Agnes Marshall: The Victorian queen of ice cream

This east Londoner ran a leading cookery school, wrote four recipe books, developed pioneering kitchen equipment and led the way in ice cream innovation. So why isn’t she a household name?

East London

1852–1905

The 19th-century food influencer and innovator

Agnes Marshall was a woman of many talents: cook, teacher, businessperson, food writer, recipe developer, inventor. She was the 19th-century equivalent of a celebrity chef, marketing her personal brand long before the modern ‘influencer’ became a thing.

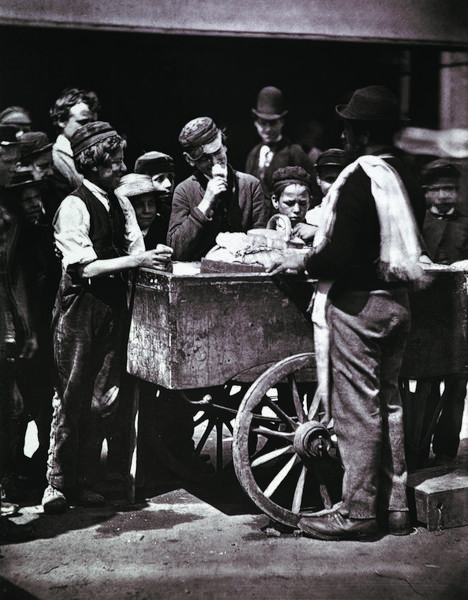

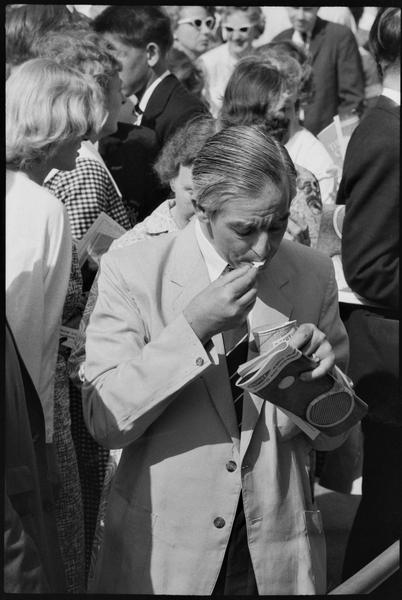

Marshall was best known at the time as an authority on ‘ices’. Victorian Britons went mad for frozen novelties like ice cream and sorbets. Where working class people bought small-scoop ‘penny licks’ served in glasses from street sellers, middle- and upper-class people looked to Marshall for their homemade dessert inspiration.

Her recipe books, branded kitchen equipment and recipe innovations pushed the art of ice cream forward in Londoners’ homes. She might even have invented the ice cream cone.

Where and when was Agnes Marshall born?

Most sources on Marshall’s life will tell you she was born in Walthamstow in 1855. But recent research suggests she’s actually three years older and was born in Haggerston, Hackney. Her parents were unmarried – something that was widely seen as shameful in Victorian times. Marshall was possibly raised by her grandmother.

We don’t know much about her early life, or how she started cooking. In the preface to her second book, she writes how her recipes were “the result of practical training and lessons, throughout several years, from leading English and Continental authorities”. We don’t have much evidence for this beyond her word.

Marshall set up her own cookery school and equipment business

Marshall was first and foremost a businessperson. In 1883, she and her husband, Alfred, set up the Marshall’s School of Cookery on Mortimer Street, just above Oxford Street.

It was only one of two major cookery schools in the city, competing with the The National Training School of Cookery in South Kensington. London society newspaper The Queen said “Mrs A. B. Marshall must be doing a grand work, for pupils seem to literally pass through her hands by thousands”.

