Lost London buildings by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd

For a record of London’s landscape in the first half of the 1800s, and a glimpse of buildings lost to time, try the work of Thomas Hosmer Shepherd. His drawings and watercolours, many of which are in our collection, filled books documenting the city’s newest constructions, grand interiors and busy streets.

Across London

1793–1864

East India House, City of London

Shepherd’s first known work is a drawing of East India House. He made it when he was 16 for Rudolph Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, an arts magazine. East India House, on Leadenhall Street, was the headquarters of the East India Company. Founded in 1600, the company went from trading to conquering in India, eventually seizing control of much of South Asia for the British empire. The building was demolished in 1862.

Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was built for the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851. Its glass and iron structure was later moved to what’s now Crystal Palace Park, but burned down in 1936. Shepherd belonged to an artistic family. His elder brother, George Sidney Shepherd, also drew buildings and streets. And Thomas’ two sons, Frederick Napoleon and Valentine Claude, continued his artistic legacy.

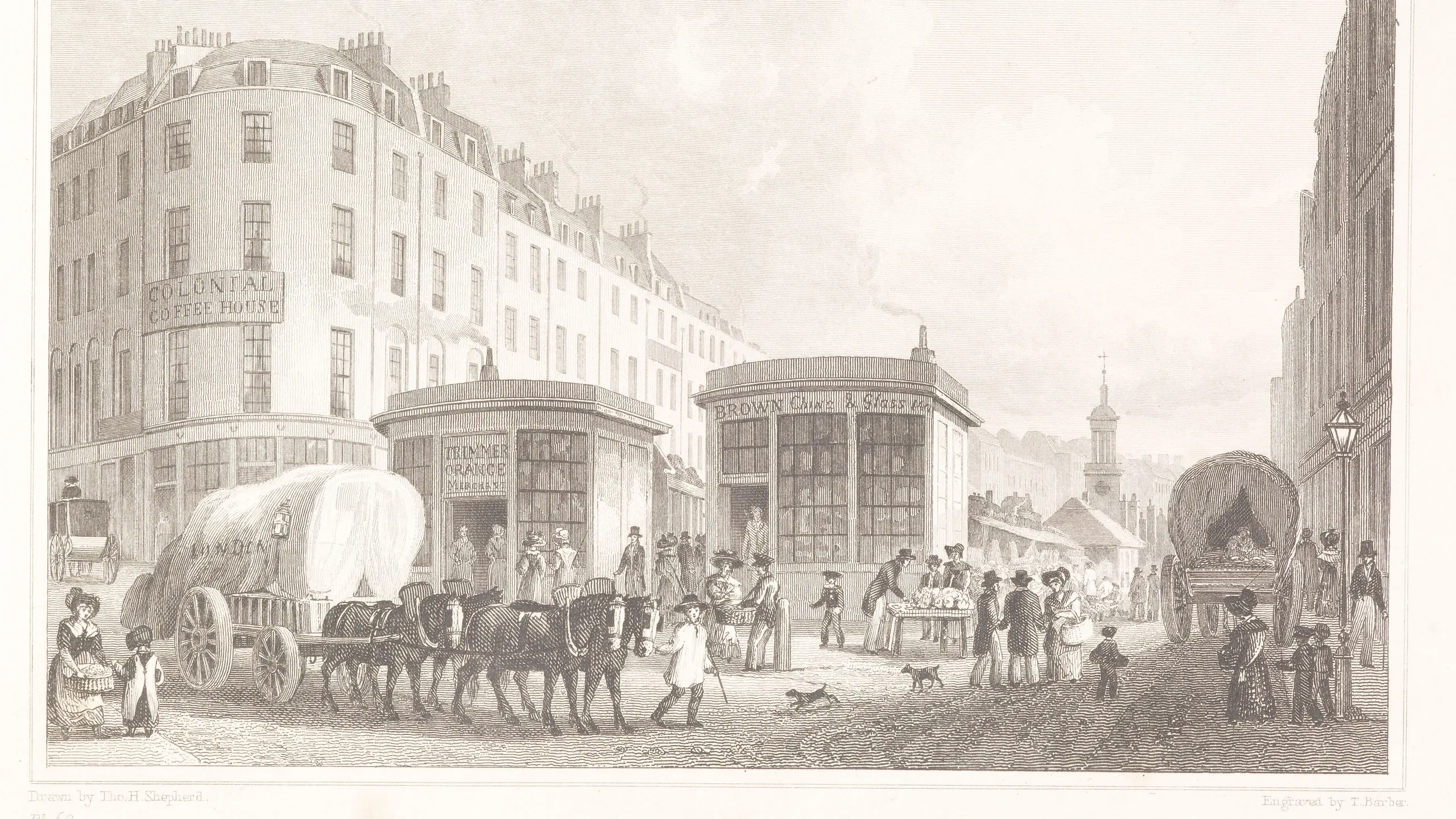

Fleet Market, City of London

Fleet Market was a covered meat and vegetable market built over the River Fleet in the 1730s. It was demolished in the 1820s to make way for Farringdon Street. Shepherd’s image captures the bustle of everyday city life – something typical of his work. A black dog or two, often prancing about under the feet of people and horses, frequently served as a kind of signature.

Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly

This exhibition venue was built in the 1810s to hold historical artefacts and artworks. A visit might include a sight of French emperor Napoleon’s bulletproof carriage or a mammoth skeleton. The hall was demolished in 1905, but the two statues of Egyptian gods from the facade are part of our collection.

Cure’s College Almshouses, Southwark

Shepherd drew many of London’s almshouses, where elderly or poor people were given a home. Look closely at this watercolour and you’ll see that one of the gravestones is marked "T.H Shepherd" with the year "1852".

