The Gin Craze: Ruin of 1700s London

In the Gin Craze of the 1700s, Londoners hooked on cheap gin were driven to commit crime and sell their possessions to buy one more drink. The death rate rose and gin-drinking became a social crisis, leading to new laws to control it.

St Giles, Camden

1700–1750

Drinking to destruction

In the first half of the 18th century, a surge in the availability and popularity of cheap gin caused a dramatic rise in dangerous drinking among poor Londoners.

Addiction had a terrible effect on people’s health. It also strained society, causing spikes in drunkenness and crime, and generally worsening the quality of life in London’s poorest areas.

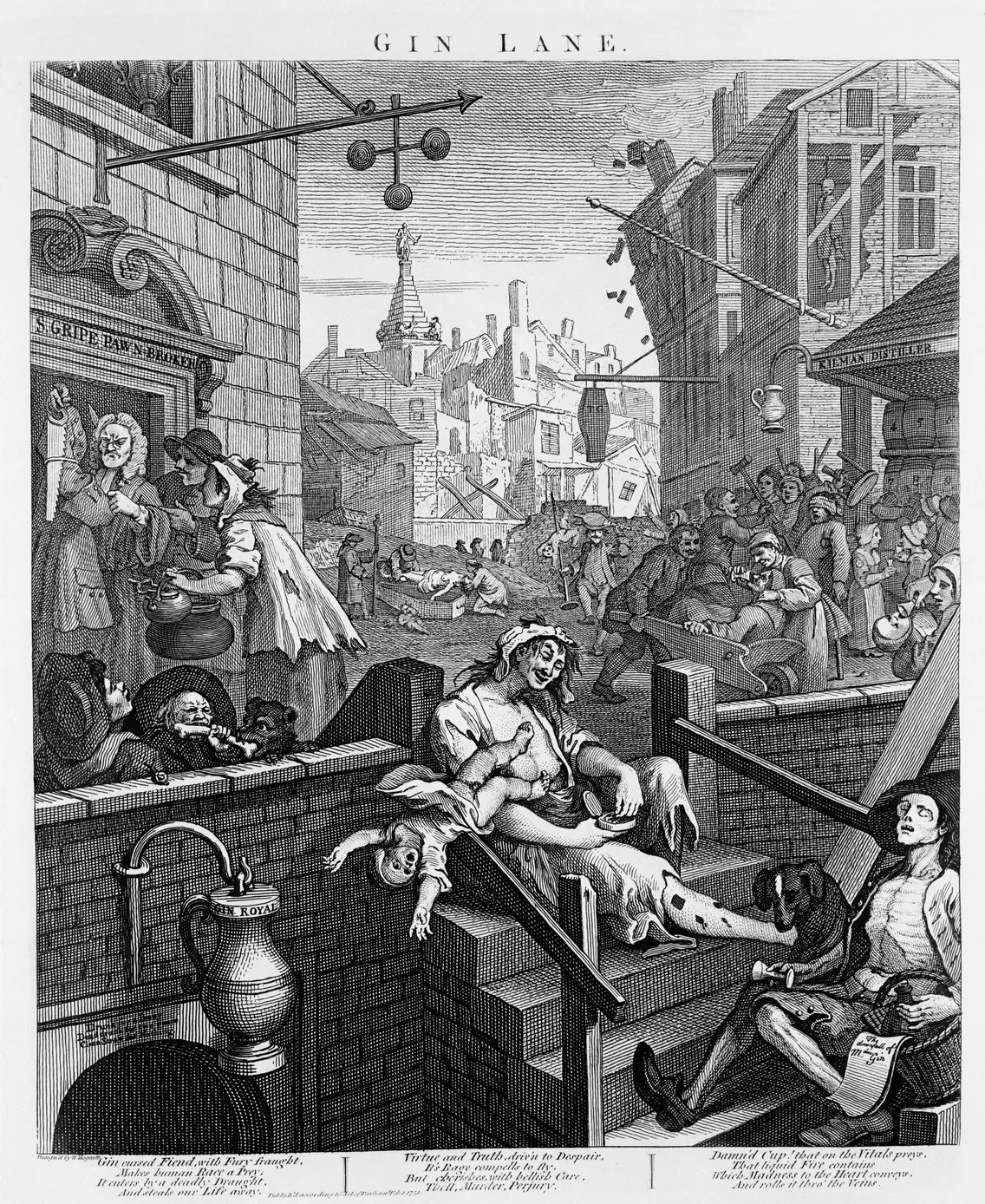

Gin-drinking caused a moral panic. To make the case for government action, the artist William Hogarth produced a hellish image of gin's effects, his famous Gin Lane.

Parliament did respond. A series of laws pushed up the price of gin and limited the numbers distilling and selling it.

The drinking habits of working-class people continued to be scrutinised. And many features of the conversation around the Gin Craze are still seen today. Reports of various drug epidemics – heroin, crack cocaine, spice, fentanyl – have all made headlines in modern times.

