10 February 2026 — By Chery Nguyen

Celebrating Tet, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year in London

A significant part of Vietnamese culture, Chery Nguyen shares what celebrating Lunar New Year meant to her as a child, and now as a teacher and mother.

My mother would line us up by the door in height order, looking very cute and dressed our absolute best. When our aunties and uncles arrived, we’d welcome them saying, “Chuc mung nam moi!” (I'm wishing you a Happy New Year!)

What followed was a day of pure fun. Laughter bouncing off the walls, cousins catching up, plates piled high with incredible food. And the best part for us kids – Li Xi, the lucky money tucked into red envelopes. This tradition, where adults give money to children and family, symbolises good luck, health and prosperity for the coming year.

“Celebrating Lunar New Year gives me a sense of achievement, of being seen and accepted”

When Tet came to south London

Tet Nguyen Dan, or Lunar New Year, is the biggest celebration for Vietnamese people. It marks the first day of the luni-solar calendar, which is why the date shifts each year – usually falling in late January or early February. It’s been called Chinese New Year, but Vietnamese celebrations have their own unique traditions. This includes the square Banh Chung and cylindrical Banh Tet steamed rice cakes, which must be offered to ancestors before anyone else can touch them.

Growing up in south London during the 1990s, I knew Tet was coming when my mother, Lai, started the serious cleaning, about a week out. Our home would transform with vibrant reds and golds, a striking contrast against the grey skies outside.

Standing out while fitting in

My three siblings and I didn’t see many Asian families around us, whether at school or in our neighbourhood. Western culture surrounded us, and sometimes we had to push our heritage into the background to fit in. That made celebrating Tet at home even more important. It was our connection to who we were.

I remember going to the temple as a kid. A trip to See Woo on Lisle Street in Chinatown was like a special event in itself. This Asian supermarket opened in the mid-1970s, during the influx of Vietnamese refugees to the UK around the end of the Vietnam War (1955–1975). It was a landmark for the Southeast Asian community. My parents arrived from Vietnam around that same time.

Looking back now, I realise how bold they were to maintain these traditions so far from home. My mother especially kept things traditional, spending days preparing for a feast that would feed family and friends from across London.

The preparation

My mother made moon cakes from scratch – those dense, sweet Chinese pastries with lotus seed or red bean paste filling. She used a yellow construction tube (“it was the best rolling pin ever”, she’d insist) to spread the pastry dough. She still keeps it in a plastic shopping bag – the kind you’ll find in most Vietnamese homes, mine included.

The morning of Tet, huge pots would clang in the kitchen. The cleaver would thud against the cutting board. Savoury sticky rice cakes steamed for nine hours while pho broth simmered away, the smells mixing together and filling every corner of our house.

Preparing the steamed rice cake, Banh Chung, 2025.

By the time guests arrived, the table practically groaned under the weight of it all – lobsters, fish, duck, stir-fried vegetables, my favourite Nom (Vietnamese coleslaw). But none of it could be had until the food was blessed. Else bad luck would follow, my mum always warned.

Gratitude and blessings

A huge part of Tet is making offerings to our ancestors and asking for their blessings. We’d pray for luck, prosperity and good health, burning incense and Hang Ma (paper money offerings) at the altar and in the back garden. The incense smell was so strong, it wove itself into the rice aroma.

Decades later, that specific combination of smells still hits me with vivid memories and a deep sense of belonging. That’s what I want to pass on to my daughter Ponyo and my students, especially since we don’t have any photos of the time to remember them by.

Chery’s daughter Ponyo and mum Lai Nguyen during Tet in 2025.