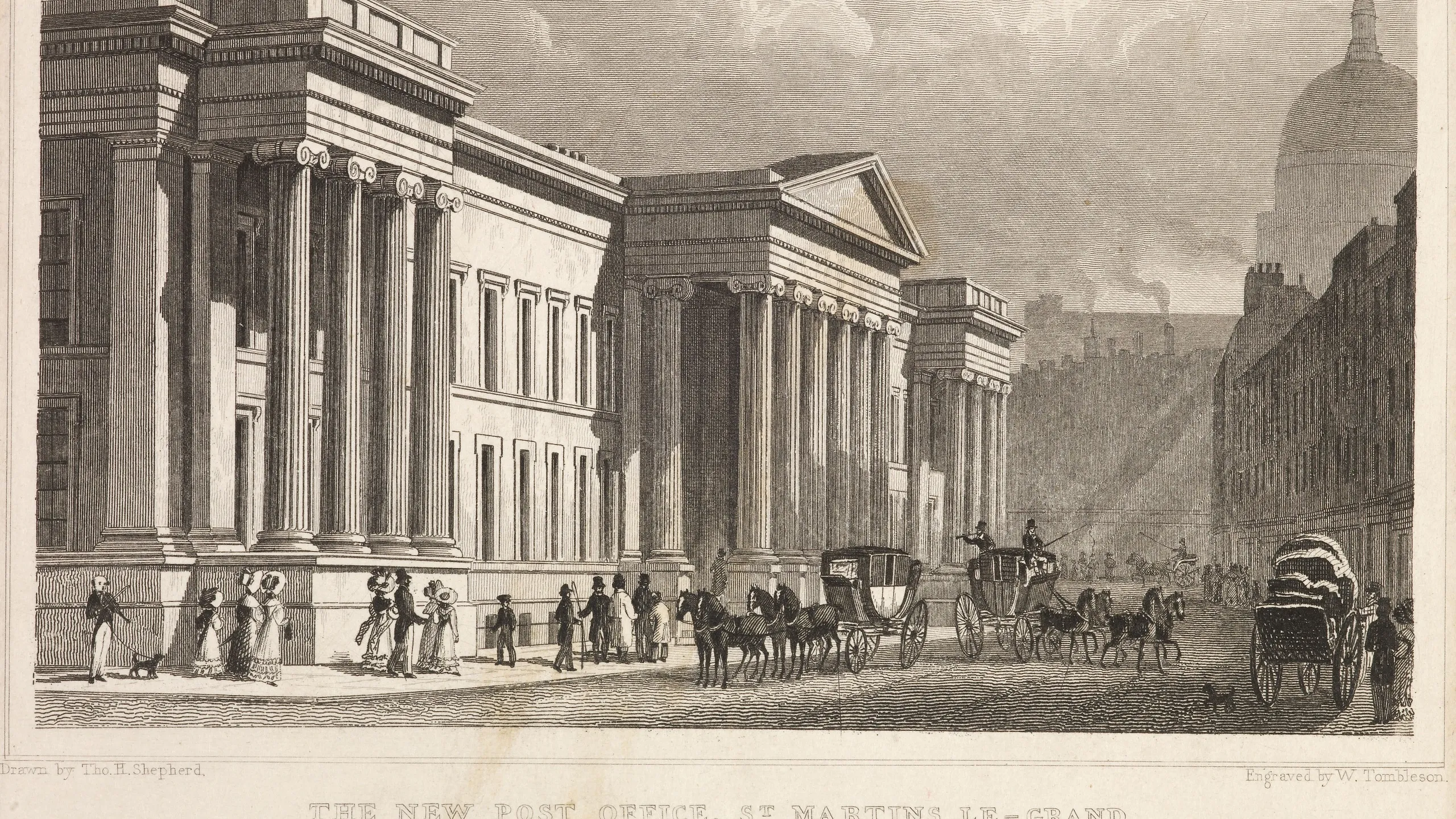

Post Office, St Martin’s le Grand

Shepherd presents London as a bustling commercial metropolis where the old and new sit side by side. Here, the timeless silhouette of St Paul’s looks down on the new Post Office, opened in 1829. The building served as a post office, sorting office and the base of operations for the organisation. It was demolished in 1912.

