London’s iconic red telephone boxes

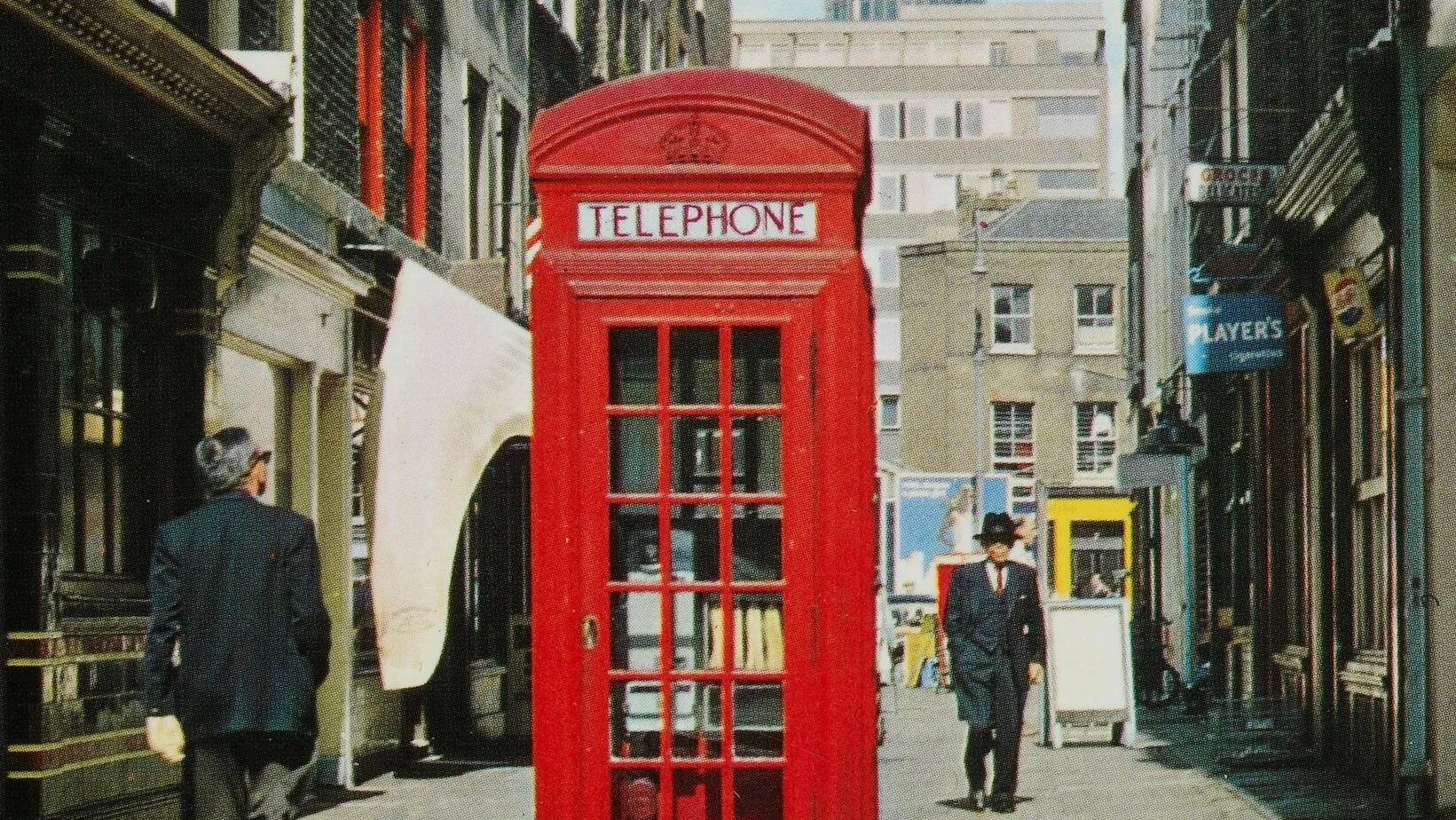

The red telephone box has become a charming, much-loved symbol of both London and Britain. Most no longer work, but you can still find them around the capital, where they remain a popular part of the city’s heritage.