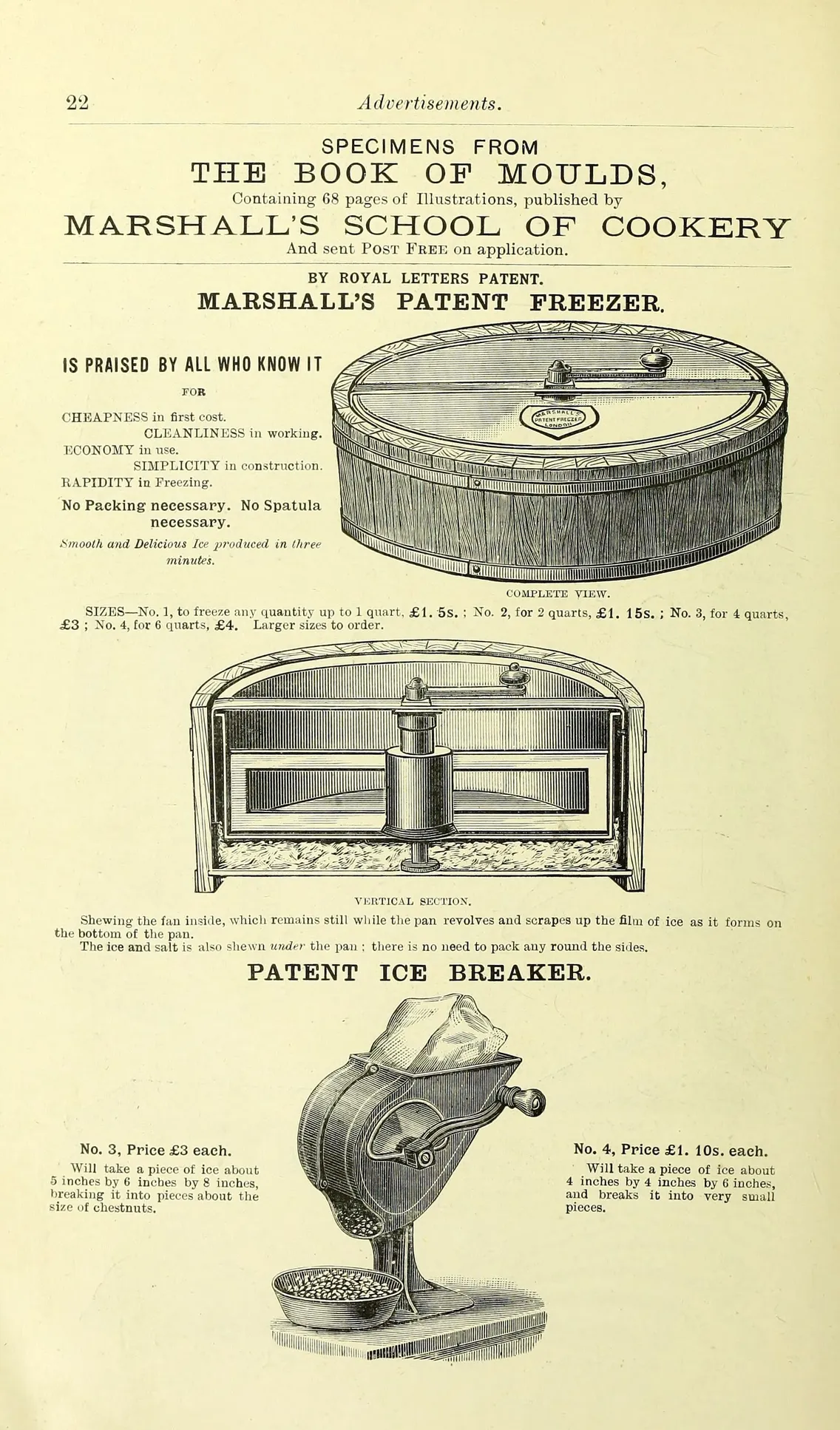

The Marshalls also made and sold cooking equipment under the family name, which were stocked by department stores like Harrods. Their inventions included the Marshall’s Patent Freezer. This was a hand-cranked ice cream machine with a wide base that promised “smooth and delicious Ice produced in 3 minutes” – faster than previous iterations of ice cream machines.

