‘Munitionettes’ & women’s football in the First World War

The women’s game hit the big time during the First World War (1914–1918). As women were recruited into the workforce, they were encouraged to pick up football to boost camaraderie, keep fit and raise crucial funds for wartime charities.

Across London

1914–1918

Levelling the playing field

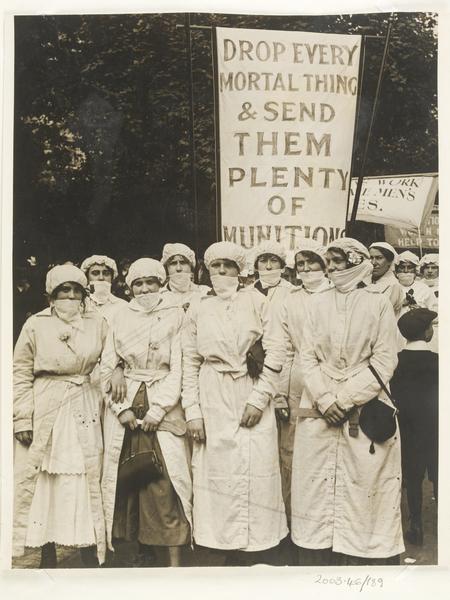

Women were brought into the British workforce in huge numbers during the First World War. Many worked in munitions factories producing military items like bullets, explosives and weapons. To build their morale and increase productivity, the ‘munitionettes’ were encouraged to play organised sports.

Women’s football had been steadily gaining momentum since the 1890s, but it became the game of choice during wartime. Women from across the workforce started football teams and competed with each other.

Despite being a popular and growing spectator sport, the final whistle was blown on women’s football shortly after the war. Men who’d been on the battlefields returned to the workforce and, all of a sudden, the sport was judged to be inappropriate for women.

The Football Association (FA), the sport’s governing body in England, banned women’s football in 1921. It crushed the growth of the game for almost 50 years.

The First World War accelerated women’s entry into the workforce

Women had been working in industry before 1914. When war broke out, many of the factories they worked in, like those manufacturing toys, were converted to produce munitions.

Across Britain, over a million men had volunteered to fight by the end of 1914. And in 1916, conscription was introduced, meaning all fit men aged between 18 and 41 were ‘called up’ to fight on the front line. Factory bosses turned to women to fill their roles.

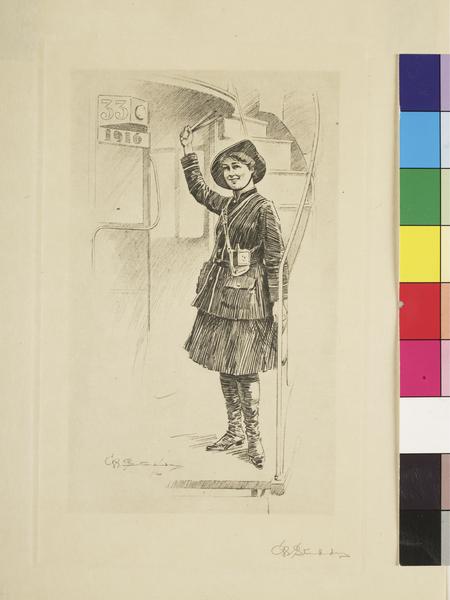

Almost one million women worked in munitions by 1918, while others joined service industries like transport, the postal service and the police. Pay in the factories was about half of what men were getting. But many munitionettes found greater independence and a sense of comradeship in the experience of working together for the war effort.

Wartime factory work was dangerous

Munitionettes worked long hours in dangerous conditions. They didn’t have good protective clothing and were exposed to toxic chemicals that could affect the liver or cause yellowing of the skin. Munitionettes were often called ‘Canary Girls’ because of this.

There was also a risk of death. Over 200 women were killed by explosions or poisoning while doing munitions work. In 1917, a fire at a TNT refinery in Silvertown, Newham, caused a huge explosion that killed 73 people and injured 400 more. The same year, a blast at the Ajax Chemical Works in Barking killed 13 women workers.

The Silvertown explosion, seen from a silo granary at Royal Victoria Dock.

Women workers played sport for fitness and morale

The government sent welfare supervisors to the factories to check on the wellbeing – and therefore, the productivity – of factory workers.

Aside from the tough working conditions, women were losing brothers, fathers, friends and loved ones at war. To help morale, bosses encouraged their employees to carry on the tradition of male workers playing team sports, like football and cricket.

