The Battle of Barnet: North London’s bloodiest morning

In 1471, the Wars of the Roses made Barnet a battlefield. In one of the conflict’s major clashes, King Edward IV defeated and killed Richard Neville, the ‘kingmaker’ who’d betrayed him.

Hadley Green, Barnet

14 April 1471

A thousand fall in the fog

During the Wars of the Roses (1455–1485), two sides of the royal family – the houses of York and Lancaster – competed for the English throne. It took 30 years before the Yorkists and Lancastrians made peace.

One of the final battles took place close to Barnet, then a village beyond London’s boundaries, but now part of north London.

Thousands of soldiers fought hand-to-hand. Cannons boomed and arrows rained down in the morning fog. It’s thought around 1,000 men, possibly more, died.

When the killing was done, the Yorkists, led by King Edward IV, had triumphed over the Lancastrians, led by Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick. Neville was killed as he fled.

The Wars of the Roses, 1455–1485

Over 30 years, the House of York and the House of Lancaster fought each other in a dispute over who should rule England.

Centuries later, the conflict was named the Wars of the Roses. This referenced the white rose emblem of York and the red rose of Lancaster.

During the Wars of the Roses, noble families and their supporters wore badges of their emblems to show their allegiance.

After a series of battles across the country, the conflict drew to a close in 1485, with the Lancastrian Henry Tudor taking victory. He became the first Tudor king of England, ruling as Henry VII.

Henry married Elizabeth of York to unite the warring families. He created a new emblem of unity, a hybrid of the white rose badge of York and the red rose of Lancaster.

How were the Wars of the Roses fought?

Wealthy, powerful families led private armies to war, deploying skilled European mercenaries and paid British men with a range of experience.

Noblemen, or knights, fought in heavy metal plate armour, mostly on foot. Regular soldiers wore some combination of chainmail, padded jackets and metal plate.

Archers fired their bows from a distance. Cannons and early hand-guns were also used. But for soldiers wielding close-combat weapons, like polearms and swords, the fighting was personal and brutal.

Some clashes in the Wars of the Roses were extremely deadly. Estimates from the time of the 1461 Battle of Towton in Yorkshire put the death toll at 28,000, although that’s likely to be an exaggeration.

But the conflict was sporadic and localised, rather than an all-consuming civil war. There were fewer than 15 months of actual fighting over the 30 years.

Who was involved in the Battle of Barnet in 1471?

The Yorkist forces were led by Edward IV. The Lancastrian army was led by Richard Neville, the extremely powerful, extremely wealthy earl of Warwick.

Neville was Edward’s cousin. He’d helped Edward take the throne from the Lancastrian King Henry VI in 1461, and became one of his key advisers and supporters.

But in 1470, Neville betrayed Edward. He switched allegiances back to Henry VI and helped the former king regain the throne. Edward was forced into exile in Europe.

Neville is known as the ‘kingmaker’ for his influence in winning the throne for Edward, then replacing him with Henry.

Other noblemen also fought at Barnet. This included Richard, Duke of Gloucester, a Yorkist. He later became King Richard III.

