Ottobah Cugoano: A powerful critic of slavery

Ottobah Cugoano’s anti-slavery book drew on his own experiences of being trafficked from Africa into enslavement in the Caribbean. His progressive ideas made him one of the most powerful abolitionist voices in 18th-century London.

Queen Street, Mayfair

1750s – unknown

Writing an end to slavery

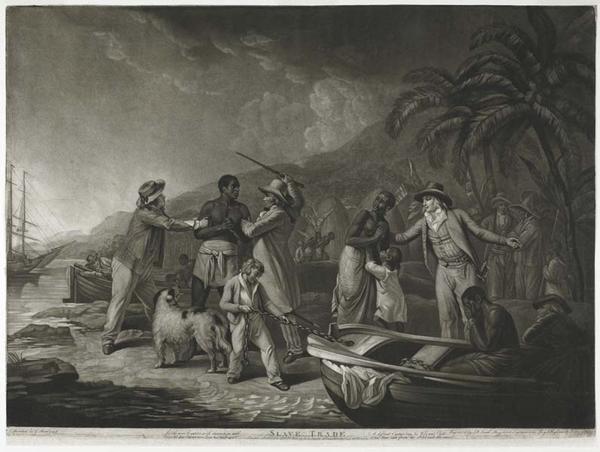

In the 18th century, a small number of the many African people trafficked into slavery were taken to London. In their efforts to abolish slavery, some began to print accounts of their own horrendous experiences of the voyage from Africa and the plantations where they were forced to work.

Ottobah Cugoano was one of the first to do this. And his arguments went further than any other abolitionist had.

In his book, published in 1787, he called for an immediate end to the “infernal traffic” in enslaved African people, freedom for the enslaved, and punishment for those who’d kept or traded African people.

Campaigners like Cugoano made the evil reality of slavery far harder for politicians and the public to ignore. Together with the resistance of enslaved people, their work gradually forced the UK’s abolition of the slave trade in 1806 and of slavery in 1833.

“that they who ought to be considered as the most learned and civilized people in the world, that they should carry on a traffic of the most barbarous cruelty?”

Ottobah Cugoano, 1787

Where was Ottobah Cugoano from?

Cugoano was born in what is now Ghana in West Africa. When he was 13 years old, he was kidnapped by African slave traders who sold him to Europeans.

They took him to Grenada, an island in the Caribbean, where he was put to work on sugar plantations. In 1772, Cugoano was sold to a new owner who brought him to England.

Although most enslaved African people were trafficked to the Americas and the Caribbean, the captains of slaving ships sometimes brought people to England. The traders sold these African people to rich families, who kept them as servants. Having a Black person as a servant became a fashionable sign of wealth for British families.

Cugoano gained freedom in London

Enslavement was legal in the Caribbean and America. But in England, the picture was less clear.

Enslaved people often escaped their masters in Britain. In 1772, a judge decided it was illegal for James Somerset, a man who’d escaped enslavement, to be recaptured and transported to the British colonies.

Cugoano arrived in England in the same year as this case. We don’t know exactly how he gained his freedom, but the Somerset case could have encouraged him.

Life as a free man in London

In August 1773, Cugoano was baptised under the name John Stuart at St James’ Church in Piccadilly, London.

Cugoano found work as a servant to the artists Richard and Maria Cosway, who lived on Pall Mall in St James’. The only image we have of Cugoano is an etching dated to 1784, which shows him serving grapes to the Cosways.

While he was a servant, Cugoano “fought to get all the intelligence [he] could” and learned to read and write.