Beer was the most common drink among poor Londoners before the 18th century.

How did gin become such a problem?

The drinking of alcoholic spirits wasn’t widespread before the 18th century. Beer was the most common alcoholic drink among poor people. It was rich people who first started drinking spirits.

But beer gradually became more expensive due to rising taxes. At the same time, taxes on spirits fell, making them cheaper.

In 1689, the government banned spirits imported from France, who it was at war with. Gin was promoted as an alternative to French brandy. And there were no regulations specifying who could make it.

Gin could be made cheaply in Britain from British corn. By the 1720s, London was the centre of the gin distilling trade, and Londoners consumed the majority of the gin made in the country.

It was more easily available than clean water and, crucially, affordable to all. Gin was drunk by men, women and children. In 1723, it was estimated that, on average, Londoners were drinking one pint (570 ml) of gin per week.

Gin shops were everywhere

Gin could be made and sold without a licence, so shops popped up all over the place.

St Giles, near Covent Garden, was a hotspot. It was a poor area in the 1700s, a tight jumble of alleyways and crumbling buildings. One in five houses was a gin shop. Many doubled as brothels.

There was no escape from temptation – you could buy gin from grocers, barbers, chandlers, market stalls and street-sellers.

“Drunk for a penny, Dead drunk for two pence”

A reported advert for gin

What problems were caused by gin addiction?

Crime and alcohol-related deaths increased. Those who were addicted to gin spent much of their money on drink, which forced them into desperate poverty. And when the money ran out, some sold anything they could to keep the alcohol flowing.

Chilling stories surfaced as anxieties about the situation grew. Commentators were especially concerned about how gin was affecting women and children. One woman, Judith Defour, was reported to have killed her baby to sell its clothes for a drink.

But some of the criticism of gin-drinking discriminated against poor people. It was said that they were being less productive, becoming unruly or getting a taste for luxury. Some of these worries reflected the fact that London was growing dramatically during this time.

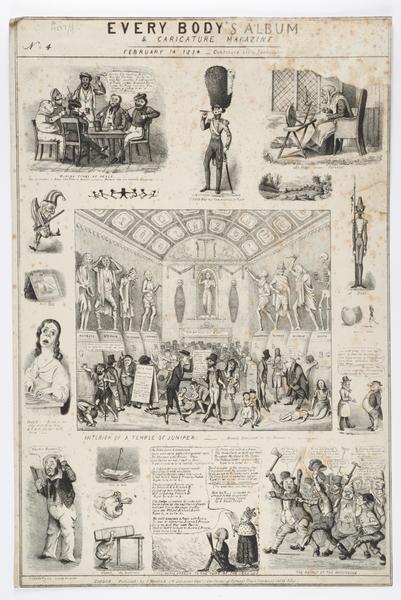

William Hogarth’s Gin Lane

One image has come to sum up the Gin Craze. It’s an engraving by the London-born artist William Hogarth titled Gin Lane.

The print was published in 1751 as part of a campaign against gin-drinking started by the novelist Henry Fielding.

The scene is set in St Giles. In the centre, a partly undressed mother with syphilis allows her baby to fall from her lap. Elsewhere, children and a baby drink. Bedraggled Londoners pawn their possessions. Others riot. One has hanged themself. Buildings in the background crumble and fall.

It’s a wild nightmare, not a picture of reality. But that’s what made it a powerful piece of propaganda.

A sign in the foreground, inspired by a real sign Hogarth had seen, reads:

“Drunk for a penny

Dead drunk for two pence

Clean straw for nothing”

Copies were sold for a shilling, much less than the usual price of engravings like these, making them more accessible to collectors.