Across London

Since 1926

Pick up, the future’s calling

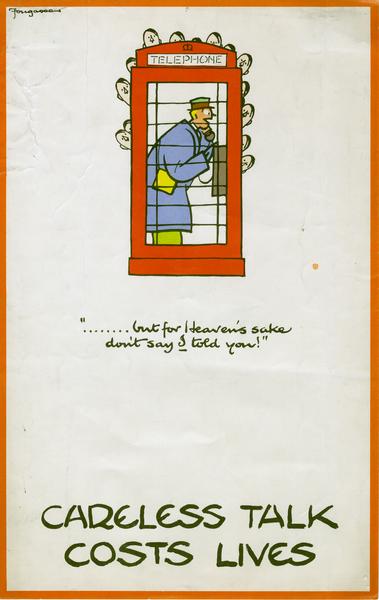

Phones first arrived in Britain in the 1870s. From 1884, telephone companies were allowed to install ‘public call offices’. These small booths, known as ‘silence cabinets’, appeared in shops, train stations and hotels. For the first time, Londoners could use phones to communicate while they were out and about. Outdoor freestanding wooden booths followed in 1912. They might not have offered the flexibility of mobile phones, but kiosks and call offices still opened up new possibilities.

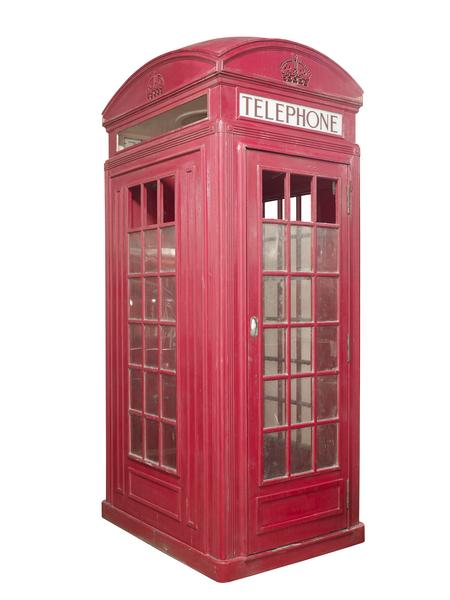

Giles Gilbert Scott and the K2

In 1924, a design by architect Giles Gilbert Scott won the competition to provide the General Post Office (GPO) with a standardised telephone kiosk. Scott’s domed cast-iron box was named the K2, short for Kiosk Number 2. He wanted them to be silver on the outside. But the GPO chose its trademark red instead, helping them stand out on the street. Almost all of the K2s were installed in London.

Blue police boxes

The Metropolitan Police had their own blue version between the 1930s and 1970s. They were used by the public to call for help, and by officers to contact their station, shelter inside, or temporarily detain someone. You can still see a replica outside Earls Court tube station. The boxes remain famous thanks to the long-running television series Doctor Who. Since the first episode in 1963, the Doctor’s time machine, the TARDIS, has disguised itself as a blue police box.

The Vermillion Giant

The GPO updated Scott’s design in 1925, creating the K4. It was known as the ‘Vermillion Giant’, and was meant to act like a mini post office. Each K4 had its own post box and stamp vending machine. Ultimately, it was too big, too expensive and the vending machine too noisy. Only 50 were made, and none were installed after 1935.

The Jubilee box

Scott updated his design for King George V’s Silver Jubilee in 1935. The result was the K6, the most famous model. Smaller, lighter, cheaper to make and easier to transport than the K2, there were over 20,000 K6s in cities, towns and villages across Britain by 1940. Some people in rural areas disliked the invasion of red – one critic called it “an evil deed in a good world”. But overall, they were incredibly popular, with 60,000 installed in total.

