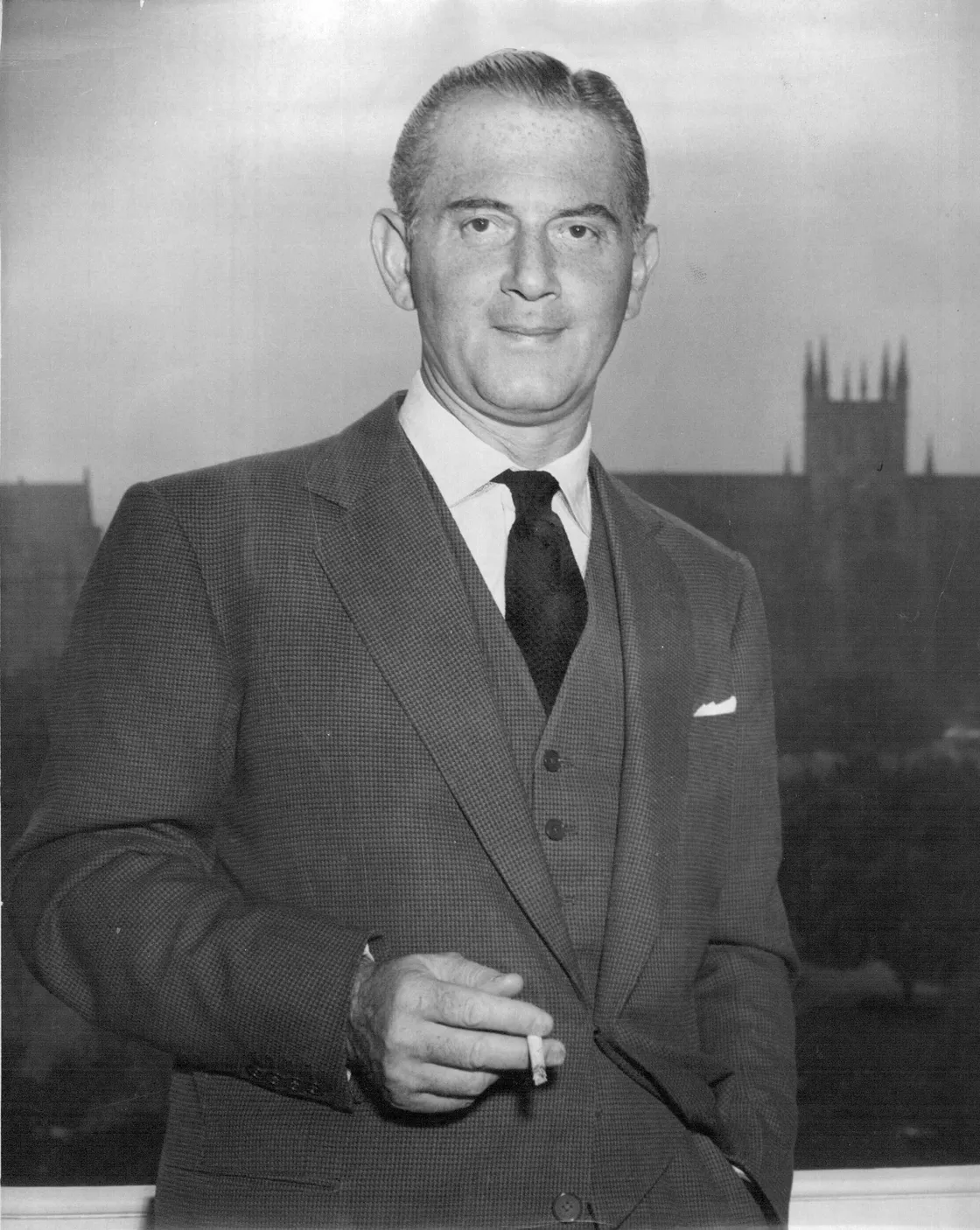

Otto Lucas put London on the hat-making map

This milliner, a maker of women’s hats, isn’t well known today. But Otto Lucas’ eye for chic, modern design and shrewd business mindset made him a mid-20th-century fashion sensation.

City of Westminster

1903–1971

The millionaire milliner

Otto Lucas hats were must-have items for the rich and famous. His company’s designs graced the cover of the prestigious British Vogue magazine at least 10 times. And they were stocked in high-end stores like Harrods and Fortnum & Mason. So why isn’t Otto Lucas a household name?