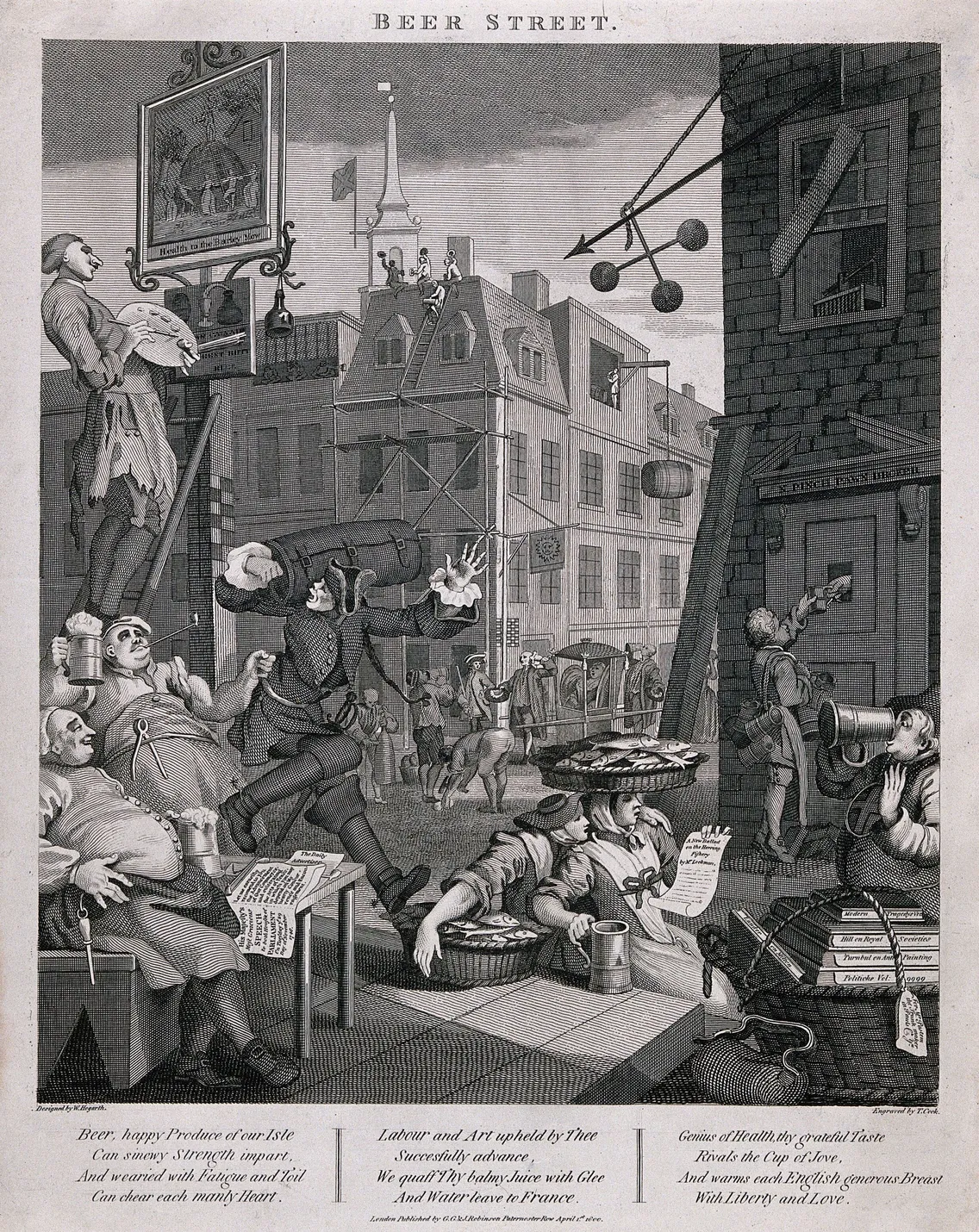

It was sold with another print, Beer Street, where Hogarth portrays a wealthy area of Westminster. Instead of chaos and tragedy, this is a thriving community powered by beer. In the text below the image, it begins:

“Beer, happy Produce of our Isle

Can sinewy strength impart”

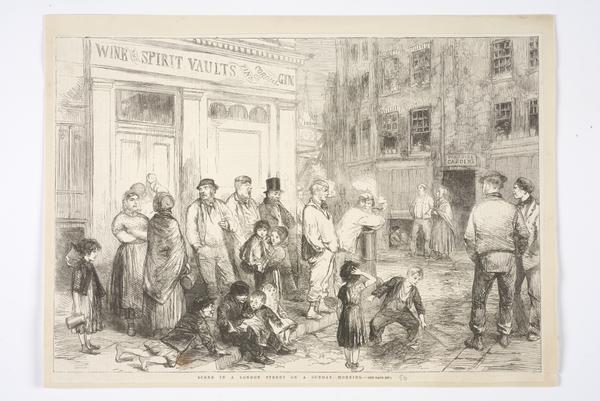

Thomas Rowlandson’s drawing of a gin shop from around 1808.

What did the government do about the Gin Craze?

The government introduced a series of laws in 1729, 1736 and 1743 which placed taxes on gin distillers. An annual licence for those wanting to make and sell gin was also introduced. The attempts to control drinking led to riots – people chanted “no gin, no king”.

The 1751 Gin Act was even stricter. Only those who paid rent and taxes could sell gin. And a system of progressively tougher punishments was introduced. Get caught selling gin illegally three times and you’d be transported to a prison camp in America or Australia.

The gin problem did improve. Fewer people were distilling and selling the spirit, so gin-drinking decreased. But this was also because corn, and therefore the price of gin, became more expensive.

Did gin-drinking stop being a problem?

Gin continued to be a popular drink among working-class people. By the end of the 18th century, it was estimated that one in every eight deaths in adults over the age of 20 was caused by drinking spirits.

In the 19th century, concerns over alcohol consumption spawned the influential temperance movement, which campaigned against using and selling alcohol, and promoted total abstinence.

Victorian London also witnessed the arrival of opulent gas-lit ‘gin palaces’. Like the Gin Craze of the previous century, these rivals to the traditional pub inspired panic about their effects on working-class people.