Hop-picking: Londoners’ working holiday

Every year until the 1960s, as summer drew to a close, thousands of east and south-east Londoners flocked to Kent to help with the hop harvest. It was paid work, but the long days spent together in the fields still felt like a holiday from city life. Generations of the same families returned to farms years after year, decade after decade, until the invention of hop-picking machines brought the tradition to an end.

London Bridge & Kent

Until 1960s

Hop-picking goes back centuries

Beer made with hops was being brewed in England by the 1500s. London’s growing population, desperate to escape the overcrowded city, provided seasonal workers for the harvest. Before the 20th century, the hop-pickers’ working conditions were poor and employment wasn’t guaranteed. In 1755, the London Evening Post reported “one hundred poor persons of both sexes have died in barns and outhouses in Kent, for mere want of the necessaries of life, being part of the many hundreds that went from London expecting employment at picking of hops.”

Life on the farm

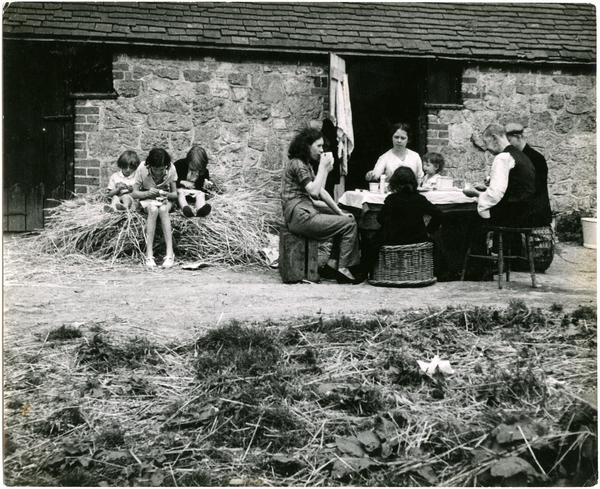

In the 1930s, tens of thousands of Londoners still went hop-picking every August or September, staying in farm huts for weeks. Accommodation had improved, but it was definitely basic. Toilets were usually a hole in the ground. Meals were cooked on fires in the open air. But Londoners went to great lengths to make it comfortable, journeying down a week early to prepare their hut. For many, this was the only time away from the city they could afford, and they were determined to enjoy it.

The journey

Londoners travelled by train, car, bike or horse and cart. Many hop-pickers set off from London Bridge station, heading to Paddock Wood, Yalding and other stations in Kent. Cheaper rail services were run especially for the hopping season. Loading up handcarts or prams, families brought pots and pans, bedding, curtains, food and clothes.

What are hops?

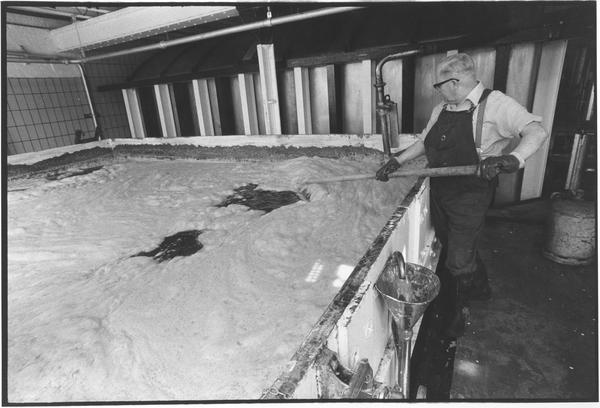

Hops are the ingredient that adds bitterness to beer. Farmers guide the plants up tall poles linked together with string. At harvest time, it was the pickers’ job to pull down its long stems and remove the flowers, steadily filling canvas bins. Men wore stilts to pull down the tallest vines. After picking, the hops were measured into large sacks called ‘pokes’, which were then dried in oast houses.

Waiting for the day

Londoners were invited back by the same farmers year after year, building relationships with other pickers that spanned decades. A 1900 report in Reynolds’s Newspaper described families “making for the fields with their letters of employment carefully folded… in their pockets”. Families looked forward to the day the letter came from the farmer – the signal that their summer adventure with friends and relatives was about to begin.

Whole families came

Hop-picking was an annual tradition involving every generation. Grandparents, cousins, aunts and kids all went ‘hopping’. The work was manual but easy to learn, so children could join in with the picking. While women and children set up their home away from home for the season, men with jobs in the city would join their families at the weekend.

Field days

Though the work could be hard, families made the most of their summer break from their daily routines. The evenings were filled with singing, dancing and games. Vendors sold food in the fields and pickers drank at nearby pubs. On Sundays there were open-air church services. There was a sense of freedom and togetherness. Romance was never far away, often between Londoners and locals.

The end of hop-picking

Hop-picking machines were introduced in the 1930s and gradually adopted over the following decades. By the 1960s, far fewer workers were needed to bring in the harvest. The sun had finally gone down on those blissful summer days.