The Sidney Street siege: An East End shootout

Over six hours on 4 January 1911, soldiers and police officers traded gunfire with two suspected murderers taking cover in an East End house. Also called the Battle of Stepney, it was a dramatic end to a story that gripped Londoners.

Sidney Street, Tower Hamlets

4 January 1911

Gunfire in the East End

On 17 December 1910, three police officers were shot dead while responding to a robbery in Houndsditch, on the north-eastern border of the City of London. The culprits were a group of Latvian revolutionaries.

Two weeks later, on 4 January 1911, two of the group were traced to a house on Sidney Street, in London’s East End. As police surrounded the hideout, a shootout began.

The army was called in to help, joined on the scene by the home secretary, Winston Churchill. Large crowds watched in amazement. The siege only ended when a fire consumed the building and the men’s charred remains were recovered.

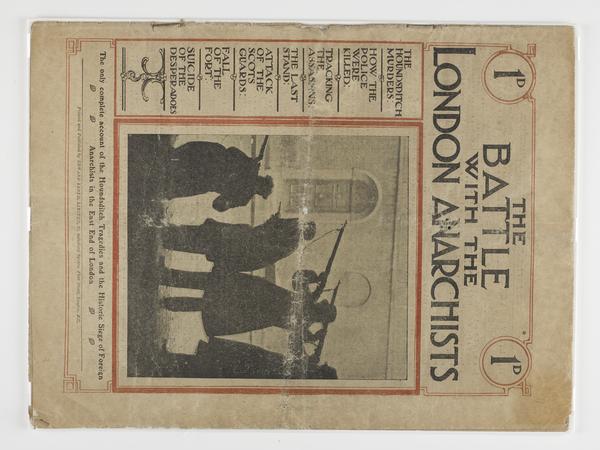

The murders and the siege were must-read news, amped up by sensationalist reporting that often focused on the men being foreign ‘aliens’. It was also one of the first major news stories captured on film.The night after the siege, footage of it was shown at the Palace Theatre in London’s West End.

The Houndsditch murders

On 16 December 1910, several City of London police officers responded to reports of a break-in at a jeweller’s shop in Houndsditch.

When the unarmed officers went inside, the robbers fired at them with their pistols. Three officers were killed and two were badly injured, leaving them permanently disabled. None of the robbers were arrested, though one was killed by a stray bullet.

The officers’ funeral was held on 22 December 1910. The procession was watched by large crowds as it headed to Ilford Cemetery in Redbridge, east London.

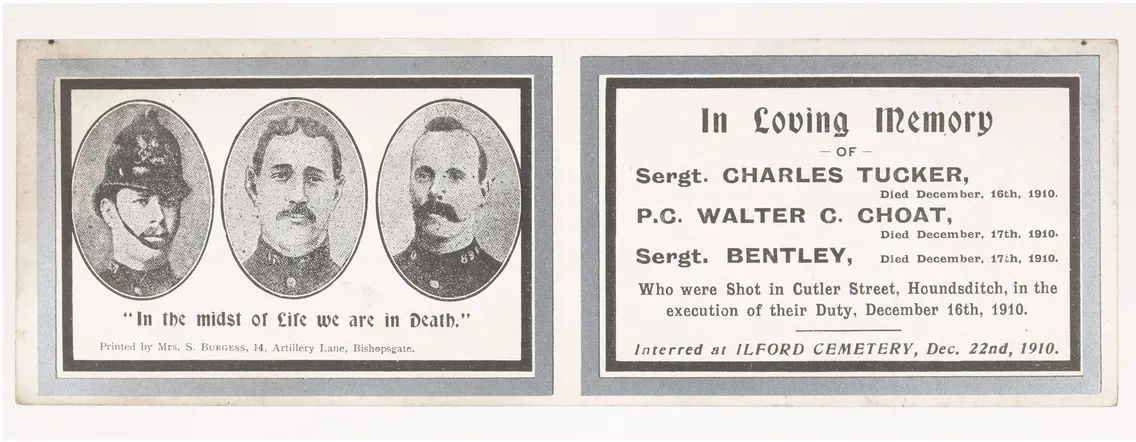

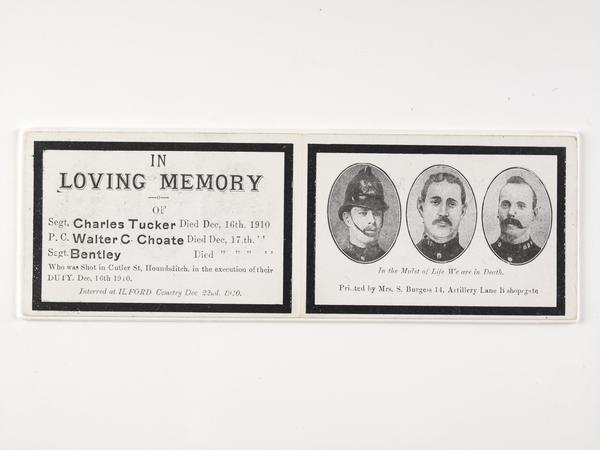

Our collection includes a printed memorial card sold by a street trader at the funeral. It contains the officers’ portraits and their names: Charles Tucker, Walter Choate and Sergeant Bentley.

Who were the suspects?

There had been four men at the break-in. One, George Gardstein, was killed during the robbery. The others escaped.

Two of these were the men later involved in the Sidney Street siege: Fritz Svaars and William Sokolow, better known as Joseph.

