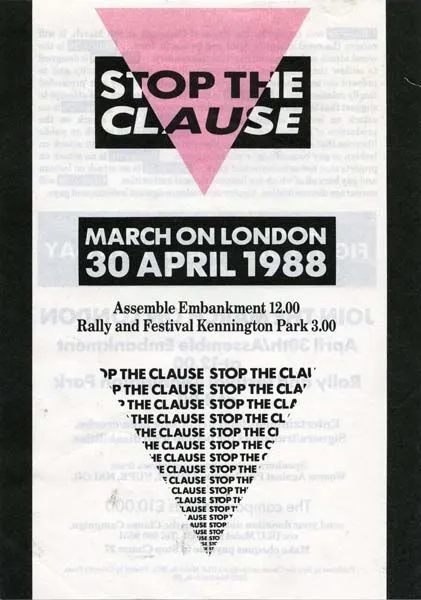

In 1988, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government passed a law banning schools and local councils from promoting “the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”. The legislation was Section 28, sometimes known as Clause 28. It was in place in Scotland until 2000, and England and Wales until 2003.

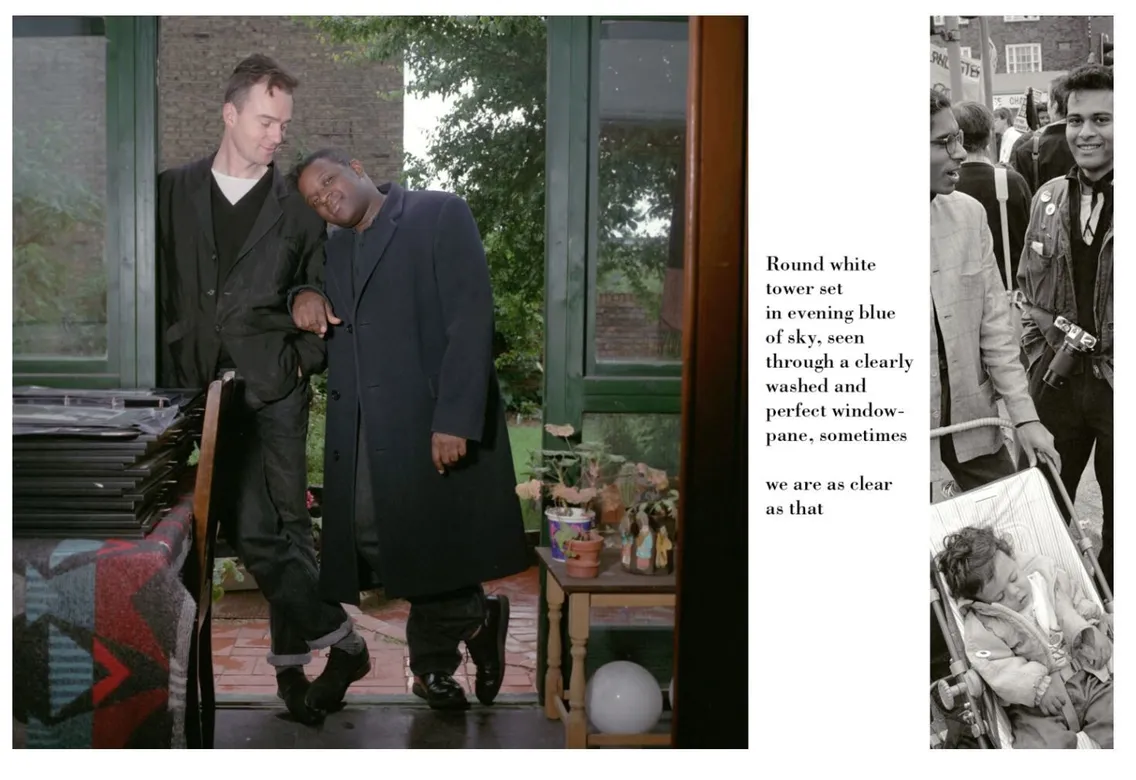

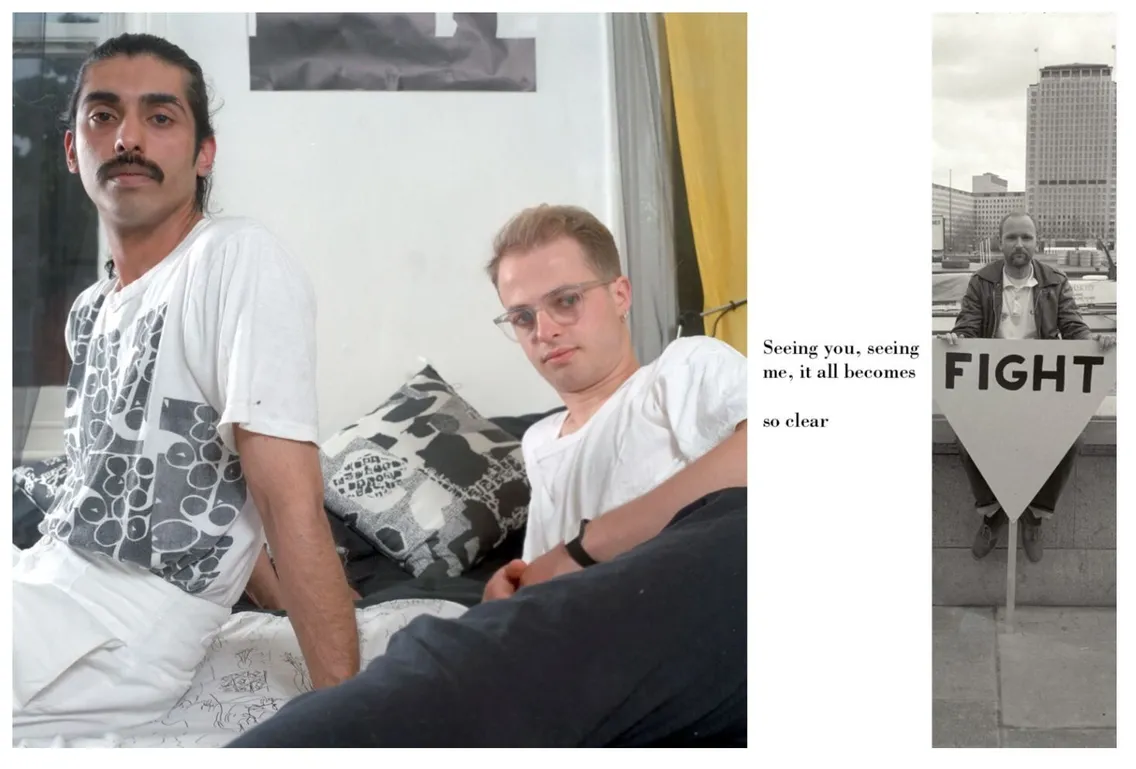

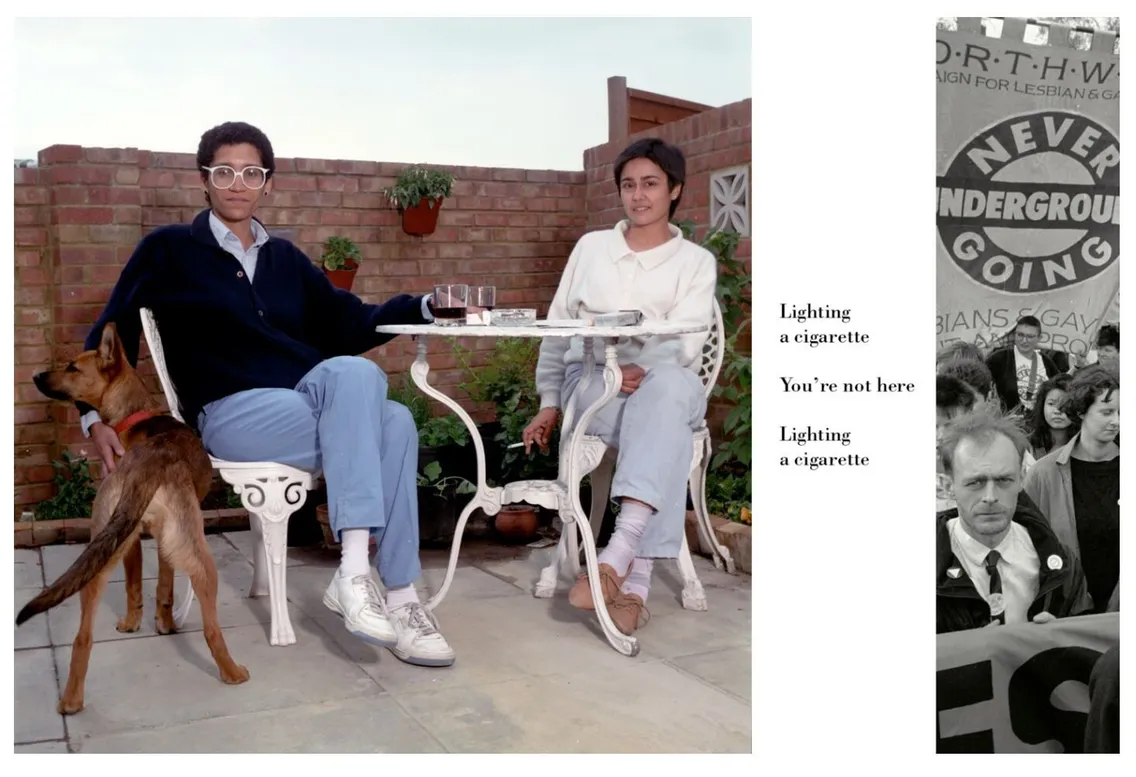

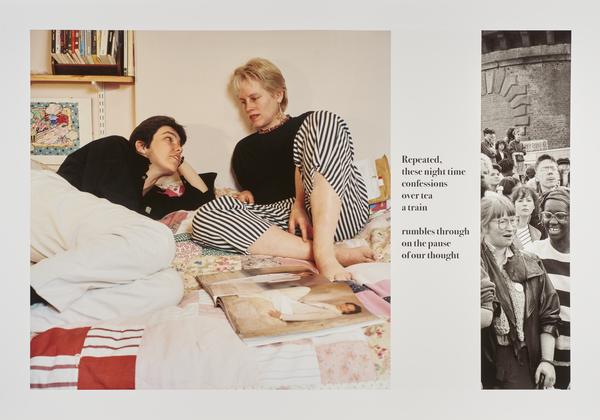

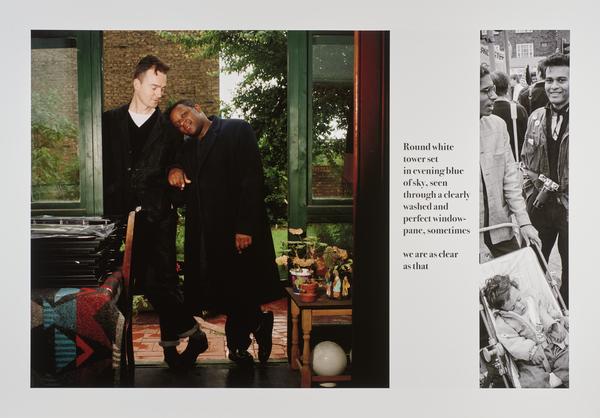

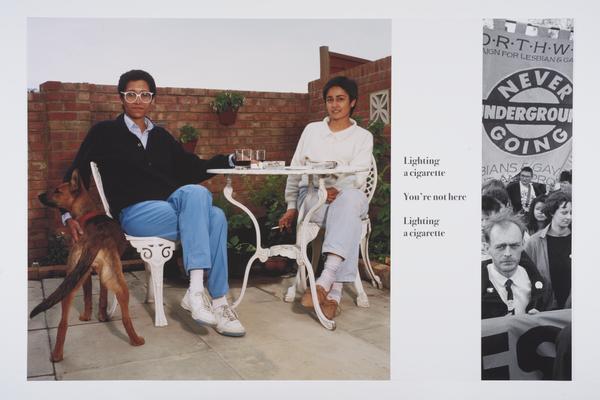

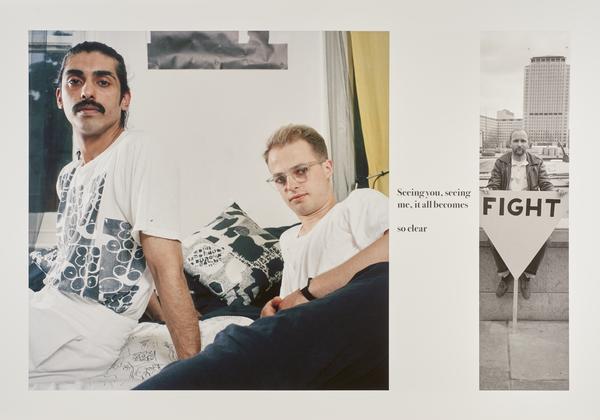

Photographer Sunil Gupta responded to the discriminatory new law with photo-collages. Each work brought together portraits of mixed-heritage same-sex couples, lines of poetry and imagery taken at protests against the law.

He named the series ‘Pretended’ Family Relationships, confronting the wording of a ruling that erased his identity as a gay man by asserting his relationships weren’t real or valid.

Gupta’s project started with partnerships like his