This German-born, internationally-renowned businessman transformed London into a new centre for women’s hat-making, or millinery. His life story is rich and fascinating. Yet he was also a very private person, a gay Jewish man who lived during a time of Nazi antisemitism and criminalised homosexuality.

The people who worked for him have helped to record his legacy since his tragic death. But Lucas deserves his slice of the spotlight. He was a key figure in London’s fashion history.

Lucas sets up shop in London

After learning millinery in Paris and Berlin, Lucas moved to London in 1932 and founded his business, Otto Lucas Ltd. The company moved from Old Cavendish Street in Marylebone to its permanent location at 87–91 New Bond Street, Mayfair, a few years later.

While Lucas didn’t make the hats himself, he was ambitious, creative and hired the very best in hat-making talent. The New Bond Street workroom buzzed with workers skilled in various elements of hatmaking, from design to finishing labels and trimmings. It could take between five and eight hours to finish just one hat.

He endured tough times during the Second World War

Adolf Hitler’s fascist Nazi Party gained power in Lucas’ home country, Germany, in 1933, leaving Lucas effectively stranded in London. As a gay Jewish man, it would be too dangerous for him to return.

The Second World War began in 1939, and four years later, his parents were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp in German-occupied Poland. They were both killed there.

Lucas still faced significant challenges in his new home. He had, according to fashion designer Hardy Amies, “settled into the London scene as comfortably as his thick accent would allow”. But after war broke out, all German and Austrian nationals living in Britain were classed by the government as “enemy aliens”, even refugees and Jews like Lucas.

From May 1940, the government arrested around 29,000 of these so-called “aliens” – mostly men, but also some women and children – and held them in camps. Lucas was detained at a camp on the Isle of Man from June to September. We don’t know much about what happened to him there, but documents from his release say he was “invalid or infirm”, suggesting he was weak or ill.

Otto Lucas hats were a post-war sensation

Lucas’ business flourished after the war ended in 1944. His experiments with colour and shape, plus his signature use of flowers, caught the eye of fashion consumers across society.

The artistry of his high-end, made-to-measure Otto Lucas Couture hats, sold from the New Bond Street showroom, made him famous. But the average Londoner would have also known him through his trendy rainwear hats sold in big stores, or his cheaper and fast-selling Otto Lucas Junior line.

Otto Lucas Junior hat.

e also made a name for himself in the United States, and his relationship with buyers there pushed Otto Lucas Ltd. to global success. The Los Angeles Times called him “Bond Street’s mad hatter”, and reported he’d sold 103 hats in two days at the famous New York department store Saks Fifth Avenue.

Where Paris was previously seen as the millinery capital, Lucas had shifted the centre of gravity across the English Channel to London.

A luxurious London lifestyle

As his successes brought him wealth, Lucas enjoyed indulging in the finer things in life: champagne, opera and Savile Row suits.

He lived between his London home near Harrods, where he’d stop by and shop after work, and a country manor in Kent. His countryside existence was quieter – picture dinner parties, drawing rooms and gatherings around an open fire. But things were a bit different in the city.

Lucas was a member of the Colony Room Club, an infamous Soho haunt for bohemians, misfits, refugees and artists (most famously, Francis Bacon). He was close friends with the legendary landlady Muriel Belcher, a sharp-tongued and charismatic lesbian whose openness about her sexuality attracted many gay Londoners to her drinking club.

The Colony Room was a haven. It was a place where you could be yourself, away from the homophobia of wider society. This was a time when homosexual activity between men was criminalised until the passing of the Sexual Offences Act of 1967.

Lucas also had close ties with London’s Jewish communities. He was involved in fundraising events for both the Jewish Board of Guardians and the Jewish Welfare Board.

His life was tragically cut short

On 2 October 1971, Lucas was a passenger on a flight from London to Salzburg that crashed into the ground in Belgium. All passengers and crew were killed. Otto Lucas Ltd. closed the following year.

In the last year of his business, it’s thought Lucas sold 55,000 hats. The milliner Philip Somerville, who designed hats for Queen Elizabeth II in the 1980s, trained under Lucas and reflected how “his name was God in the hat world”.

And yet, quickly and quietly, Otto Lucas faded from the London fashion conscience and the publications that once championed him.