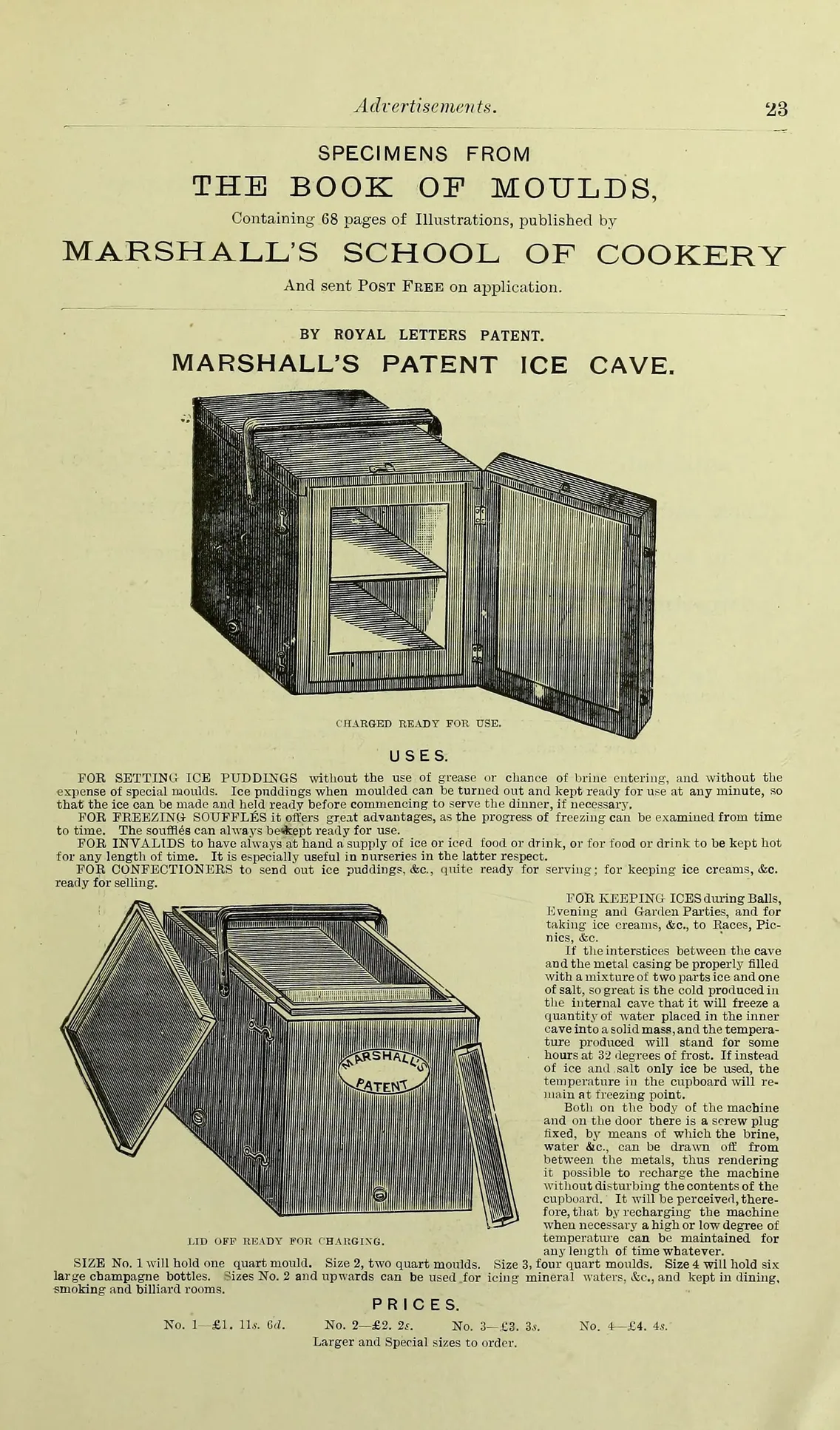

There was also the Marshall’s Patent Ice Cave, an insulated box that functioned as an early refrigerator and could keep your sweet treats cool.

