St Benet Sherehog churchyard

The church and graveyard of St Benet Sherehog, otherwise known as ‘No 1 Poultry’, was excavated between 1994 and 1996.

The construction of the church most likely dates to the late 11th century and was home to one of the smallest parishes in the City of London until its destruction during the Great Fire of London in 1666.

The once affluent parish appears to have declined during the 16th and 17th centuries and was not rebuilt following the fire. Thereafter, the land was used as a burial site for both the St Benet and St Stephen Walbrook parishes until it was closed by an act of Parliament in 1853.

Of the 274 individuals recovered during excavation by the Museum of London Archaeology Services (MoLAS), 39 were medieval and 235 post-medieval. Of the latter, 231 individuals were retained for analysis and are believed to date primarily from the 16th and 17th centuries. All individuals were buried in coffins, aligned roughly east to west and a number of copper alloy shroud pins were recovered during the excavation. Parish records indicate that the burial ground was shared by both the wealthy and poor.

Methodology

Dental measurements were not recorded for subadults for this site.

Preservation

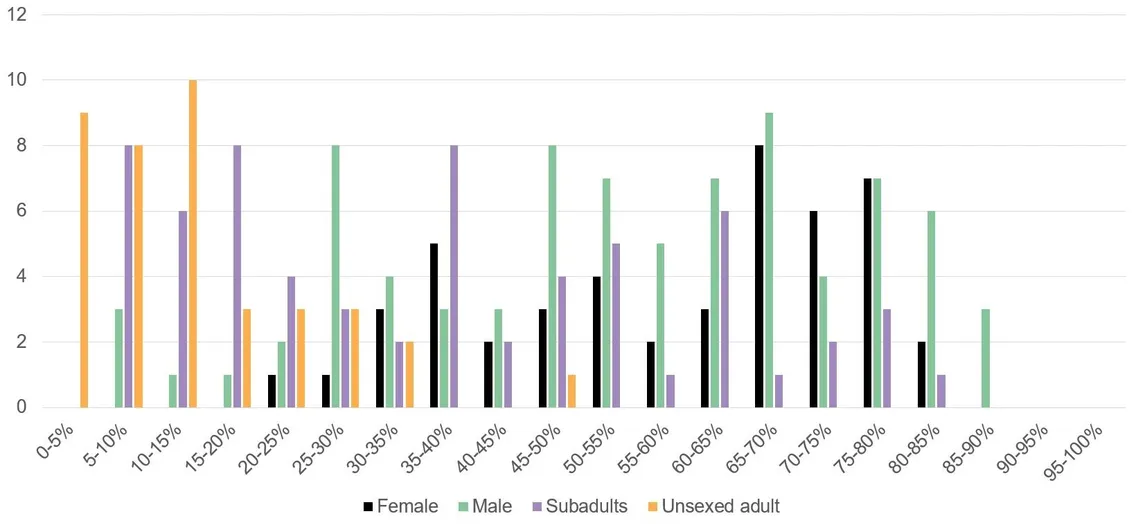

Only 42% of individuals excavated were more than 50% complete. However, the majority of bone recovered was well-preserved (Table 1). Sub-adults were perhaps unsurprisingly the least complete, while 24% of adults could not be sexed due to poor preservation (Fig 1).

| Preservation | N= | % |

|---|---|---|

Good |

172 |

74.5 |

Medium |

55 |

23.8 |

Poor |

4 |

1.7 |

Figure 1: Skeletal completeness (N=231)

