Chimney sweeps’ soot-stained past

Chimney sweeps once provided an essential service to every London home. Until 1875, their trade relied on young boys climbing into danger.

Across London

Since 1500s

What does a chimney sweep do?

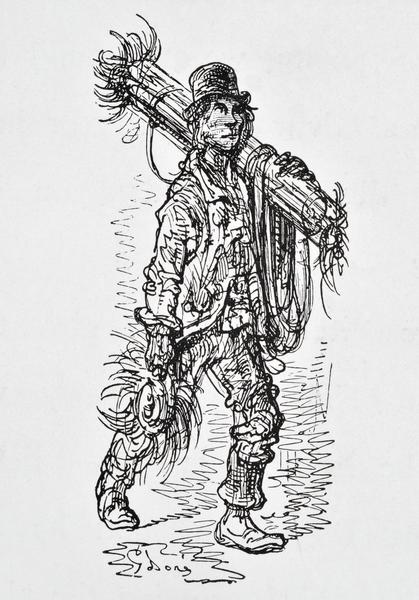

Sweeps clear out the flammable soot which builds up in chimneys, reducing the risk of fire. They've been around in Britain since at least the 1500s, but their trade expanded rapidly during the industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries. As more coal was mined, more Londoners used this dirtier fuel to heat their homes instead of wood. Chimney sweeping became a lucrative trade, and businesses capitalised by using child labour.

‘Climbing boys’ were used until the 19th century

Master sweeps kept children as apprentices because they were small enough to squeeze inside narrow chimneys. Long brushes could only do so much. For a thorough clean, the ‘climbing boys’ were sent in to scrape away soot. Climbing was dangerous. Sweeps could be burned, get trapped or fall. And the soot could cause cancer. Many sweeps’ apprentices died as a result.

A harsh life

Master sweeps took apprentices from poor families, promising to provide food, clothing and housing. But master sweeps had a reputation for cruelty. Although officially illegal, some took children as young as five. The apprentices were sometimes starved to stunt their growth. Despite this, people’s need for sweeps often outweighed concerns for the children’s working conditions.

Were women and girls chimney sweeps?

Master sweeps were typically men. But women ran chimney sweeping businesses too, often taking over the family firm after the death of a husband or father. In the 18th century, Jeane Tempell ran a respected service in Holborn. Mrs Bridger, who had a business on Regent Street, was known for her cruelty to her apprentices. It was rare but not unknown for girls to be used for climbing chimneys.