At a time when many women’s lives were constrained to the home, Marshall had a very public profile and thrived in the world of business. Thanks to a law passed in 1882, she could buy and control property without her husband’s consent.

Her books on ice cream were a hit

Marshall published her first cookbook, The Book of Ices, in 1885. Much of it is dedicated to ‘cream ices’, but she’s also got recipes for ‘water ices’ (sweetened, flavoured water), sorbets (like water ices, but with alcohol) and frozen souffles. You’ll find a real rainbow of flavours inside – classics like strawberry or chocolate, curveballs like cucumber or white wine.

Her writing is clear, well-researched and full of tips. Too much sugar prevents ice from freezing, she tells us, and too little makes it hard and rocky.

Yes, Marshall wasn’t the first to give us recipes for ice creams in Britain. That award goes to confectioner Mary Eales and her book Mrs. Mary Eales’s Receipts, published in London in 1718. But Marshall popularised ice creams among middle- and upper-class people looking to impress dinner guests at home, earning her the nickname ‘Queen of Ices’.

She wrote three more successful books, all published by Marshall’s School of Cookery. The 1888 book Mrs. A.B. Marshall’s Cookery Book has dinner recipes spread over 400 pages. Unlike famous Victorian food writers like Isabella Beeton, whose hugely popular Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management adapted existing recipes, Marshall assures us she’s made and tested every recipe herself.

“some of the prettiest dishes it is possible to send to the table”