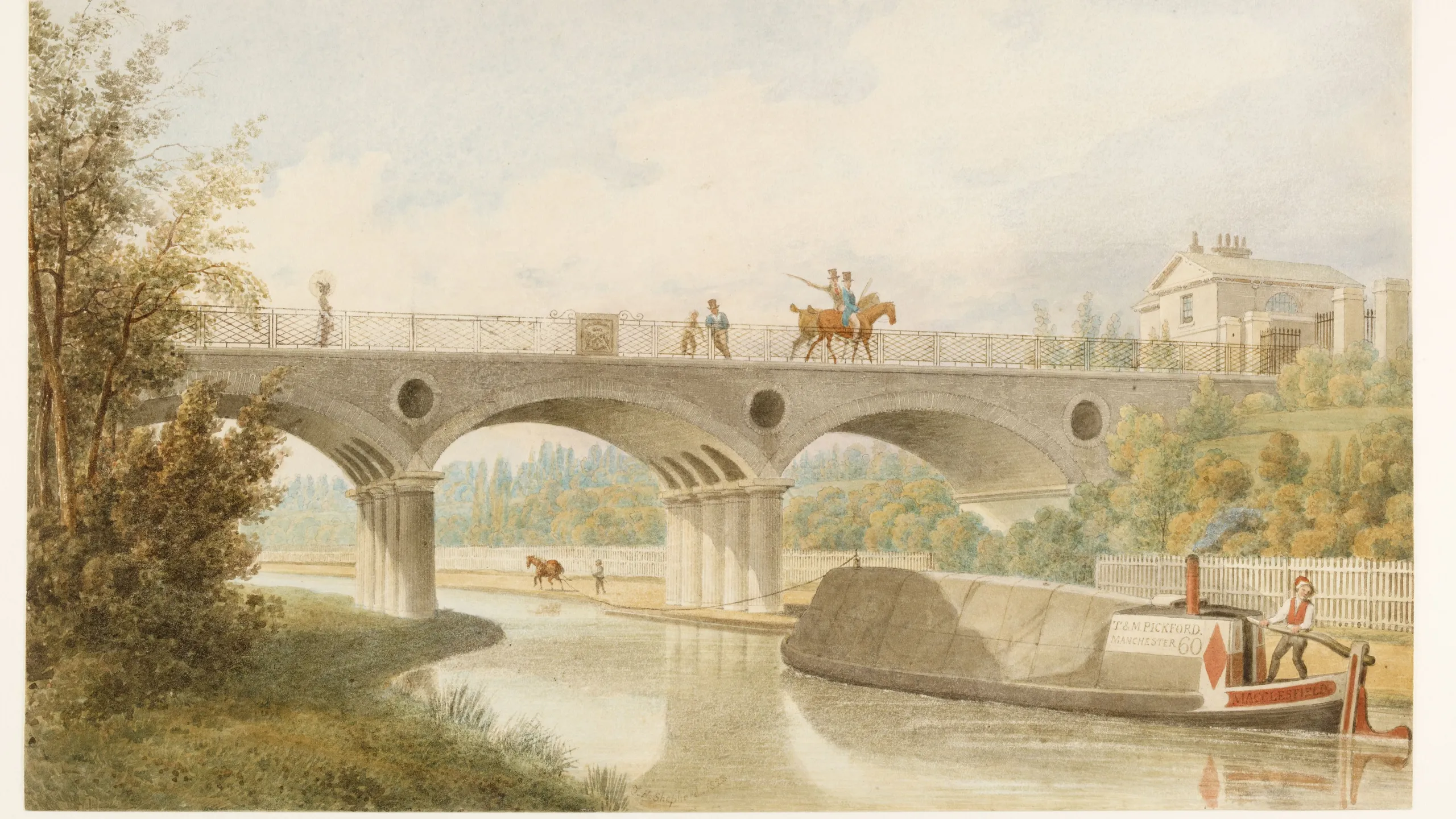

Macclesfield Bridge, Regent’s Park

Although there’s still a Macclesfield Bridge that crosses Regent’s Canal in Regent’s Park, it’s not the same one we see here. The previous bridge was destroyed in 1874 when a barge carrying gunpowder exploded as it passed below. Three men and a boy died in the accident.