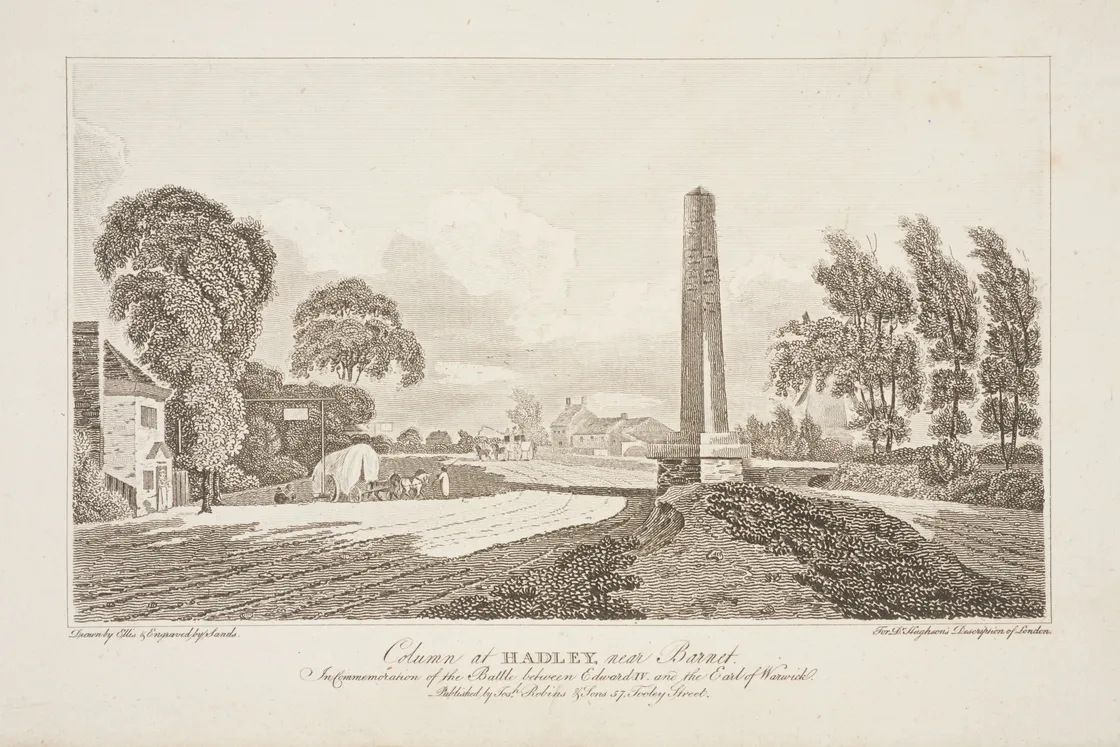

A column said to mark the site of the battle, erected in 1740.

Why was the battle at Barnet?

Edward IV returned from his exile in March 1471 and landed in Yorkshire, where he gathered an army. He rushed south, took control of London, captured Henry VI and held him in the Tower of London.

Edward then marched his troops north to meet Neville, who was leading his own force south from Coventry.

Barnet was on one of the key roads heading north from the city. The two armies met around a mile north of the village. We don’t know the exact location of the battle.

“a great myste… suffred neythar party to se othar, but for a litle space”

Historie of the arrivall of Edward IV, by an anonymous servant of King Edward IV

How did the battle unfold?

Edward IV had between 9,000 and 12,000 men. Neville’s Lancastrians outnumbered them, with 15,000 to 20,000 men.

Neville arrived in the area first, setting up camp on 13 April. Edward and his troops arrived that night, pitching up a short distance away.

A chronicle was written around the time of these events, called the Historie of the arrivall of Edward IV. It tells us that Neville’s forces “shotte gunes almoste all the nyght”, but missed their target.

On the morning of 14 April, Easter Sunday, Edward staged a dawn attack. His troops advanced in a heavy fog, “a great myste” that “suffred neythar party to se othar, but for a litle space”.

It was a chaotic fight. At one point, some of the Lancastrians accidentally attacked their own men, who then fled fearing that their allies had turned on them. Mid-battle betrayals did sometimes happen in the War of the Roses.

Edward’s Yorkist army overcame Neville’s Lancastrians, who turned and fled. Significantly, Neville was killed as his soldiers retreated. By 10am, it’s thought around 1,000 men – but possibly as many as 3,000 – had been killed.

London’s defenders charge out of a city gate in this scene from the Historie of the arrivall of Edward IV.

A siege on London

The chronicle tells us that the Edward IV rested at Barnet, then “returned to his Citie of London, where into he was welcomyd and receyvyd with moche joy and gladnesse”.

But the king was soon on the warpath again, winning the Battle of Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire a month later.

While he was gone, the war came to London. From 12–15 May 1471, the city was attacked by a Lancastrian army attempting to rescue Henry VI, who was still being held prisoner in the Tower of London. A pilgrim badge from our collection shows him standing on the battlements.

The chronicle describes how soldiers approached Aldgate and Bishopsgate, where “they shot goonns and arrows into the citie, and dyd moche harme and hurte”. They also tried to set fire to London Bridge. London’s citizens gathered in defence and, helped by an approaching Yorkist army, they dispersed the attackers.

Edward returned to London on 21 May. Henry died in the Tower the same day. We don’t know exactly how he died, but it’s likely that Edward had him killed to secure the throne. Edward ruled for the rest of his life, until 1483.