Who were the River Thames lightermen?

A feature of the working river for centuries, lightermen rowed through the Thames’ crowded waters to unload cargo from ships onto ‘lighters’ and take it to shore. They played a vital role in the efficiency and success of London’s port.

River Thames

Until the 1960s

Out on the river come rain or shine

When London was one of the largest ports in the world, lightermen played a vital role in keeping the city’s economy steaming along.

The name ‘lightermen’ comes from how they’d ‘lighten’ a ship, transferring its cargo into smaller boats, known as ‘lighters’.

Coal, timber, grains, fresh food – you name it, lightermen transported it, moving the goods along the river and its docks to be processed and stored. And they did so every day of the week, through storms, wind and fog.

This highly skilled job demanded a deep knowledge of the River Thames. Lightermen trained for years to understand the river’s tides, wharfs, docks and course.

They were a feature of London until the 1960s, when the new age of container shipping and mechanised cargo handling pushed the docks further out into the Thames estuary. This put the city’s lightermen out of business.

What did lightermen do?

Before London’s docks were built in the early 1800s, ships crowded into the stretch of river between London Bridge and Wapping to unload their cargo.

With only a few wharves in central London where ships could moor, lightermen did the crucial work of unloading cargo from ships anchored in the river. They’d travel over in their boats, pick up the cargo, then transfer the goods either onto another vessel or to shore. Lightermen did the opposite too, carrying goods out from shore to be loaded onto a ship.

Lightermen trained as apprentices for several years to gain a deep knowledge of the river. They knew exactly how to use the tides to move their lighters through the busy and dangerous waters.

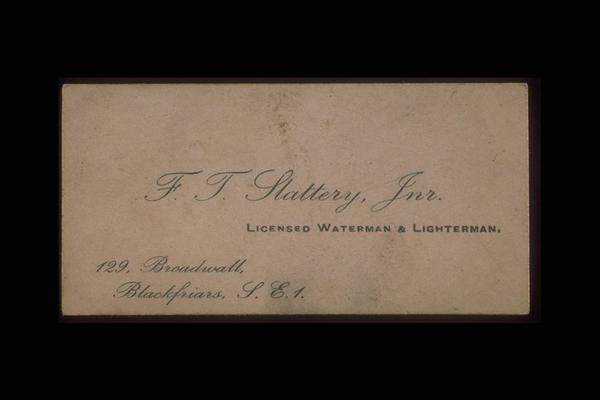

Lightermen shared the river with the equally skilled watermen, who moved people rather than goods. In 1700, lightermen joined the Company of Watermen to make the Company of Watermen and Lightermen. This guild regulated the trade and licensed trained lightermen to work on the water.

What boats did lightermen use?

Lightermen used flat-bottomed barges called lighters. These boats didn’t have motors, so they were manoeuvred by long oars. When steam power arrived on the river in the 19th century, lighters could also be pulled along by steam tugs.

Lightermen modified their boats for the kind of goods they transported. The journalist Henry Mayhew reported in 1851 how lighters would usually carry the same cargo: “a corn lighter being seldom used, for instance, to carry sugar”.

Mayhew also noted that some lightermen owned their own boats, and these were a “prosperous class compared with the poor watermen”.

London’s docks and the ‘free water clause’

In the 1700s, London became an increasingly busy port as the British empire expanded and global trade boomed. The river was clogged with ships waiting for their cargo to be unloaded and processed through customs.

Ships were vulnerable to theft, and as the process was so slow, goods could rot before lightermen were able to reach and unload them.

The solution? To build docks – enormous enclosed, secure areas which allow ships to unload their goods directly onto wharves, away from the congested chaos of the river. The proposals to build London’s first docks started to take shape in the 1790s.

Tatton Mather paints lightermen at work and a timber raft floating in Surrey Commercial Docks, 1881.

But the lightermen objected furiously. New dock complexes threatened to exclude them and significantly dent their trade.

The government responded by making a ‘free water clause’ part of the legal requirement for creating a dock. This guaranteed members of the Company of Watermen and Lightermen free access to the new docks.

But it also meant ships moored in the docks could use lighters to transfer their goods to cheaper warehouses elsewhere in London’s port. The docks took a financial hit – but not the lightermen.

“It was a way of life to be perfectly honest, a beautiful life”

Robert ‘Old Bob’ Prentice, 2012

What was life as a lighterman like?

Being a lighterman was something passed down through the generations. And as with watermen, many of these lightermen families lived close to the Thames. The long and varied working hours meant that the lighterage industry became a family of its own.

“It was a way of life to be perfectly honest, a beautiful life,” recalled former lighterman Robert ‘Old Bob’ Prentice in an interview with Spitalfields Life. “The amount of different work you did, you might start at six in the morning at West India Dock and finish at 10 o’clock at night at Tilbury. You mixed with lighterage all day long and you went socialising. It was a great fraternity.”

It was a dangerous job

At the top of this Company of Watermen and Lightermen badge in our collection is the guild’s motto: “at command of our superiors”. “And this was the wind and tide,” said one Thames lighterman. “They were the bosses.”

Company of Watermen and Lightermen livery badge, made around 1890.

The weather was a cruel dictator. In torrid wind or rain, when decks became slippery, lightermen could be washed overboard. If you did fall in the Thames and survive, you’d be taken to hospital because of all the sewage and industrial waste once pumped into it.

Harry Harris, a lighterman in the late 1800s and early 1900s, recalled that fog was “the worst enemy of river work”. During foggy or smoggy weather, caused by coal burned in the city, he said the river “became a black area. The ears became eyes, and all senses alert to get a bearing”.

Then there were the dangers of the work itself. Ships could hit lighters among the chaos of the river – especially at night. Lightermen were also sometimes hurt or killed by falling cargo while unloading.

What happened to lightermen in the 20th century?

Lightermen were a feature of the working Thames until the 1960s, when the arrival of container shipping caused their trade to nosedive.

These new container ships were huge – far too big to fit in most of London’s docks, and far too deep to navigate the Thames’ shallow waters. Even if they could make it upriver, the docks didn’t have the facilities to process their vast stacks of containers.

Ships landed further east at Tilbury in Essex instead, and all of London’s docks and wharves upriver began to lose their business. By 1981, all of the historic docks between St Katharine’s in Wapping and the Royal Docks in Newham had closed.

The lightermen – as well as stevedores, tally clerks and thousands of other skilled dock workers – lost their business. Some lightermen took on tough, lower-paid work as dockers. Others went on to work on the city’s pleasure boats, or the Woolwich Ferry.

Today, some lighterage companies still exist, transporting barges of waste, or ‘rough goods’, along the Thames to be incinerated downriver.