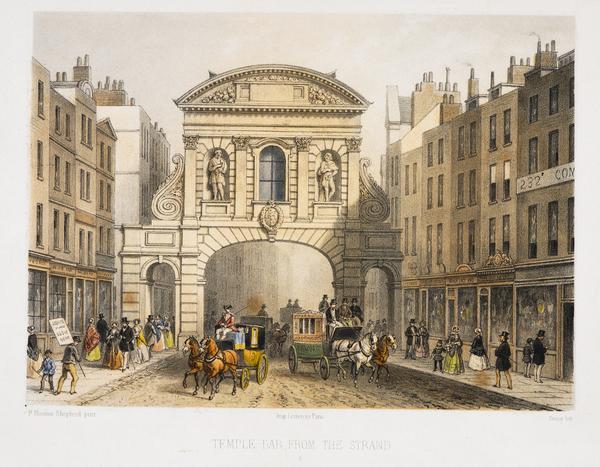

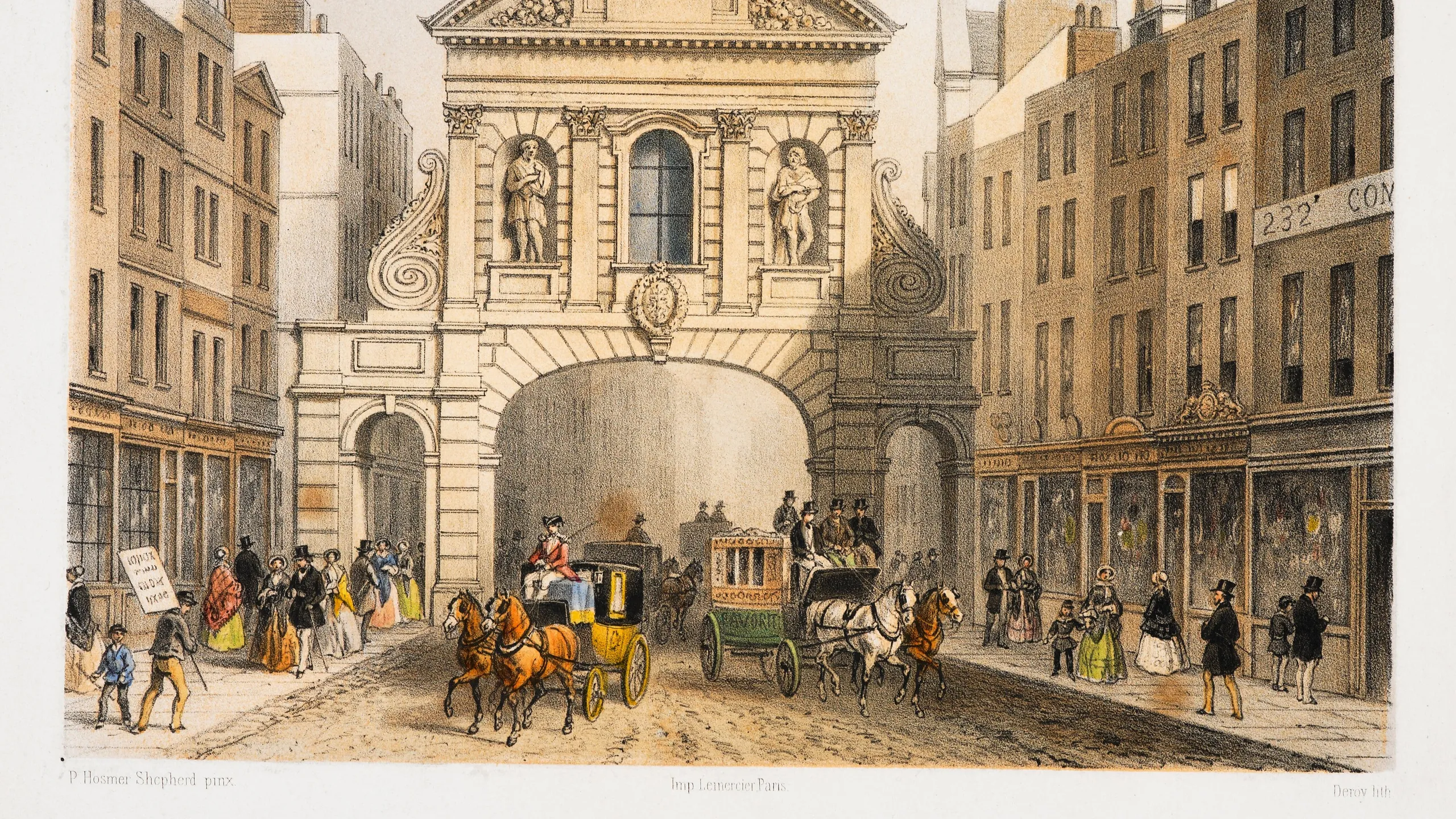

Temple Bar, Strand

Temple Bar was a gateway between the Strand and Fleet Street, marking the western boundary of the City of London. It was rebuilt in the 1670s, probably from a Christopher Wren design, producing the arch shown here. In 1878, it was removed to ease congestion and re-erected in Hertfordshire. But the stones returned home to London in 2004 when the arch was rebuilt in Paternoster Square.

Foundling Hospital, King’s Cross

The Foundling Hospital was a home for abandoned children. After moving several times, a new hospital, drawn here by Shepherd, was constructed on Lamb’s Conduit Fields in the 1740s. Our collection