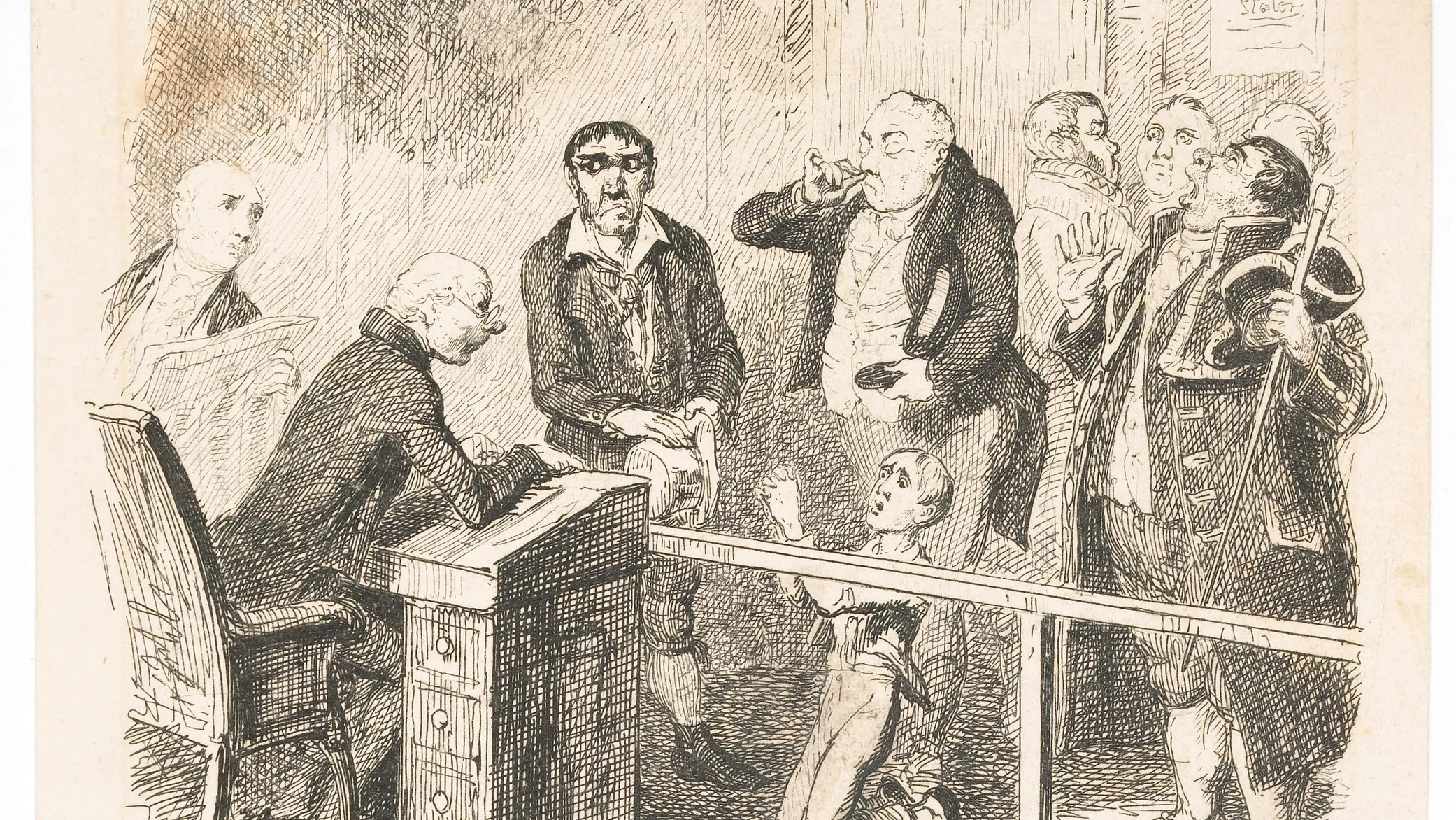

Oliver Twist

The novelist Charles Dickens addressed the mistreatment of young sweeps in Oliver Twist, published in 1838. The main character is an orphan living in a workhouse. A master sweep, Mr Gamfield, bids to take him as an apprentice. In the scene shown here, Twist begs not to go with Gamfield, whose “villainous” appearance is said to be a “stamped receipt for cruelty”. One character describes chimney sweeping as “a nasty trade”.

When were child chimney sweeps banned?

As early as 1788, a law was passed to regulate the employment of children as sweeps. But it wasn’t enforced. Children continued working and dying in chimneys. In 1834, 1840 and 1865, more laws tried and failed to end the practice. The last climbing boy to die from his work was George Brewster in 1875. His death led to the 1875 Chimney Sweepers’ Act, which forced sweeps to be licensed, and finally required the police to enforce previous rules.

Little Conduit

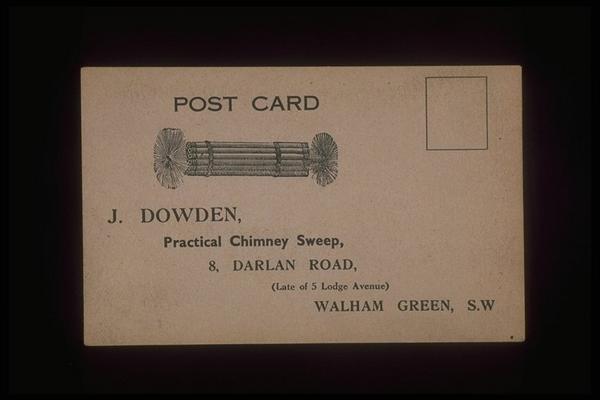

In central London, sweeps traditionally gathered to socialise and seek work at Little Conduit, a water collection point on Cheapside. It’s the setting for this 18th-century painting showing three young sweeps. More established chimney sweeps had regular contracts for homes or businesses, and advertised their services with trade cards.

