The lost, lawless tradition of Shrovetide football

Football’s origins stretch back to medieval times, but it was a totally different ball game back then. Shrove Tuesday matches were one example of a chaotic and disorderly sport that was banned many times over hundreds of years.

Across London

1100s–1800s

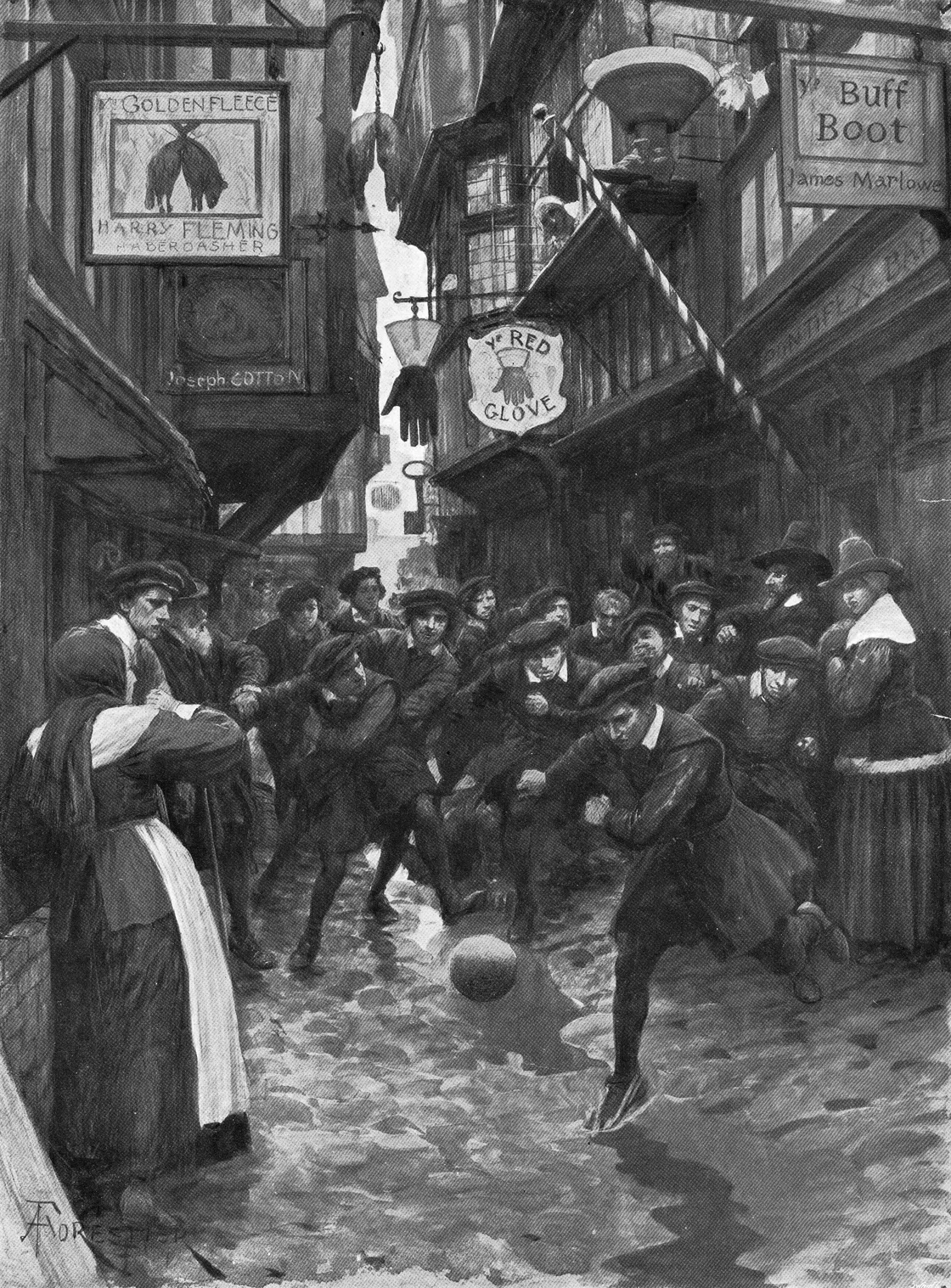

Football being played in the 14th century.

Bans, brawls & broken bones

Football might not be the first thing you think of when you think of Shrove Tuesday. This Christian day of feasting and celebration is more commonly associated with the custom of eating pancakes.

But for hundreds of years, people across the country would take part in a raucous event we’ve come to call Shrovetide football. It was one part of a wider historic ballgame known today as mob football or folk football, which was played throughout the year.

While the game played at Shrovetide had some similarities to modern football, it involved fewer rules, many more people and much more violence.

The event was huge in the City of London and towns like Kingston upon Thames. Shrove Tuesday was known to many Londoners simply as ‘Football day’.

The tradition has long disappeared from London’s streets, but thousands still gather in the town of Ashbourne in Derbyshire for the Royal Shrovetide Football match every year.

When did Shrovetide football start?