of Shepherd’s work includes watercolours and ink-wash drawings like this, as well as prints and engravings based on his work.

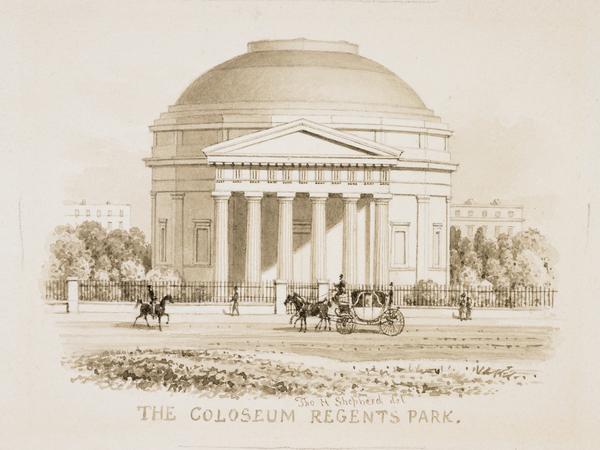

The Colosseum, Regent’s Park

The Colosseum was built in 1827 to house panoramas, enormous paintings displayed on a circular wall to immerse and amaze viewers. The building was demolished in 1875.

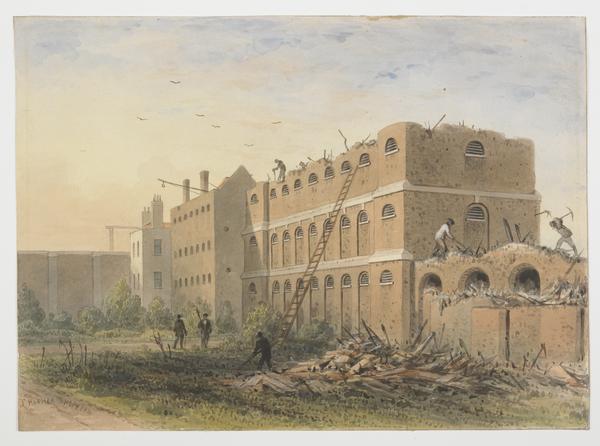

Clerkenwell House of Correction

Shepherd made a set of watercolours of this prison shortly before it was demolished. He’s mainly valued for his architectural detail and accuracy, which makes his work a useful historical source. But the characters he adds bring his subjects to life for us 200 years later.