Agnes Marshall, 1885

The Marshall’s brand

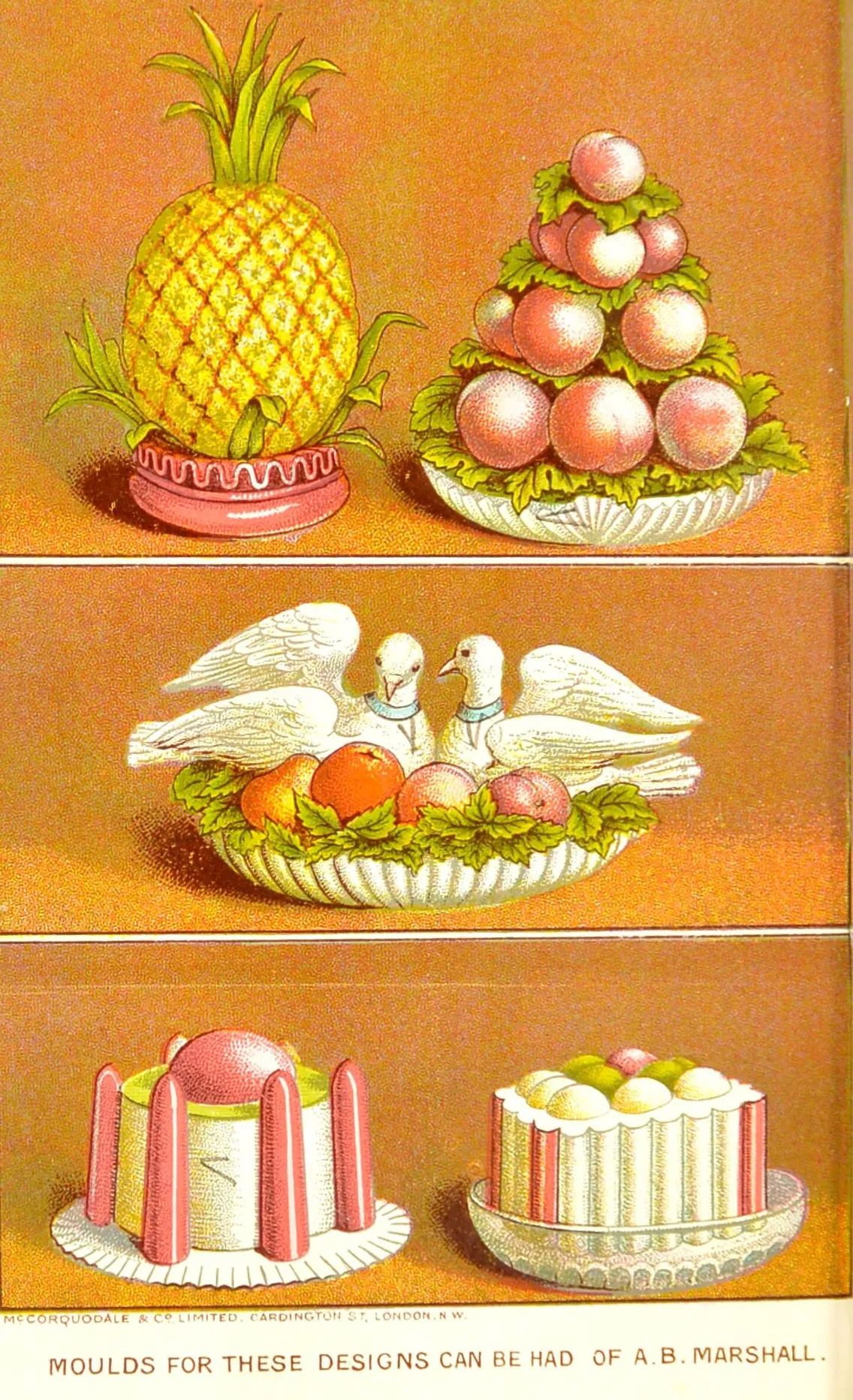

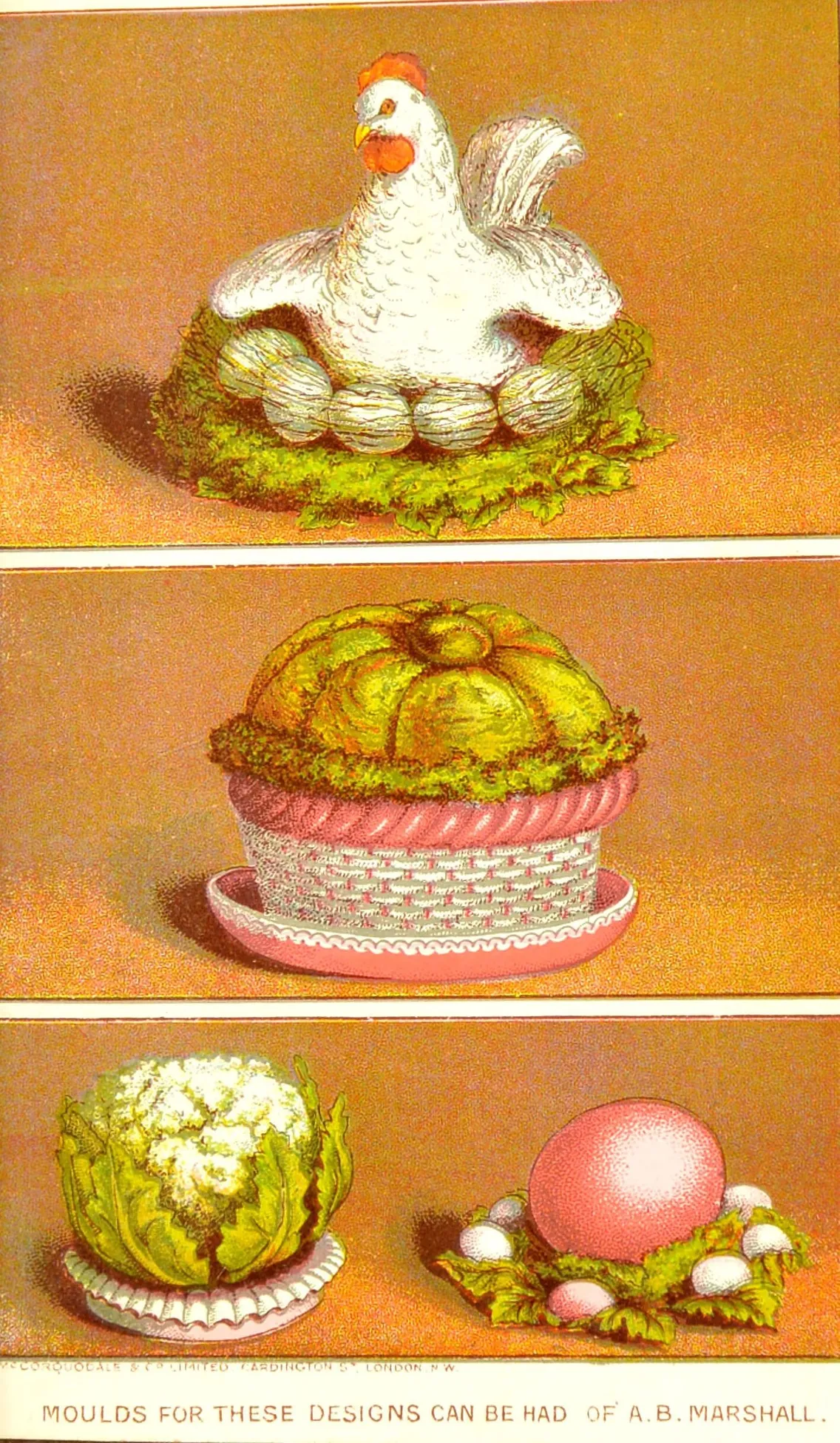

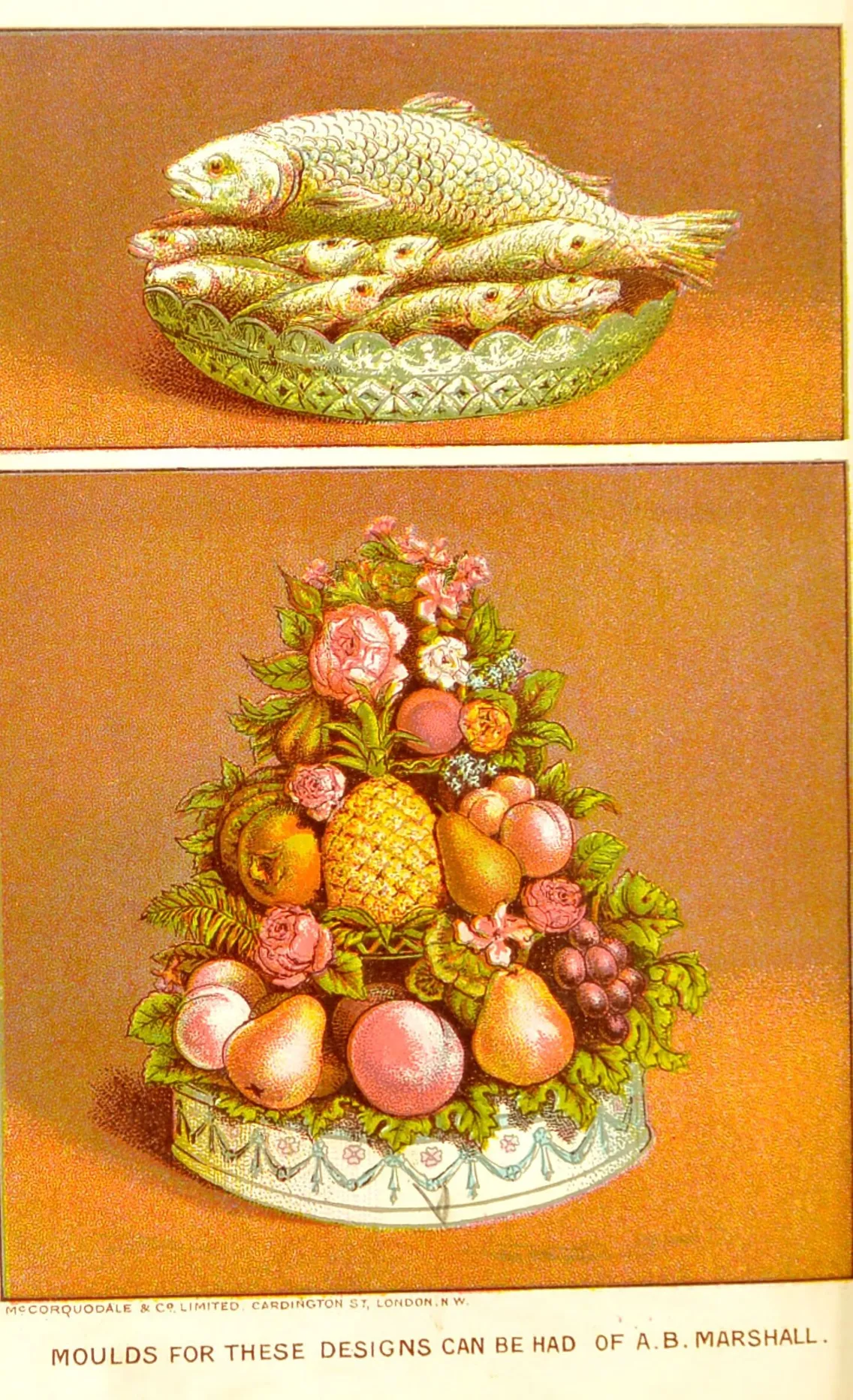

Marshall was a master of cross-selling. Her books are stuffed full of advertisements for the Marshall’s brand, including some pretty extravagant moulds sold from the School of Cookery. Imagine the thrill of having your dessert served in the shape of a beehive, asparagus, fish or swan.

The moulds, Marshall writes, “afford to the cook the opportunity of making some of the prettiest dishes it is possible to send to the table”. Just 100 years earlier, these extravagant moulded desserts would have been the exclusive joys of the rich and royal.

What if her desserts seemed a little too complicated? “Those who wish to be proficient,” she suggests, “can save themselves a great amount of time, trouble and anxiety… by attending Marshall's School of Cookey on any day arranged for ‘Ices’.”

An innovator who brought science to cookery?