Svaars and Sokolow were revolutionaries from Latvia, which was then part of the Russian empire. They’d fled the country after a failed attempt to overthrow the Russian tsar in 1905. Robbing the jewellers was an effort to raise funds for their cause.

The police offered a £500 reward for information, around £50,000 today. They named Svaars as a suspect, alongside someone with the nickname ‘Peter the Painter’. Both were labelled as “anarchists”.

Anarchism is a political ideology that rejects the need for a state or centralised government. But in this period, ‘anarchists’ was the common catch-all term for revolutionaries, used in a similar way to how ‘terrorists’ is today.

‘Anarchists’ were the bogeymen, the figure of fear, of the early 20th century. But there was real reason for concern in London.

In 1909, a different pair of Latvian revolutionaries attempted an armed robbery of a rubber factory in Tottenham. The police chase that followed left a police officer and a schoolboy dead. Another 27 people were injured, and both revolutionaries shot themselves to avoid capture. It became known as the Tottenham Outrage.

What happened at the Sidney Street siege?

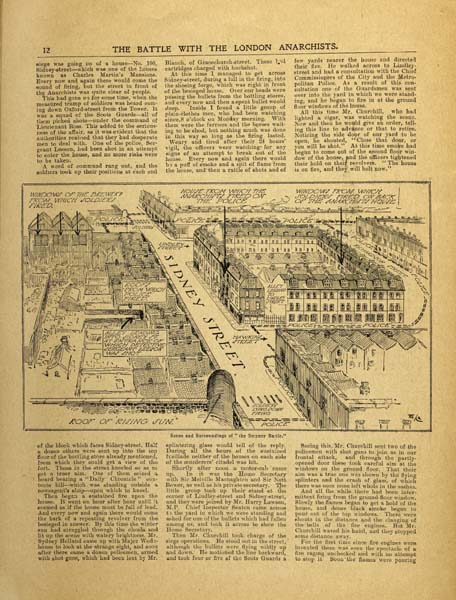

After the Houndsditch murders, it took until the new year for the police to track down their suspects. A tip-off led them to 100 Sidney Street in Stepney, Tower Hamlets.

Police evacuated the building in the early hours of 3 January. Hundreds of officers surrounded the house and blocked off the street. At around 7.30am, the two men inside began firing at the police using their modern Mauser pistols. The police, armed with older rifles and revolvers, were outgunned and pinned down.

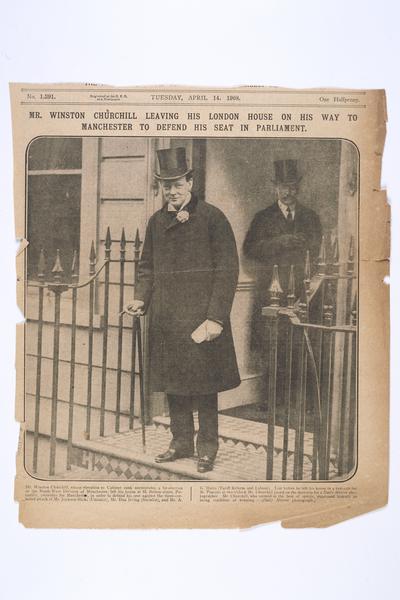

The future prime minister Winston Churchill, then the home secretary, heard about the escalating situation while in the bath. He gave permission to deploy the army.

Unable to resist the opportunity to be at the heart of the action, Churchill headed there himself to find out more. He was later criticised for recklessly putting himself in danger.

“It seemed as if the whole of London had poured into Whitechapel and Stepney”

Daily Chronicle reporter

Soldiers from the Scots Guards regiment stationed at the Tower of London rushed to the scene. Positioning themselves on the street and in the surrounding buildings, they started firing at the men inside. They even brought a Maxim gun, an early automatic machine gun.

Crowds eager for a view gathered at every entrance to Sidney Street, held back by lines of soldiers and police. Journalists took to rooftops to watch the siege unfold. One from the Daily Chronicle described the scene: “It seemed as if the whole of London had poured into Whitechapel and Stepney to watch one of the most deadly and thrilling dramas that has ever happened in the great city within living memory.”

One detective was hit by a bullet, leaving him with injuries that forced him to retire.

How did the siege end?

Around 1pm, a fire began to burn inside the building holding the revolutionaries. It’s unclear how it started.

The fire grew until it consumed the whole building. "They'll be fried like rats in an oven," said someone watching. Churchill ordered firefighters not to intervene.

The ceiling, then the roof, collapsed, and the bodies of the two revolutionaries were later discovered inside. As firefighters moved in to search the gutted building, one was killed by falling rubble.

Immigration and the East End’s criminal reputation

Several people were put on trial in connection with the Houndsditch murders, but none were found guilty.

The Daily Mail newspaper gave this verdict: “The police can hardly be congratulated upon their success in dealing with this formidable conspiracy; but, in excuse, it must be remembered that in the vast alien population of East London it is a matter of peculiar difficulty to obtain evidence or run down the offender.”

Writers, journalists and artists often portrayed the working-class East End this way. They painted it as a haven for criminals and blamed this on its large population of migrants.

The East End was close to London’s docks, so its community was in constant flux. Seamen from across the world stopped there temporarily. Refugees also settled there, staying close to where they’d stepped off their ships. This ever-changing population caused fear and distrust, and ‘foreign aliens’ were often wrongly accused of crimes.

Coverage of the Sidney Street siege also included the common stereotype that the East End was an overcrowded warren of narrow streets and bad housing, overwhelmed by poverty.

This was despite the improvements made there by the early 20th century. By 1911, Sidney Street had been widened and modernised, although slum housing remained in the surrounding area.