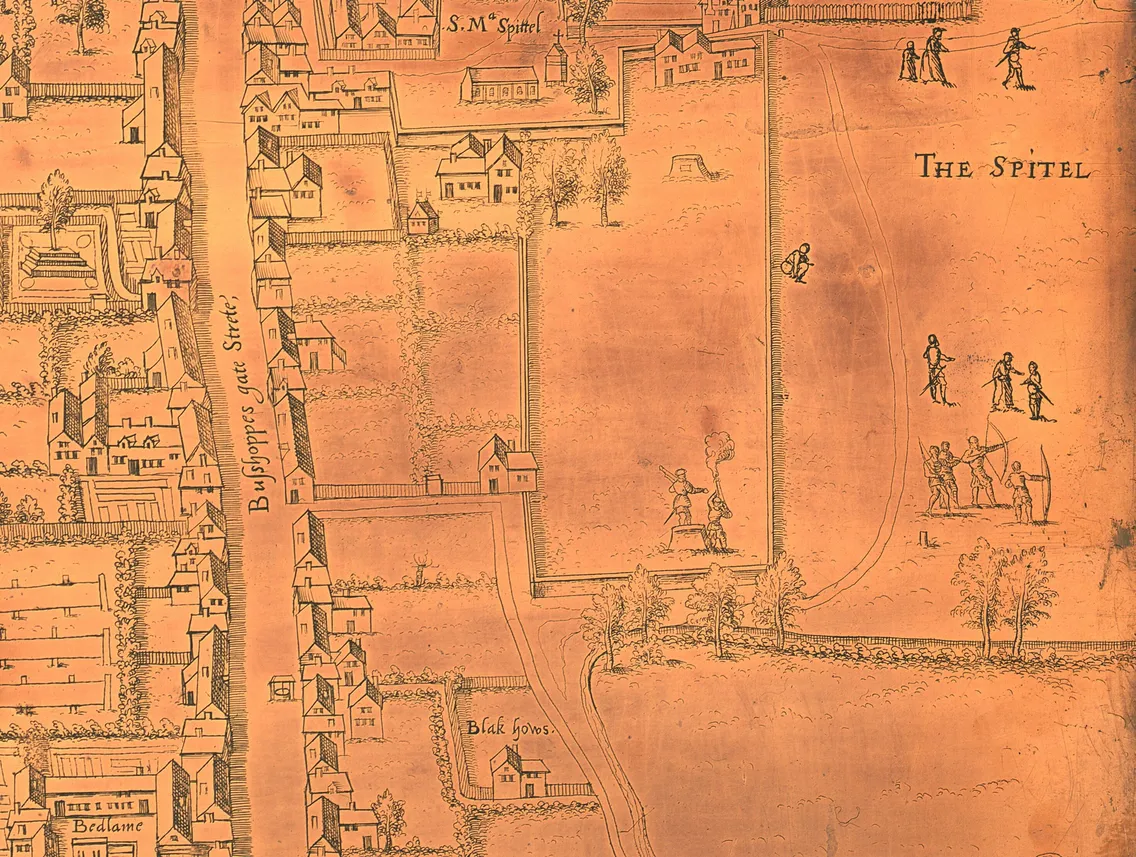

We don’t know exactly when this tradition began. The earliest description of an organised ball game in London dates back to medieval times.

William Fitzstephen, the biographer of the English archbishop Thomas Becket, wrote about a ‘ball game’ on Shrove Tuesday in around 1174: “After lunch all the youth of the city go out into the fields to take part in a ball game. The students of each school have their own ball; the workers from each city craft are also carrying their balls.”

His Latin text has been reinterpreted and re-translated many times. But we can gather that it was played by schoolboys and young men in fields outside the city walls.

Fitzstephen also commented on how it was a popular spectator event: “the elders of the city, the fathers of the parties, and the rich and wealthy, come to the field on horseback, in order to behold the exercises of the youth.”

“There rose amongst them a great affray likely to result in homicides and serious accidents”

Report of a football game in 1576

What did Shrovetide football look like?

Forget 11-a-side on a marked pitch. Before football was standardised in the 1800s, this ball game was large and lawless. There were two teams and two ‘goals’ – but that’s where the similarities come to an end.

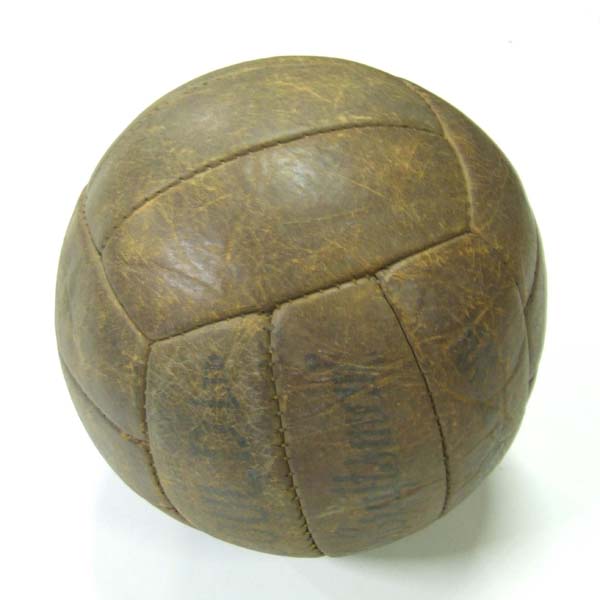

The goals could be marked by something as simple as a post or local landmark. The ball was usually made from an inflated pig's bladder. You could kick it, but you could probably also hold it or hit it with sticks. Modern rugby, for example, developed from folk football.