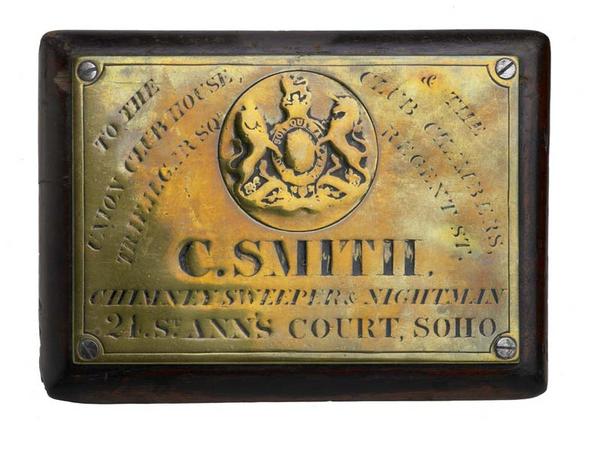

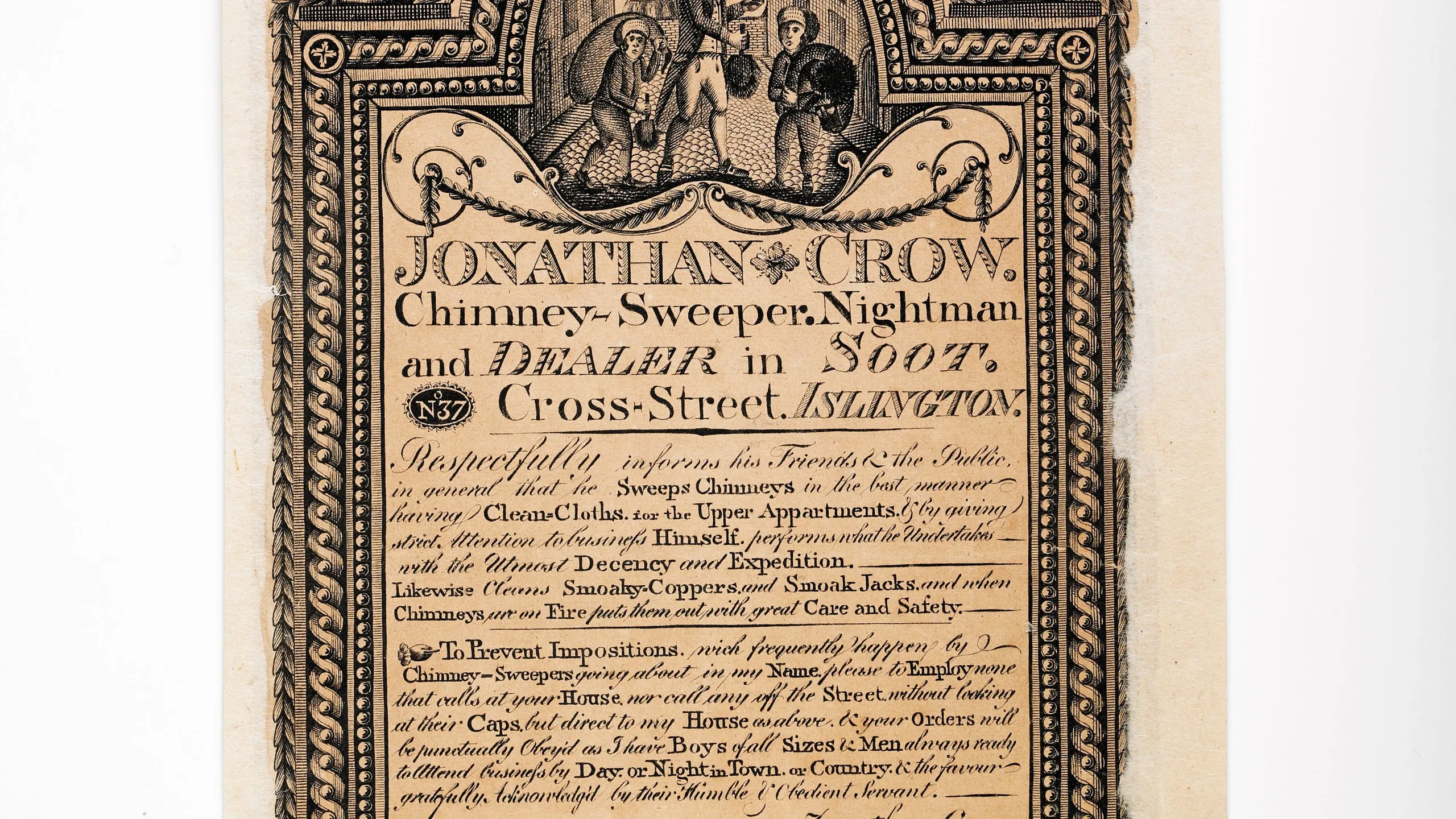

“Chimney sweeper, nightman and dealer in soot”

Chimney sweeps started work at dawn. They often paired their trade with work as ‘nightmen’, emptying people’s toilets when the skies were dark and the streets were quiet. The trade card pictured here lists both services. It also mentions that the sweep was a “dealer in soot”. Soot removed from chimneys was sold as fertiliser to farmers and gardeners.

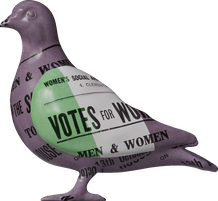

Sweeps were part of London’s culture

For the city’s first of May celebrations, also known as ‘sweeps’ day’, apprentices were given the day off. Sweeps paraded in the street alongside milkmaids and a costumed Jack-in-the-Green. Some apprentices had another moment of rest at an annual dinner, paid for by their masters, at White Conduit House in Islington. Chimney sweeps became a lucky charm, too, invited to weddings to bring the couple good fortune.

A sweeps' arm badge

As well as the paintings and prints in our collection showing chimney sweeps, we also have this arm badge. It was sewn onto the uniform of a sweep working for C Smith and Company, based at St Ann's Court, Soho.

Chimney sweeps dwindled in the 20th century

This sweep was photographed in 1968. The trade flourished until the second half of the 20th century, when homes and businesses switched from burning coal to using gas and electricity. This transition was partly caused by government action on air pollution, with the 1956 Clean Air Act creating smoke-free areas in London. There are still chimney sweeps working today, albeit in far smaller numbers.

Chim Chim Cher-ee

In complete contrast to the history of Victorian child exploitation, the 1964 Disney film Mary Poppins seared a more cheerful image of chimney sweeps into popular culture. Dancing sweeps bound across London rooftops in a jolly musical sequence starring Dick van Dyke, whose awful attempt at a Cockney accent has also left its mark. The lyrics tell us “a sweep is as lucky as luck can be”.