The medieval graveyard on Newgate Street

In the 1970s, archaeologists digging at a site in central London discovered the remains of 234 people buried nearly 1,000 years ago.

City of London

1000–1200

The General Post Office once stood on the site of the medieval St Nicholas Shambles church.

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

Delivering the past

In 1974, construction was planned for a site close to where Newgate Street meets King Edward Street, only a stone’s throw from St Paul’s Cathedral.

Between the 1000s and 1500s, a church named St Nicholas Shambles and its surrounding graveyard stood on this spot.

Archaeologists were tasked with uncovering what they could before the bulldozers rolled in. They discovered the graves of 234 people, all buried there between 1000 and 1200.

Adopting new methods to deal with the large number of graves, the archaeologists’ work revealed fascinating details about how these people lived, died and were buried.

The history of the site

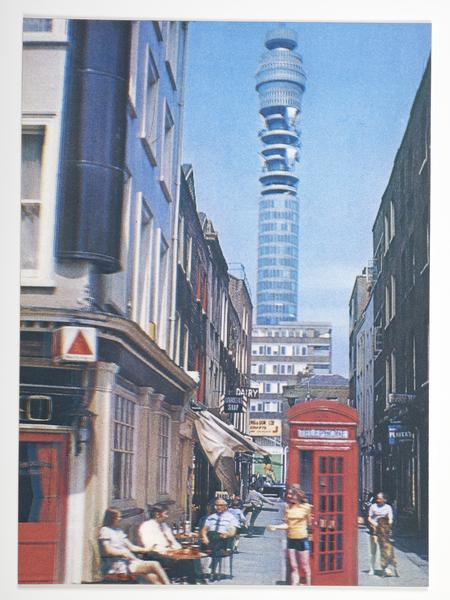

The archaeologists came face to face with these medieval Londoners while digging ahead of the construction of the old BT Centre, which opened in 1984.

Before the BT Centre, the site was home to the General Post Office, London’s main post office between 1829 and 1910.

Long before that, it was home to St Nicholas Shambles. This small parish church was built in the early 1000s and expanded several times before it was demolished in 1552.

Its name is taken from the nearby Newgate Shambles, the slaughterhouse district which once served the Smithfield livestock market.

The church’s graveyard was the first to be excavated on a large scale within the City of London.

As is often the story in London, the old BT Centre has since been redeveloped into an office building.

Time pressure leads to new methods

The archaeologists digging in 1974 only had limited time to investigate and record the ground before construction was scheduled to begin.

For this ‘development-led’ archaeology, those working on the site had to quickly develop new ways of recording the mass graves in enough detail.