Shrovetide football didn’t have limits on how many people could play on a team. It could be one village against another. The Middlesex County Records has a report of one 1576 game involving six men from Ruislip, eight from Uxbridge and “unknown malefactors to the number of a hundred”. It goes on to say that “There rose amongst them a great affray likely to result in homicides and serious accidents.”

The game didn’t really have any rules. It could be played in fields and even in the streets. And there were no referees. Broken windows and broken bones were common as the sides fought – often quite literally – for victory.

There are even instances of players being killed during a match. In 1581, a man from Middlesex called Roger Ludford died after being struck in the chest by the elbows of two rival players, according to the coroner's records.

When London banned football

In 1314, King Edward II banned the ball game within the City of London. The royal order cited “great uproar in the City through certain tumults arising from the striking of great foot-balls in the fields of the public… from which many evils perchance may arise”.

The punishment for playing? Imprisonment. This ruling is also thought to be the first recorded use of the word ‘foot-ball’ in English.

Why did Edward ban football? The violence and size of the game concerned the authorities. But Edward was also fighting with the king of Scotland Robert the Bruce, so anti-football legislation was used to help maintain peace and order back home.

“vain games of no value”

1365 statute

Laws against football were put in place in cities and across the country at least 30 more times. The laws often pointed out the disorder of the game. They also ruled that football distracted young men from practising archery – a necessary skill to protect the country.

In 1365, King Edward III ordered the Sheriffs of London to ensure “every able-bodied man” practised shooting with “bows and arrows or pellets or bolts” during their leisure time. These men were forbidden “under pain of imprisonment to meddle in the hurling of stones, handball, football… or other vain games of no value”.

South-west London was a Shrovetide football hotspot

In reality, anti-football laws weren’t properly enforced and mob football persisted in London. The Shrove Tuesday tradition continued well into the 1800s.

Most of the 19th-century Shrovetide games we know of took place in what’s now south-west London, particularly in boroughs like Richmond and Kingston upon Thames.

In 1815, one visitor to Kingston was “not a little amused” to see buildings boarded up in preparation for what he learned was called “Foot-ball day”. He wrote that, “At about 12 o’clock the ball is turned loose… and those who can, kick it”. This was no 90-minute contest: “the game lasts about four hours, when the parties retire to the public-houses.”

“a practice condemned by the good sense of the many”

Surrey Comet, 1866

In 1866, the Surrey Comet reported on the “old custom” of a Shrove Tuesday match in Kingston’s marketplace. It noted the “old scene of closed shops and barricaded windows, of business suspended as if the town had lost its senses.”

After vividly describing a “violent and boisterous” game, the paper called the Shrovetide match “a practice condemned by the good sense of the many” and called for an end to it. The tide had turned on this tradition. The local council banned Shrove Tuesday football the following year.

Football was popular beyond the Shrovetide matches

Football was played in many different forms in London beyond the sprawling Shrove Tuesday matches. The print below from our collection shows football being played on a frozen River Thames during a 1684 frost fair.

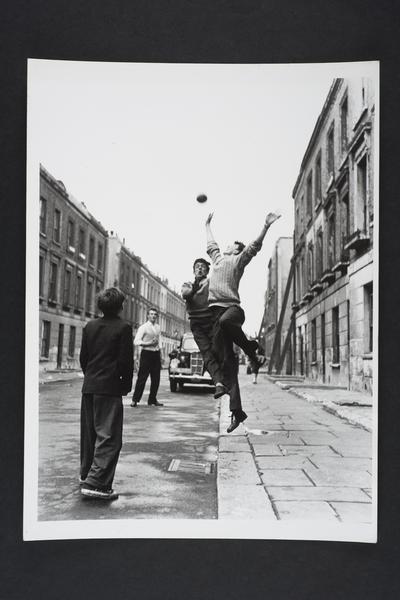

Large mob games were still a feature of London life in the 1700s and 1800s. In his 1716 poem Trivia: or, The Art of Walking the Streets in London, John Gay writes about “the furies of the foot-ball war” in Covent Garden. He describes trying to flee from the growing crowd of players: “But wither shall I run? the Throng draws nigh, / The Ball now Skims the Street, now soars on high.”

A decade later, Swiss travel writer César-François de Saussure recalled “a score of rascals in the streets kicking at a ball” who’d “knock you down without the slightest compunction; on the contrary, they will roar with laughter”.

Meanwhile, football was also played on the city’s fields and commons, and in public schools like Eton, Harrow and Charterhouse.

From the mid-1800s, enthusiasts began to organise themselves into the city’s first football clubs. And in 1863, the Football Association (FA) was founded. They drafted the first set of rules and regulations for the game, establishing modern football as we know it.