Demography

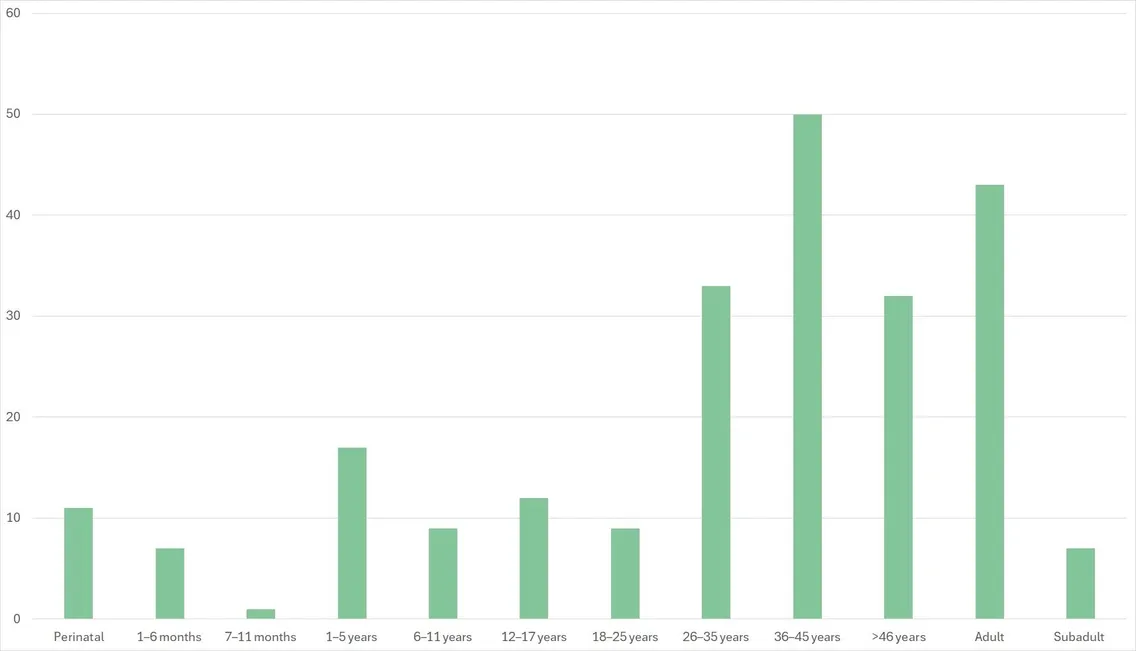

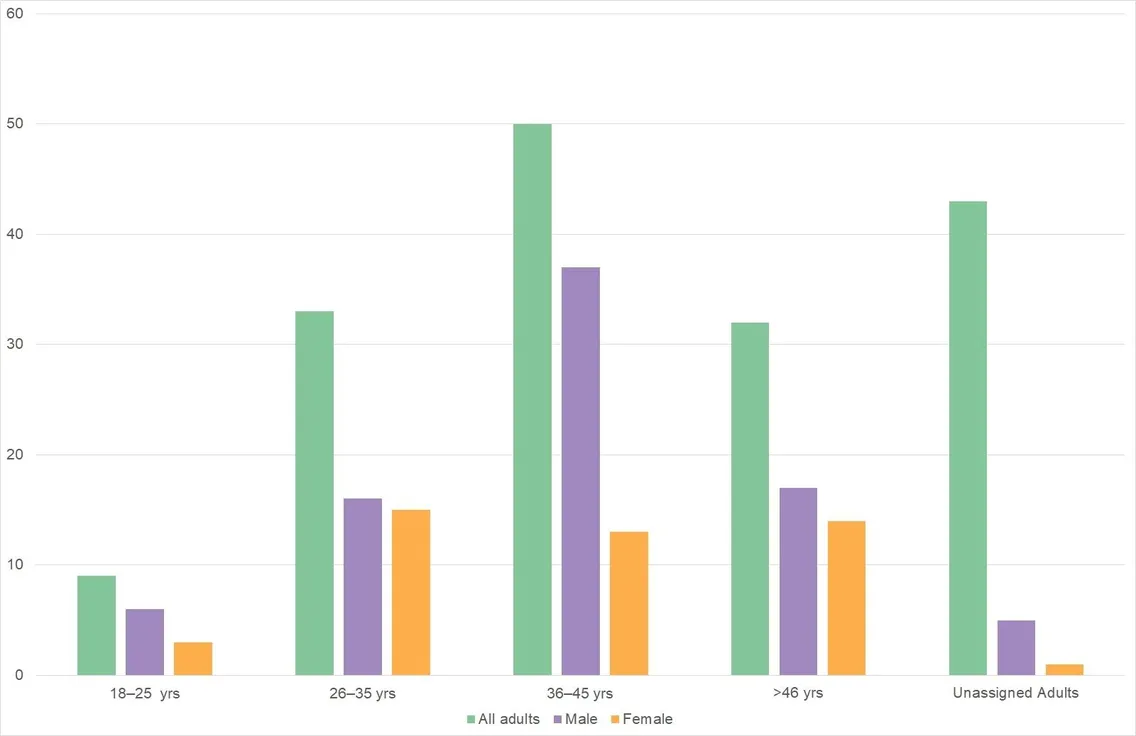

The 231 individuals from the post-medieval cemetery of St Benet Sherehog were included in this analysis. Of them, 167 were adults, including 81 (48.5%) males, 46 (27.5%) females and 40 (24%) unsexed individuals. Of all adults, the single largest group was the 36–45-year age category, accounting for 30% of the adult population.