The series was born before Section 28 was passed, when Gupta started taking colour photos of same-sex couples – “that reflected my own situation”, he said in an issue of Tate Etc. magazine. The portraits show couples relaxing at home, or out and about in London.

“It was a time of intense activity around things I really cared about,” Gupta said. In the late 1980s, Gupta was working to co-found the Association of Black Photographers, now called Autograph ABP, that supported marginalised photographers in Britain. From 1986 to 1987, Gupta lived in his hometown of New Delhi, India. He created the series Exiles, photographing gay men at a time when homosexuality was criminalised and punished by imprisonment in India.

The photo-collages feature lines of poetry

Gupta’s partner at the time, Steve Dodd, was living abroad, and the pair would write letters to each other. Dodd often sent Gupta short-form, Japanese-style poems. Gupta decided to incorporate the poems into the work.

Dodd’s poetry could be confronting and intriguing. “If anger is a sign of love, our signs have locked like scorpions,” one photo-collage reads. They were also quite purely romantic. Below, this photo-collage in our collection includes text saying: “Seeing you, seeing me, it all becomes / so clear.”

The project changed direction after Section 28

The 1988 Local Government Act, which contained Section 28, was passed on 24 May 1988 – despite a huge protest movement that had mobilised across the country.

The law had an immediate and devastating impact on LGBTQ+ communities. Section 28 ordered that a local authority should not “intentionally promote homosexuality”, a wording that was all-encompassing enough to impact every aspect of LGBTQ+ people’s lives.

It essentially legitimised homophobia and discrimination, fuelling an already hostile environment and forcing people to hide their identity. Within publicly funded organisations, especially schools, it created a climate of fear around discussing homosexuality.. A generation of young people weren’t given support or proper education on LGBTQ+ issues as a result. Many public libraries removed LGBTQ+ books and press from their shelves.

Gupta joined demonstrations against the law in London, bringing his camera with him. He decided to incorporate the black-and-white photographs from the protests into his evolving body of work. You can see small slivers of these on the right-hand side of the photo-collages. Above, protesters hold up a large protest banner saying “never going underground”.

‘Pretended’ Family Relationships

Together, the photo-collages form a subtle yet impactful protest against Section 28. The relaxed portraits of the couples contrast with the cropped, creeping presence of the protest photos, where people were demonstrating for their right to exist.

The works are all untitled. We don’t know anything about the couples pictured – their names, how they met, their hopes for the future. This anonymity adds to the power of the series and nods to just how widespread the impact of Section 28 was.

The series continues to be exhibited in museums and galleries today. “Looking back,” Gupta reflected in Tate Etc., “perhaps this work has suddenly become more visible because we are, once again, living in such polarised times.”