Many of London’s oldest professional football clubs, such as West Ham and Arsenal, began life as factory workers’ teams.

“my girls at Woolwich were keen as mustard on gymnasium, swimming and football”

Ministry of Munitions official

In 1918, an official from the Ministry of Munitions told the Daily Mirror: “drill, music, dancing, games are what our munition girls need to make them efficient. After twelve hours’ work and an hour’s travel to and from home my girls at Woolwich were keen as mustard on gymnasium, swimming and football, and it made them the fine workers they are.”

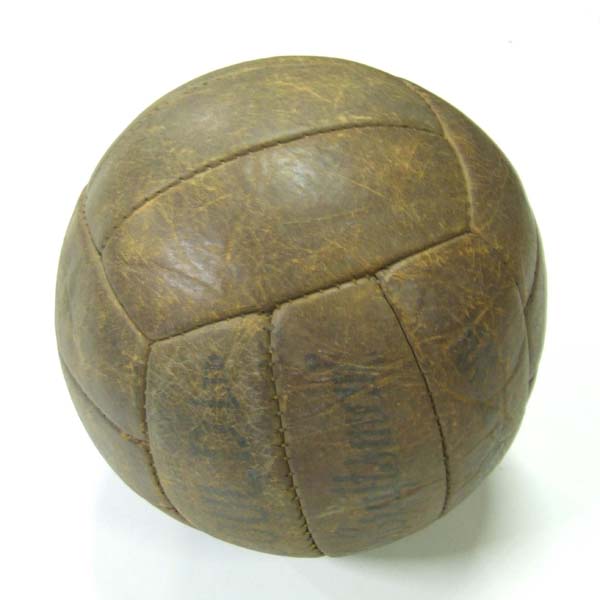

For the munitionettes and other wartime factory workers, football came out on top. Almost every factory in Britain involved in war work had a ladies' football team, who’d play on their lunch break or after gruelling long shifts.

While many played against other company departments, some teams travelled across the country to play each other. Football’s popularity extended to women working in service industries. Even the department store Harrods and Lyons’ tea houses had their own teams.

Football played a part in the war effort

The FA encouraged the women’s games from the get-go. Matches raised much-needed funds for wounded soldiers and their families, so the organisation embraced their patriotic spirit.

Women’s football also became a very popular spectator sport, with some games drawing tens of thousands of fans. Increasingly, match reports were featured in local and national newspapers. The tone of these articles shifted away from the criticisms of women’s football seen in the late 1800s.

The popularity of women’s football continued after the war. By 1921, there were at least 150 women’s football clubs. The beautiful game was on the up.

Britain’s star teams

Football was particularly big in the north of England, the home of the Munitionette’s Cup competition. The Dick, Kerr factory in Preston, Lancashire, produced one of the country’s most famous wartime women’s teams. They won 746 out of their 800 games.

While the Dick, Kerr Ladies FC dominated up north, Sterling Ladies FC were the stars of the south. The team worked for Sterling Telephone & Electric Co. in Dagenham, an electrical equipment manufacturer which was mobilised to make munitions parts during the war.

Sterling Ladies Football Club, aka, the 'Dagenham Invincibles'.

Sterling were known as the ‘Dagenham Invincibles’. They never lost a match in their 36-game career. Sterling’s rampages in their blue-and-white kit were reported in national newspapers, including those against London teams like Harrods.

Why was women’s football banned in 1921?

Despite the game’s increasing popularity, attitudes towards women’s work and sport went backwards after the war.

Men from the front line returned to the workforce. Many factories that had been mobilised returned to their pre-war role. Women were forced to return to a more traditional domestic role, or find work in less physically demanding industries, like retail.

It didn’t matter that women had just spent four years doing the same dangerous jobs as their male counterparts. Football was seen as a threat to women’s health, just as it was in the late 1800s.

“the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged”

The FA, 1921

The Arsenal manager at the time, Leslie Knighton, pointed to the injuries of men footballers and said: “should [women] get similar knocks and buffetings, their future duties as mothers would be seriously impaired.”

One doctor on Harley Street, the Marylebone road famous for medical services, called football “the most unsuitable game, too much for a woman’s physical frame”.

On 5 December 1921, the FA announced a ban on women’s football being played at professional grounds and pitches of FA-linked clubs. The FA ruled: “the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged.”

The ban lasted until 1969, halting the game’s growth for almost 50 years. Until then, women’s football – a joy for women up and down the country, and a true spectator sport – was sidelined to parks and fields.