Analysis of the age/sex distribution indicated that this group also had a much higher male to female ratio that any other group, with approximately 2.8 males to every female.

A total of 64 sub-adults were recovered, accounting for 27.7% of the population. Of these, 11 (17.2%) were perinatal infants, while 17 (26.6%) deaths were attributed to children between the ages of 1 and 5.

Figure 2: Age distribution (N=231)

| Age | N= | % |

|---|---|---|

Perinatal |

11 |

4.8 |

1–6 months |

7 |

3.0 |

7–11 months |

1 |

0.4 |

1–5 years |

17 |

7.4 |

6–11 years |

9 |

3.9 |

12–17 years |

12 |

5.2 |

18–25 years |

9 |

3.9 |

26–35 years |

33 |

14.3 |

36–45 years |

50 |

21.6 |

>46 years |

32 |

13.9 |

Adult (>18 years) |

43 |

18.6 |

Subadult (<18 years) |

7 |

3.0 |

Six individuals of known age and sex were excavated, comprising two women and four men. Beyond the obvious biographical data little is known about them.

Figure 3: Adult male and female distribution (N=167)

| All adults | % | Male | % | Female | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18–25 years |

9 |

5.4 |

6 |

7.4 |

3 |

6.5 |

26–35 years |

33 |

19.8 |

16 |

19.8 |

15 |

32.6 |

36–45 years |

50 |

29.9 |

37 |

45.7 |

13 |

38.3 |

>46 years |

32 |

19.2 |

17 |

21.0 |

14 |

30.4 |

Unsexed Adults |

43 |

25.7 |

5 |

6.2 |

1 |

2.2 |

Total |

167 |

81 |

46 |

Stature

Stature estimation derived for individuals with complete femora indicated that the heights for both male and females were consistent with other British post-medieval populations.

| Sex | Avg_stat | SD | VAR | MIN | MAX | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Female |

160.2 |

3.3 |

11.2 |

155.7 |

165.2 |

9 |

Male |

169.4 |

6.3 |

39.2 |

158.8 |

177.1 |

12 |

Pathology

Trauma and infectious diseases were on the rise in this period, largely due to growing industry, urbanisation and subsequent overcrowding. These trends are visible among the St Benet Sherehog population. For instance, there is a high incidence of trauma throughout the adult population, often visible with secondary arthritic changes.

Infections were also well-represented with 20.3% of the population having some form of non-specific infection, in addition to several cases of tuberculosis and syphilis.

Metabolic diseases are characteristic of post-medieval populations and this is reflected here, with children having histiocytosis X, scurvy and rickets. The latter vitamin D deficiency was notably retained into adulthood due to the bowing of adult long bones, and several adults exhibited signs of osteoporosis.

Of further interest is an early craniotomy of a child approximately 7 years old and a number of adults with dental wear indicative of habitual pipe smoking.

Vertebral pathology

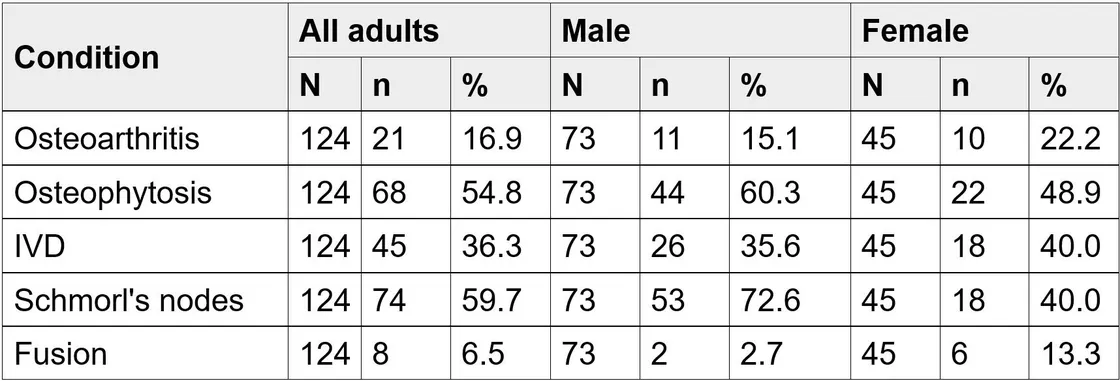

Crude distribution analysis of adult vertebral pathology indicated that women had higher rates of osteoarthritis, intervertebral disc disease (IVD) and fusion in the spine, with approximately 5% more females than males affected by each disease. Among males, 32.6% had more Schmorl’s nodes.