In her 1888 book, Marshall includes a recipe for “cornets with cream”. These were cones made from baked almonds that could be shaped and filled “with any cream or water ice”. It’s one of the first references to ice cream being served in an edible cone.

“one of the greatest culinary pioneers this country has ever seen”

Heston Blumenthal

This would have been a novel concept to Victorian Londoners. Many ate cheap ice creams served in small glass containers called penny licks, which looked a bit like a filled-in shot glass. You’d lick the glass clean and return it to the seller, who’d then give it a quick rinse with water, ready to serve to the next customer.

A food hygiene campaigner like Marshall might not have been such a big fan of penny licks. They were eventually banned in 1926 for spreading diseases like tuberculosis.

In 1901, Marshall also suggested using “liquid air”, probably liquid nitrogen, to freeze ice cream long before the idea took off in the culinary world. Around 100 years later, west London-born scientist-chef Heston Blumenthal popularised liquid nitrogen in his fine dining cookery. Even he credits Marshall as “one of the greatest culinary pioneers this country has ever seen”.

Marshall’s importance has long been overlooked

Marshall died in 1905 from complications after falling from a horse. She was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium, Barnet, and her ashes were buried at Paines Lane Cemetery, Harrow.

The rights to her books were sold to the publishers of Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management. Her kitchen equipment business was sold. And her husband remarried – to one of her former secretaries.

Marshall was famous during her lifetime. Her cookery school didn’t close until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Her weekly culinary magazine The Table, which she started in 1886, was in print until then, too.

But her name fades into obscurity after her death. It’s only recently that food historians and enthusiasts alike have started to shine a light on one of Britain’s first celebrity chefs.