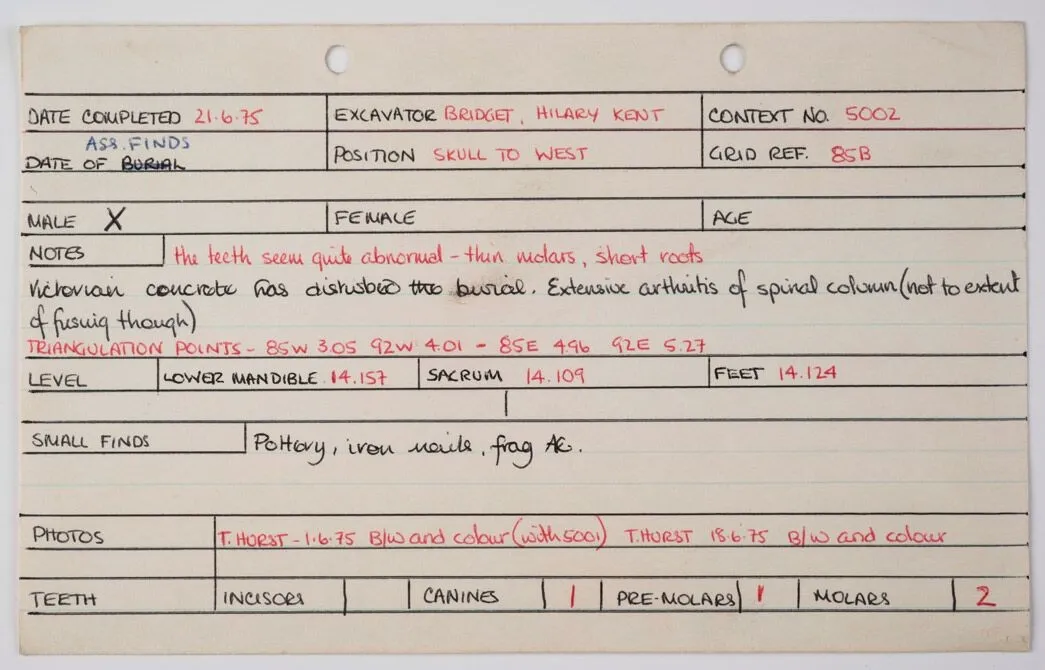

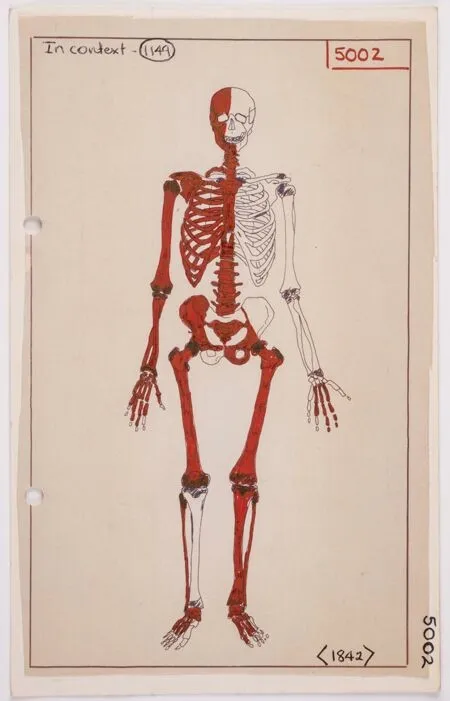

They used recording sheets made specifically for skeletons. These standardised how the archaeologists described what they found, allowing for better comparisons to be made later on.

The back of a skeleton recording card.

They took photos on site, so that they could painstakingly draw each grave at a later date.

And nifty ways of lifting and bagging the bones saved time during lab analysis. The left and right side of the body was bagged separately, as were the small bones of the hands and feet. Some of their techniques aren’t used by archaeologists anymore, such as stringing the spinal bones together before lifting them.

The front of a skeleton recording card indicating which bones were found in each grave.

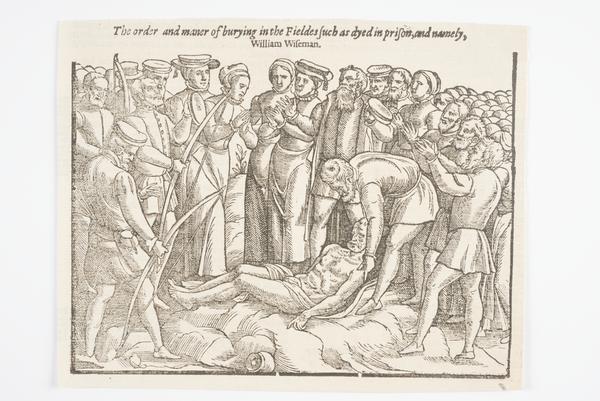

How were these medieval people buried?

Archaeologists were able to establish that the people at St Nicholas Shambles were buried in five different ways.

The vast majority were buried simply. Nails, fragments of wood and scraps of cloth suggested the people were wrapped in shrouds within wooden coffins – most of which had rotted away.

Some people were given stone pillows or placed in stone-lined chambers. Others were laid on floors of crushed chalk and mortar, possibly to soak up oozing bodily fluids produced during the process of decay.

In just one case – the burial of a child – charcoal was used to line the grave and was placed on top of the body.

These different burials offer us tantalising insights into the people’s beliefs, their Christian faith and the funeral ceremonies that their loved ones carried out.

Charcoal, for example, was associated with purity and believed to protect the body. Charcoal and ashes were also linked to the Christian idea of penitence, the expression of remorse for doing wrong.

“75% of the adults had calculus on their teeth, a form of hard plaque caused by a lack of scrubbing”

Studying the bones

Detailed examination by bioarchaeologists, who study excavated human bones, provided insights into the health of the population at the time of these burials.

One of the few skeletons in the cemetery with tooth decay.

Teeth can tell us so much about people’s health. Bioarchaeologists found that 75% of the adults had calculus on their teeth, a form of hard plaque caused by a lack of brushing.

This is commonly seen on the teeth of medieval people. It sometimes led to chronic gum disease, which caused teeth to loosen in the jaw. But tooth decay and abscesses were far less common than today because of their low-sugar diet.

A blow to the head

One small fragment of a skull gives us an insight into a violent event that happened more than 800 years ago.

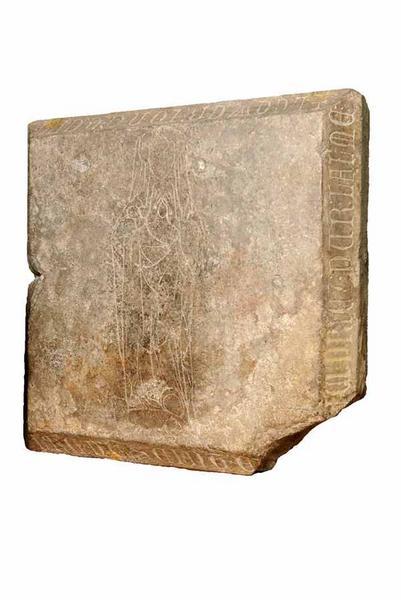

A fragment of skull found at the site.

We can see from this piece of skull bone that this person, a man aged between 17 and 25, received a nasty blow to the head. The shape of the wound suggests a sword was the culprit. The position of the blow tells us that the person was attacked from behind, and the angle of the cut suggests the attacker was right-handed.

Amazingly, this wound may not have proved immediately fatal, as the blade did not cut through the full thickness of the bone. However, as we can’t see any signs of the surrounding bone healing, the victim probably didn’t survive for very long after the attack.

This is an edited version of an article by Lucy Creighton, Archaeology Collections Manager.