Table 5: Distribution of vertebral pathology by sex in adults with one or more vertebrae present

Dental pathology

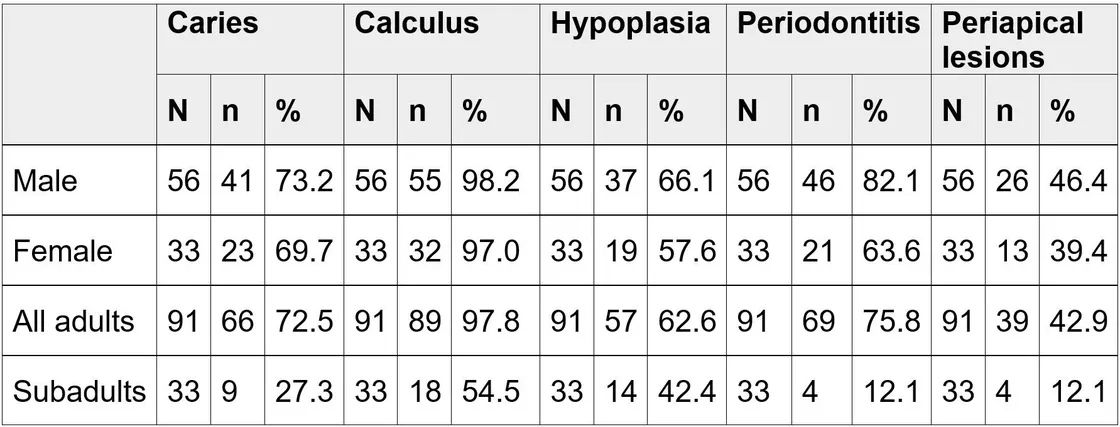

The dental pathology was generally representative of a post-medieval population. There was almost a 100% prevalence of calculus and approximately 70% of caries observable in the adult population, which can be linked to the increased circulation of refined sugar during this period.

There was a notably higher incidence of periodontitis among males by almost 20%. A high prevalence of enamel hypoplasia was visible throughout the site, which may be attributable to the growing number of diseases and environmental stressors affecting children through early development in the post medieval period.

Table 6: Distribution of dental pathology by sex in adults with one or more vertebrae present

Discussion

The St Benet Sherehog individuals represent a post-medieval urban population from within the City of London, during the 16th and 17th centuries. Large numbers of trauma, infectious disease and metabolic disorders are all representative of the post-medieval period.

Due to its large, stratified sample of middle status individuals, it is an excellent site for both original and comparative research. For example, it could be compared to affluent post medieval populations such as Chelsea Old Church or poor populations like Red Cross Way.

The large number of individuals with metabolic disorders lends itself to further study, while the high prevalence of pipe facets, named individuals and large quantities of parish records make the site ideal for socially historic studies.

Downloadable documents

XLSX: 39.0 KB

This downloadable MS Excel file contains photographs of the human remains excavated from the St Benet Sherehog's burial ground.

XLSX: 11.2 KB

This downloadable MS Excel file contains all data of the human remains from the St Benet Sherehog's burial ground.

Site reference

Miles, A, White, W, with Tankard, D (eds). 2011. Burial at the site of the parish church of St Benet Sherehog before and after the Great Fire: excavations at 1 Poultry, City of London. London: MoLA Monograph Series 39.

Site location

1 Poultry, 1-19 Poultry, 2-38 Queen Victoria Street, 3-9, 35-40 Bucklersbury, Pancras Lane, Sise Lane, EC2, EC4

Sitecode: ONE94

Last updated: 2025

More post-medieval sites

-

All Saints, Chelsea Old Church churchyard

Findings from the excavations after Blitz bombings uncovered 198 individuals from the 18th–19th centuries

-

Queen's Chapel of the Savoy

These human remains provide insights into the health of Londoners between the 16th and mid-19th centuries

-

St Pancras Burial Ground

Analysis of the human remains excavated during the construction of St Pancras International station

-

St Thomas' Hospital cemetery

Findings from the excavations carried out on the site of New London Bridge House, Southwark, in 1991