Promoting the network

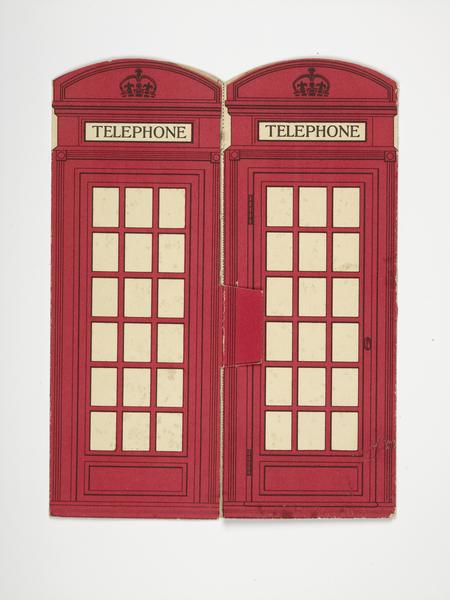

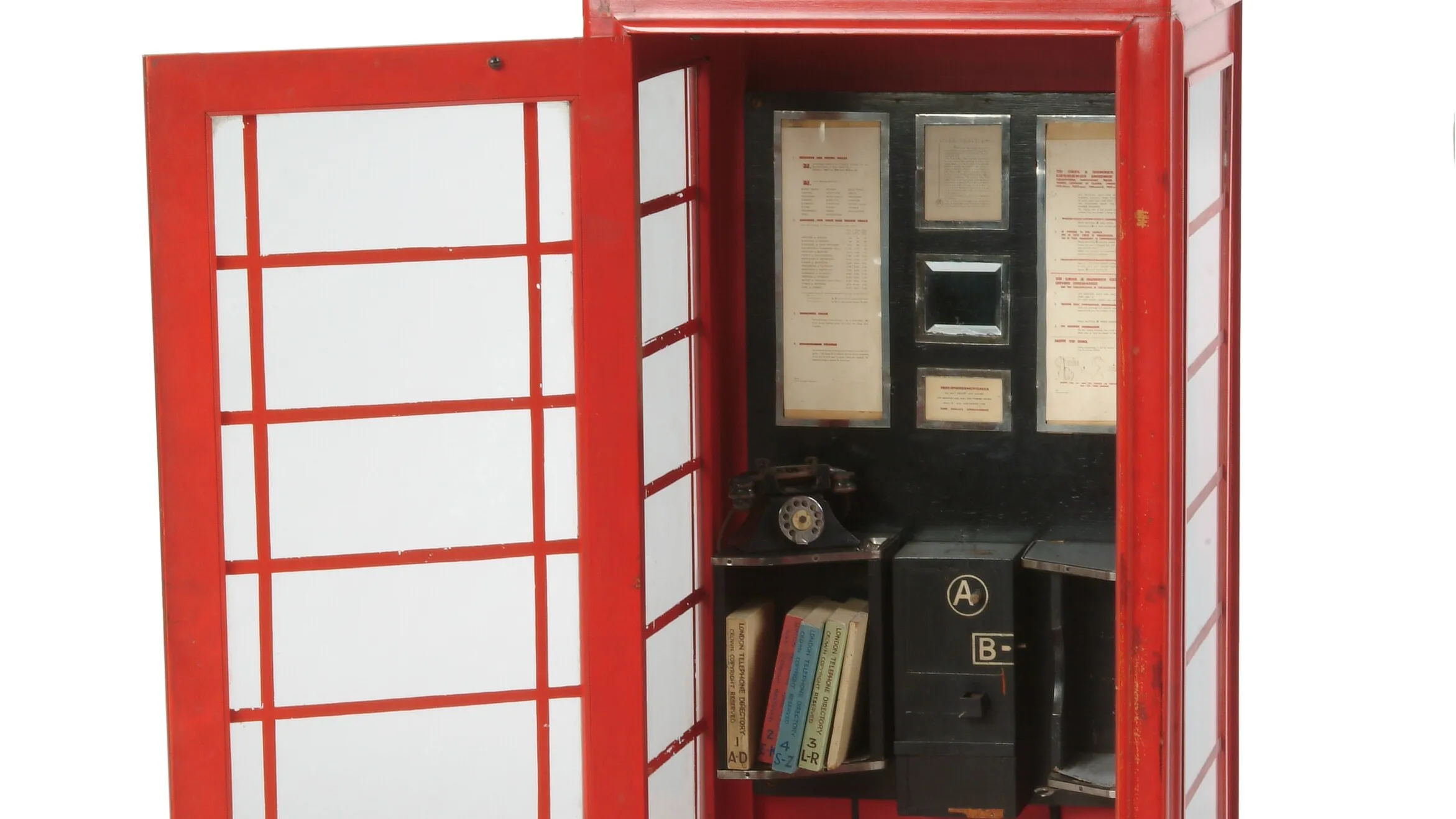

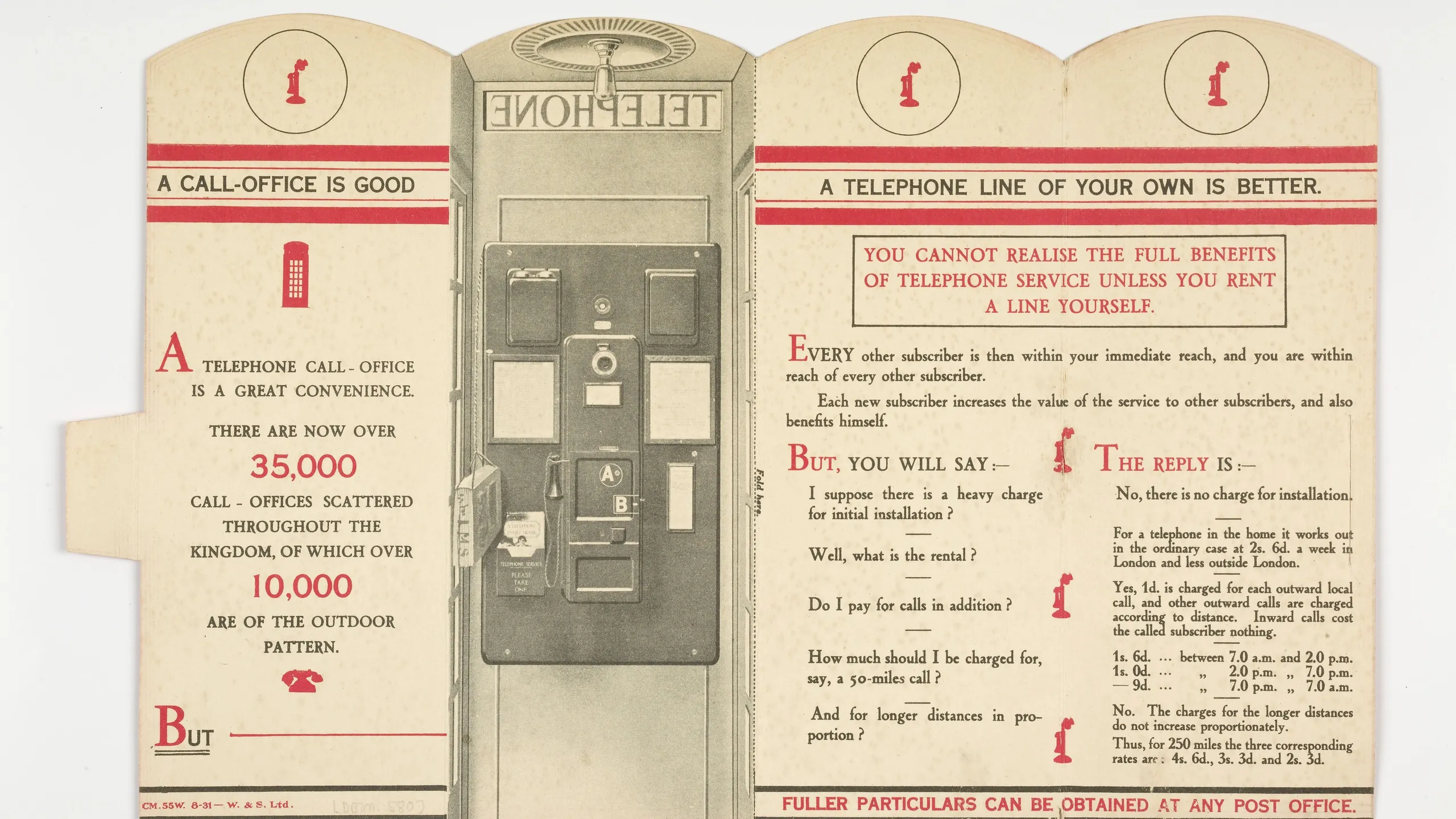

This leaflet from 1931 is shaped like a telephone box. The red exterior is shown on the reverse, so its four sides can be folded to make a 3D kiosk. The inside of the leaflet, shown here, advertises the network of public call offices and the added advantages of having a private telephone line. There’s also an illustration of the interior of a telephone box from the time.

Hanging up on the iconic red design

British Telecom (BT) took over the phone network in 1981, and introduced a radical update – the KX series. The KX was the first stainless steel kiosk to be rolled out nationally and the final death blow to the cast iron telephone box. BT also proposed ripping out all of the historic red telephone boxes. In response, the 20th Century Society launched a campaign to save them. Several thousand were listed, protecting them against removal.

Thinking inside the box

With phone boxes barely used nowadays, the technology might seem archaic to younger generations. Users paid for their calls by inserting coins. Or, if they didn’t have the funds, they could reverse the charges to the person they were calling. From the 1980s to the early 2000s, you could also use a phone card, loaded with a certain amount of call time. This one had 40 units.

Out of Order

A toppling row of red telephone boxes forms Out of Order, a sculpture by the artist David Mach from 1989. It can be found on Old London Road in Kingston upon Thames.

The fate of the red telephone box

Most of London’s surviving red telephone boxes are no longer hooked up for making calls. Instead, many have been adopted by local communities as makeshift libraries and galleries, or handy places to store emergency defibrillators. And, as a quintessentially British sight, they’re always a magnet for tourists wanting a souvenir snap. Where boxes have been replaced, new facilities have sometimes followed, offering free charging and WiFi.