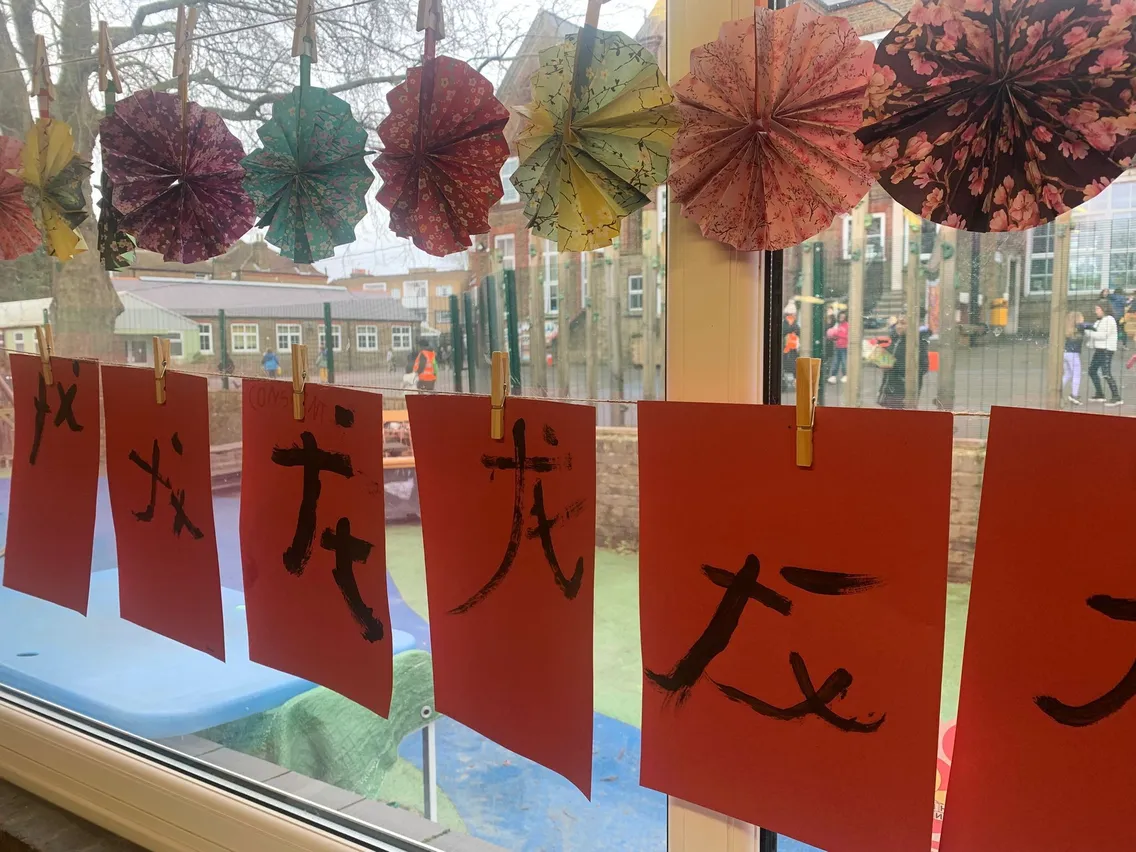

Bringing Tet into a multicultural classroom

As a teacher and my school’s head of Religious Education, I now share these rituals with my Early Years students. Lunar New Year sits alongside Diwali, Eid and Christmas in our curriculum. The classroom itself is more diverse than my 1990s school ever was, which means more cultural exchange, and more understanding.

We make traditional hats, Trong Boi pellet drums and red envelopes for lucky money. I teach the kids how to fold dumplings the way my mother taught me. We practice greetings in Vietnamese. They love hearing the legend of Tet – the story of the Jade King who organised a race to decide which animals would have a year named after them. That’s what gives us the year of the rat, cat, ox or as this year – horse.

“The biggest difference between my childhood and now is visibility and acceptance”

But the biggest difference between my childhood and now is visibility and acceptance. Vietnamese food exploded in popularity during the 2000s, especially in east London, where Kingsland Road earned the nickname, Pho Mile. Our parents built these businesses from the ground up. Popular shows like celebrity chef Luke Nguyen's UK put Vietnamese culture in the spotlight. The younger generation, irrespective of their heritage, knows who we are.

A new generation, similar traditions

This is the world my daughter’s growing up in. At Tet, we still go to my mother’s house, where she loads the table with the same dishes I grew up with. My daughter dives into the food with the same enthusiasm I had, especially the sticky rice.

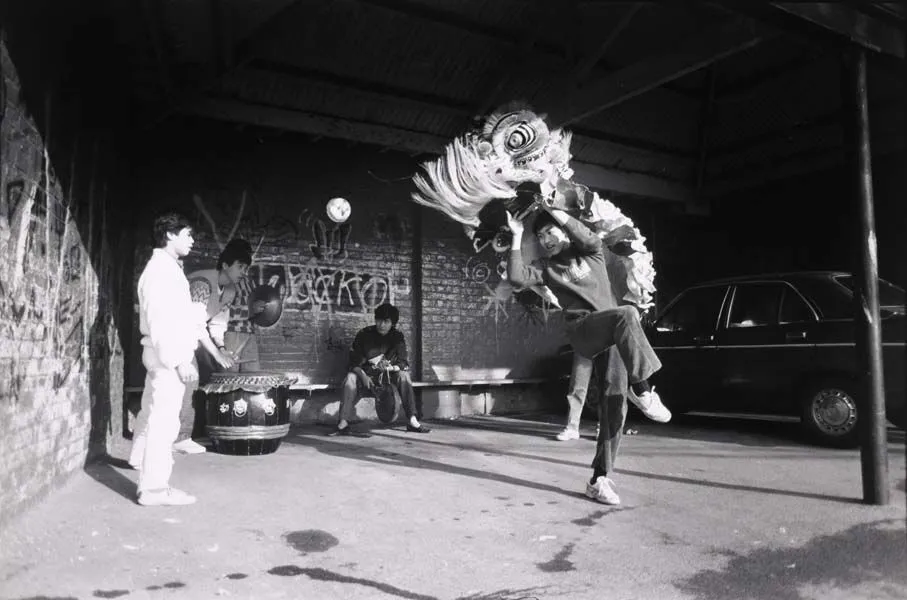

But now there’s something I didn’t have – public celebration. I would take her to Deptford Lounge, where hundreds gather for a huge Tet festival. She’d often wear her Ao Dai, the traditional Vietnamese long-sleeved tunic worn over trousers, and play with other Vietnamese kids. Their laughter mixing with the thunderous drums of the lion dances.

Watching her, I see what’s changed. She doesn’t have to choose between her heritage and fitting in. She gets to be fully Vietnamese and fully British, in a city that now celebrates both.

My mother still makes those moon cakes with the construction tube rolling pin. I haven't made them myself yet, but I plan to – probably with a twist. The incense still burns at the altar. The traditions continue, passed from her hands to mine to my daughter’s, evolving with each generation while keeping their essence intact.

For me, the widespread public celebration of Lunar New Year is about more than tradition. It’s a sense of belonging and pride. It gives me a sense of achievement – of being seen, being accepted and, most importantly, being celebrated.

Chery Nguyen is an Early Years teacher and illustrator with a passion for nurturing creativity in young children. She facilitates artistic workshops that open opportunities for learning, exploration and creative skill development.

Join Chery for a drum-making workshop at London Museum Docklands on 21–22 February.

As told to Shruti Chakraborty, Digital Editor (Content) at London Museum.