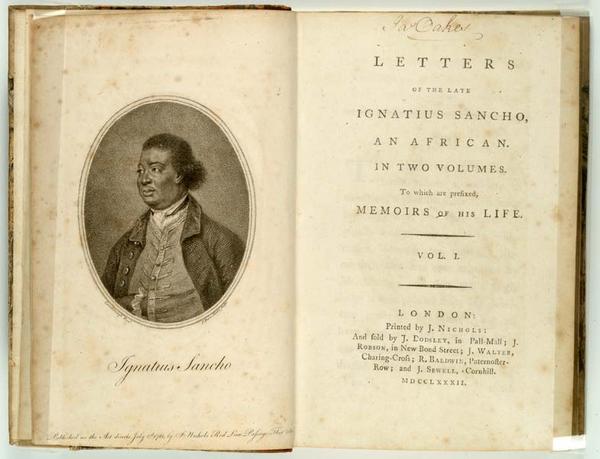

Cugoano became friends with Olaudah Equiano, another African man who’d gained his freedom. He and Equiano were founding members of the Sons of Africa, a group of men who’d all either been enslaved themselves, or were descendants of enslaved Africans. Together they wrote letters to British newspapers and spoke publicly against slavery.

Cugoano’s book describes the terror of being enslaved

In 1787, Cugoano published a book, written with the help of Olaudah Equiano, called Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species. We have a French copy of the book in our collection which was published in Paris in 1788.

The original was one of the first anti-slavery books written in English by an African person. Copies were given to powerful people, including King George III, although there’s no evidence he read it.

Cugoano describes his traumatic journey across the Atlantic. He recalls how the African people held captive came to think that “death was more preferable than life” and attempted to sink the ship.

The book also describes “the hard-hearted overseers” on the sugar plantation, who had “neither regard to the laws of God, nor the life of their fellow-men”. For eating the sugar cane, the enslaved workers were “cruelly lashed or struck over the face to knock their teeth out”. Others had their teeth removed to deter others from eating the cane.

Cugoano wanted an immediate end to slavery

The book goes on to argue that slavery and the slave trade should be abolished. He counters many of the common ways people tried to defend it, including that enslaved African people had better lives than poor Europeans.

Cugoano says that enslaved Africans had a moral duty to fight for freedom. He argued that slave owners should be punished. And that after abolition, a fleet should sail to Africa to deter slave traders.

The last point soon became reality – after the trade in enslaved people was abolished in the UK in 1807, the Royal Navy sent ships to patrol the West African coast.

Cugoano’s book judged “every man in Great-Britain responsible, in some degree” for slavery “unless he speedily riseth up… and, to avert evil, declare himself against it”.

He also highlighted the hypocrisy of the English. “Is it not strange to think, that they who ought to be considered as the most learned and civilized people in the world, that they should carry on a traffic of the most barbarous cruelty and injustice, and that many... are become so dissolute as to think slavery, robbery and murder no crime?”

Cugoano later moved to Grosvenor Square.

What else do we know about Cugoano?

In 1791, we know Cugoano was living at 12 Queen Street, Grosvenor Square, in Mayfair. Today, there’s a blue plaque there.

In 1791, Cugoano announced that he wanted to open a school for Africans in Britain. We don’t know if he ever did this.

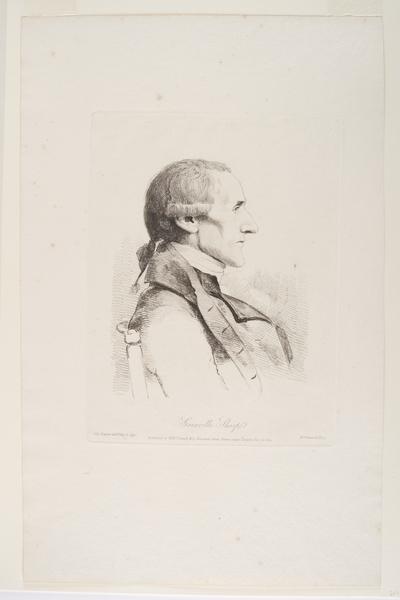

In the same year, he wrote to Granville Sharp, a fellow abolitionist. In the letter, Cugoano says he wanted to go to Nova Scotia in Canada. There, he aimed to recruit free Africans to develop a settlement in Sierra Leone in West Africa. We have no evidence that he ever went.

After that point, we know nothing about Cugoano’s life. The date of his death is unknown.